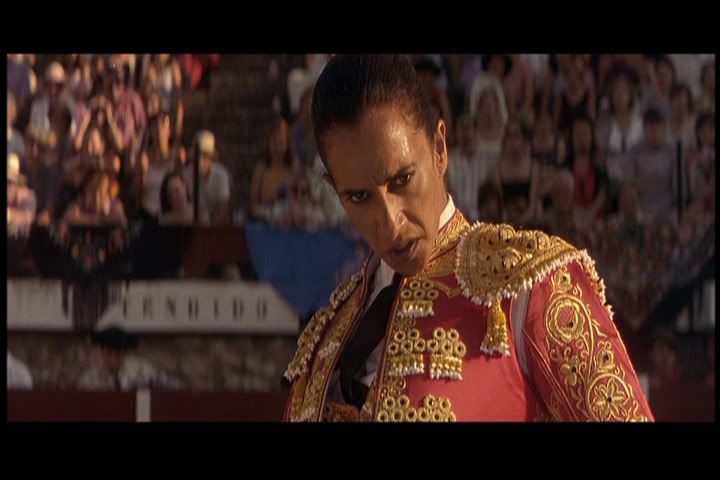

Pedro Almodóvar's Talk To Her delicately handles some potentially very creepy and bizarre subject matter in order to create some genuine sympathy for its pair of unlikely heroes. The story focuses around Benigno (Javier Cámara), a hospital orderly who is obsessed with the ballet dancer Alicia (Leonor Watling), who practices at the studio across the street from his apartment. When Alicia gets in a car accident and goes into a deep coma, Benigno becomes her private nurse at the hospital, caring for her with a personal touch, talking to her, massaging and bathing her daily, and continuing to indulge his unhealthy obsession for her. Meanwhile, Almodóvar weaves in the initially separate story of Marco (Dario Grandinetti), a reporter who falls in love with his latest subject, the bullfighter Lydia (Rosario Flores). The two stories converge when Lydia too succumbs to a coma, after a fight in which she is gored by a bull.

This is a complex film, an examination of love, loneliness, and the power of memory and imagination in bridging that gap, told from a specifically masculine viewpoint. It's a film about the formation of couples, a fact that Almodóvar announces by shooting a title on-screen with the couple's names every time a new pairing forms. Benigno and Marco are both somewhat scarred characters, haunted by their pasts and the emotions they still carry with them. Benigno is a sheltered and sexually ambiguous virgin who spent the bulk of his life caring for his ailing and apparently domineering mother until she passed away. Everyone around him thinks he's gay — one of the reasons he's allowed to care for Alicia so intimately — but more than anything he simply seems naive, unaware of what the realities of sex and relationships are like for most people. Marco is equally scarred, by the specter of his last relationship, with a volatile and beautiful blonde who continues to haunt him ten years after their break-up. It's only with Lydia that he finally begins to forget, and then she too is taken from him.

Almodóvar shows great care in examining the depths of both men's feelings, an especially delicate operation since Benigno winds up being a potentially very unlikeable character. But despite his actions later in the film, he remains sympathetic and entirely understandable; more sad than reprehensible. He is clearly a man damaged by his mother, with something of an incomplete view of life. His reverential and confused feelings for Alicia are best summed up by a scene in which he describes to her a silent film that he recently saw. As he narrates the film's plots, Almodóvar shows scenes from the film, which is of course invented for the occasion. It concerns a man who loves a scientist who is somewhat indifferent to him. To prove his love, he consumes her latest invention, a diet formula which unexpectedly makes him shrink, eventually down to very tiny size. The final scene which Almodóvar shows is the man watching over his now much larger love while she sleeps; he pulls away the covers, climbs all over her mountainous naked breasts and down the valley of her stomach, and finally to between her legs, where he strips and climbs inside of her.

It's a remarkable scene, and Almodóvar milks it for equal parts pathos and kitsch. The black and white, slightly sped-up presentation of the silent film clearly gives the scene a comedic vibe, as does the patently rubbery appearance of the poor special effect used to achieve this lurid fantasy — doubtless an intentional gesture to the days when effects were plastic rather than computer-generated. But the scene contains poignant echoes of Benigno's own emotional fixation on his helplessly sleeping Alicia, who he elevates to tremendous proportions, and whose body he also explores while she sleeps. The silent film also provides a mirror of Benigno's dead and overbearing mother, both in the film's evil mother character, from whom the heroine rescues the tiny man, and in the potent image of a return to the womb. One of Almodóvar's greatest gifts is this ability to play a scene both for laughs and the deeper, often uncomfortable layers of emotional meanings beneath the laughs. This scene is both deliriously, ridiculously silly, and painfully raw in the way it lays bare the inner workings of Benigno's emotional life. And that's as good a summary as any of the film as a whole, as well. Marco's story is more understated than Benigno's, both less funny and less gut-wrenching, and he winds up as the younger man's stable friend and confidant. But even in Marco's much quieter storyline, there's room for another brilliant and beautiful scene, as Marco remembers an incident from his long-gone relationship and, sure enough, the scene materializes in the air around his head, a hazy vision of a long-ago night on the African plains. It's a gorgeous and affecting scene, with the shadowy image of this memory floating in the very air around Marco, like smoke exhaled from his mind. The film as a whole retains that feeling, with different emotions mingling together like tendrils of smoke: sadness, nostalgia, love, desire, loneliness, and sensuality.

Vincent and Theo is a biography of Vincent Van Gogh and his brother Theo that largely ignores the great painter's artworks in order to focus on the man, his conflicts, and his relationships. Director Robert Altman is of course a perfect helmsman for such an idiosyncratic approach to an artist's life, with his preference for ragged technical qualities and a loose, flowing style that's much closer to life than the glossy schematicism of most Hollywood film. Altman chose to focus in on Van Gogh's tortured and even parasitic relationship with his brother Theo, an art dealer who always supported Vincent even though his paintings never made a penny during either of their lifetimes. The film is a subtle commentary on the transience of art and artistic values, of the influence of commerce on art, of the shifts in value which define the difference between a masterpiece and a piece of trash. The film opens with a modern-day auction in which the value of a Van Gogh painting for sale is escalating by the hundreds of thousands with each bid. Altman then cuts away to a shot of Vincent (Tim Roth), lying in bed with dirt on his face, as the sound from the auction continues in voiceover, with the painting's value finally ending up above £22 million. This tension between history's later estimation of artistic worth and the reality of the life that made it is at the center of the film.

To this end, Altman's trademark darting camera moves around within the Van Goghs' lives, always providing an intimate view of the artist at work which eschews glamour for grittiness and even ugliness. Roth is phenomenal here, in one of his best roles. His portrayal of Vincent has a tinge of madness, but mostly just a willingness to get down and dirty in every way — with peasant people for subjects, with his impoverished lifestyle, and with the casual way he treats his paints and materials. Two of the most striking scenes are a pair in which Vincent smears paints on his own face in his impressionistic style, and later does the same to a prostitute in a bar. It's the ultimate symbolic expression of life and art intermingling, as Vincent attempts to transform his very life, his own being, into an artwork. In another scene, Altman shows Vincent in a field of sunflowers, painting the scenery, and the camera seems to take on the artist's point of view, zooming and darting around the field, focusing on a single flower, finding the few broken and wilting buds within the seemingly lush whole, then zooming back out as though the artist's eye were moving on to something else. It's an interesting approach, a divergence from the usual technique in artists' biographies of showing the process of the art as it progresses from raw material to finished. There is very little of that in Vincent and Theo, only a few scenes with very minimal detail shown; Altman prefers to get into the thought process, the sensual experience of making art, rather than the physical nitty-gritty of what it looks like.

This is prime Altman, a perfect example of a subject that seems to have been made for his style. The film's examination of a life dedicated to art without recognition might very well be a parallel to Altman's own career, during which he was often in danger of being forgotten and his films unseen. The film stresses the transience of art, as Vincent treats his artwork often with carelessness and even contempt. He's continually throwing canvases, breaking them, or smearing them over with paint. The fact that this work survived, that Van Gogh is still remembered today, is as much due to luck as talent. This wild, messy film is as fitting a tribute as any to that wild, messy man and his wild, messy art.

Finally for today, I ended on a much lighter note with the 1940 Ernst Lubitsch comedy The Shop Around the Corner. Actually, comedy might be too strong a word, although there are certainly more than a few moments in the film that had me roaring with laughter. But overall, the film strikes more of a bittersweet, understated tone, never quite settling down for flat-out comedy but always keeping a rich, textured emotional palette in play. The story, set in a small shop in Budapest, is as simple as it gets. The store manager, Kralik (Jimmy Stewart), and the newest employee, the brash and outgoing Klara (Margaret Sullivan), clash with each other continuously, without realizing that at the same time they are carrying on an anonymous courtship with each other by way of love letters. The plot throws in the rich tapestry of the other shop employees and some work drama to complicate matters a bit, but the core narrative is relatively straightforward, and the resolution shouldn't be too surprising to anyone who's ever seen a romantic comedy before. But Lubitsch handles this material with such wit, charm, depth, and nuance, that it's virtually impossible not to be bowled over by this affecting and charming story.

It helps, of course, that the leads are great. Stewart especially is at the top of his craft, a first-class actor turning in one of his best lead turns. One of the film's themes is that everyone has many sides to them, and that we often conceal in one situation what we would exaggerate in another. Stewart's character embodies this layering of personality, with a sensitive and intelligent inner core that he often covers up with his sarcastic wit and straightforward manner. Sullivan doesn't have quite as much to do, or quite as subtle a range of emotions to traverse, but she is an apt sparring partner for Stewart's wit, and the pair crackles whenever they're on screen together. The rest of the cast is equally strong, from the hilarious wise-cracking errand boy (William Tracy) to the grandfatherly Pirovitch (Felix Bressart) to the peevish but ultimately good-hearted shop owner (Frank Morgan).

This is a warm, lovely, and unforgettable film in the classic Hollywood comedy tradition. Its style is understated, as is its story and its humor. Lubitsch has faith in these characters and the reality of this place, the comfortable confines of the little gift shop they all work in. He lets them really inhabit this space and doesn't rush the script in order to dive right into the heart of the plot. In the first half of the film, the romance takes a distant second to the banalities of work and the day-to-day existence of the working classes. The scenes of the characters all gathering outside the door, idly chatting and gossiping as they wait for the working day to begin, have a realism which belies the film's origins in the realm of glossy romantic comedies. It's only in the second half of the film that the romance storyline truly begins to develop, growing organically from the seeds already sown in the first half. It's this patience, this attention to details which fall outside the core romantic plot, that elevates Lubitsch's craft here above his peers. The film is such a delight because there's so much to it, so many layers built into its deceptively simple premise. It's an uproarious comedy, a sugary romance of opposites attracting, a wonderfully subtle look at working class life, and a parable on the multifaceted nature of humanity. It's also just a really great film.

No comments:

Post a Comment