One usually doesn't think of a stridently avant-garde filmmaker like Derek Jarman making rock music videos, but during the late 70s and 80s the British director frequently contributed to the music video form, crafting videos for the Sex Pistols and Marianne Faithful. Jarman had a particularly fruitful collaboration with the Smiths, for whom he made the charming, funny video for their single "Ask" and the multi-song miniature masterpiece The Queen Is Dead. This gorgeous 13-minute film was accompanied by three of the Smiths' songs: "The Queen Is Dead," "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out," and "Panic." The film is of a piece with the evocative collage features Jarman made during the same period, proving that this so-called "music video" is as much a part of his oeuvre as The Angelic Conversation or The Last of England.

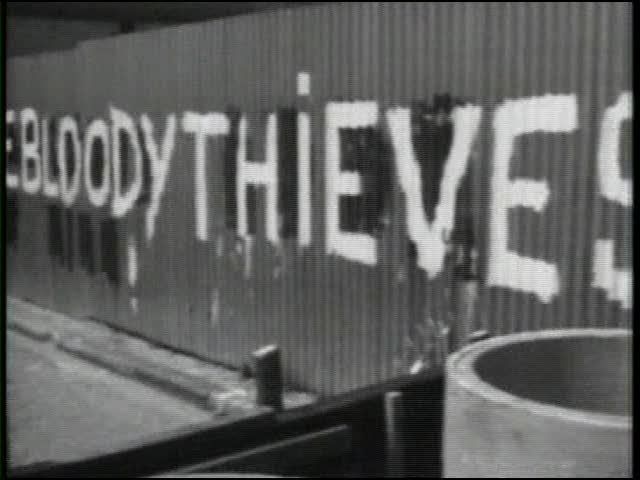

The film is structured around its trio of songs, with each part somewhat distinct from the others. The songs flow into one another, and the first and third section mirror each other in style and techniques, but the film is unmistakeably a triptych rather than a seamless whole. The film opens with Jarman's frantic, jittery interpretation of "The Queen Is Dead," with the imagery conjuring a nightmare vision of disintegrating England to match its title sentiment. In strobing, sped-up motion, hoods spray paint slogans across crumbling stone walls, a flaming record shoots across the screen like a comet, a young man with angel wings appears to be suffering, doubled over in pain, and jeweled crowns float in the midst of layered video superimpositions. This segment is unrelentingly fast-paced, matching the steady pulse of the accompanying song.

Jarman's images are simple and iconic, and he repeats them as though spelling out a mysterious coded message in rebus form: flower petals, a girl's face, a revolving guitar, abandoned buildings. Only towards the end does the repetitive structure begin to break down, opening up for several longer shots of a girl with close-cropped hair frolicking in a courtyard surrounded by desolate buildings, throwing a British flag into the wind to flutter above her. The pace slows only slightly for these shots, and there are still interjections of layered video abstractions, but the effect of this slight slackening is exaggerated by the film's overall density and speed. These few moments of relative relaxation are stunning in context.

This also sets up the film's much more deliberately paced second segment, based around one of the Smiths' finest songs, the morbidly romantic ballad "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out." The song apparently brings out the best in Jarman as well, for the images he pairs with this music must surely rank among the most beautiful, haunting few minutes in his entire oeuvre. His illustration of the song's maudlin lyrics — wishing for a romantic mutual death — is simple and direct, accomplished by layering several images on top of one another and fading between them, allowing the intersections of different film stocks and colors to create tactile, textural compositions. An androgynous young woman, bathed in deep blue light and lying on her stomach, sleeps in the midst of this collage, Jarman's camera moving sensuously across her body, letting the light play along her skin. She is deliberately positioned so that her gender is actually unclear — she might just as well be a feminine young man. This image is blended into black and white footage of two lovers kissing together in a field, a twinkling overlay of golden light, and footage of fiery wrecks and car crashes, sometimes in grainy black and white and sometimes emitting purplish flames.

The images are basic, and obviously constitute Jarman's illustrative response to the song's lyrics: "and if a ten ton truck/ kills the both of us/ to die by your side/ well, the pleasure and the privilege is mine." The film's beauty, however, lies in the way Jarman transforms this simple premise into something deeply emotional and moving, a sumptuous depiction of a love so powerful that it endures even through death. Jarman's use of superimposition, besides being visually striking, has always been a way of creating dense layers of emotion that could not possibly be contained within a single image otherwise. His layering of images rarely serves a narrative purpose, though in this particular instance the juxtaposition of the sleeping woman with the other images could easily be construed as a representation of dreams or memory or imagination. In fact, though, Jarman doesn't seem to be suggesting a story so much as creating an atmosphere, exploring the melodramatically romantic mood of the Smiths song. The young woman is sexualized by Jarman, but in a way independent of any gendered sex characteristics: the camera admiringly crawls across the naked upper torso and legs, fading in and out of the sea of images, capturing the way light and shadow play across the skin. Considered in the context of Jarman's gay sexual identity, this film might by read as an acknowledgment of the impossible array of social and political forces sabotaging the possibility of gay love, leaving death as the only viable option — and yet at the same time opening up other, more hopeful possibilities by layering in the pastoral image of the kissing lovers.

This second segment is a pivot point, a moment of sad but beautiful tranquility in the center of the film's rushing torrent of imagery. The final segment, Jarman's video for the Smiths' "Panic," returns to the jittery pacing and jumpy camerawork of the first section. He even reuses some of the same imagery — the flaming record, rope-jumping schoolgirls in negative, the crowns, a static shot of a British pound note — while the video for "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out" utilized an entirely distinct visual palette. This brief final section essentially recycles and revisits the opening, this time centering on a young man walking around a grimy black and white London but quickly cutting away to and layering in all sorts of other images. The sensory overload is no doubt intentional on Jarman's part, suggesting an apocalyptic world about to fall apart at any moment. A hand, perpetually outstretched as though begging, shakes and blurs, propelled by the insistent beat of the music.

Though short and created as a commission — Jarman himself reportedly dismissed his collaborations with the Smiths as only a paycheck — to treat The Queen Is Dead as minor Jarman would be to ignore one of the director's most concise and beautifully realized summations of his avant-garde collage work. These evocative, poetic, multi-layered images create webs of resonance with the Smiths songs they're accompanying. The result is not only the rare music video that actually enhances and emotionally intensifies the music, but one of Jarman's great films.

What a strange coincidence! I just found a couple of my old Smiths albums yesterday and have been listening to them all day long.

ReplyDelete"There Is a Light That Never Goes Out" is especially wonderful.