Paul Verhoeven's Soldier of Orange was the film that started him on the path to Hollywood, the film that made no less than Steven Spielberg take notice of the Dutch talent. It's not hard to see why: it's an epic, masterfully made film, a brisk, constantly moving wartime adventure about friendship, betrayal and the ways in which people can stumble upon their principles. The film traces the lives of a group of rowdy friends between 1938 and 1945, from their time at a Dutch university to their entanglement in World War II, as their home country is dragged into the conflict by Hitler's invasion. These youths are initially far from interested in the war or Germany or anything else. They expect their country to remain neutral, as usual, and if anything many of them are sympathetic to Germany, nursing some of the same anti-Semitic sentiments as Hitler and his followers. So they play tennis, and go to parties, and compete over women, oblivious to the impending chaos about to engulf Europe. When Britain declares war against Germany, a few off them are troubled, but most don't care: they simply switch off the radio and return to their tennis match and their gaiety. This only changes when Germany actually invades Holland, bombing civilian targets and sending in soldiers.

What Verhoeven's interested in here is defusing the usual war movie clichés: the over-the-top patriotism, the stoic heroes, the girl loyally waiting back home. He signals his subversive intent, subtly, in the opening scenes. After a mock-newsreel introduction of the Dutch Queen returning to her own soil after the war, greeted by an extravagant welcome, the first scene of the film proper is a noisy, chaotic sequence in which a group of shaved-head young men are berated, beaten and mocked by neatly dressed men who order them around like drill sergeants. The film's subject, and its opening (with a credit sequence accompanied by the Dutch flag), prime the viewer to interpret this scene through the filter of World War II history: the shaved heads, the shouted commands, the sniveling men who seem to be prisoners. Actually, it's a particularly brutal fraternity hazing, and its end result is to forge a lasting friendship between new recruit Erik (Rutger Hauer) and the fraternity president Guus (Jeroen Krabbé).

Verhoeven patiently explores the pre-war life of these young men, upper-class boys studying to be lawyers and take their place in society. Their lives are disrupted by Hitler's bombs, and the German invasion forces them to make difficult choices, to choose sides. Guus and Erik will join the underground resistance against the Nazis, along with friends like the Jewish boxing champion Jan (Huib Rooymans), the resourceful organizer Nico (Lex van Delden), and Robby (Eddy Habbema), who runs a transmitter sending messages to England. Erik's friend Alex (Derek de Lint), who has a German mother and thus sees the situation somewhat differently, joins the fascist army and goes to fight in Russia. Others, like Jack (Dolf de Vries), simply lay low and wait out the war at home, secretly completing his degree and preparing for post-war life even while the bombs are falling and his countrymen are dying and fighting back. Verhoeven doesn't want to present a simplistic portrait of patriots fighting for their country: these are real people, with complex relationships and complex reasons for what they do. The film is based on the real story of Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzema, the aide to Queen Wilhelmina whose book about his experiences provided a starting point for Verhoeven's film.

Indeed, Erik is a hero, but he arrives at it only slowly, even reluctantly. He dabbles in the resistance, but his efforts are wasted, and he sees his friends and allies dying and being captured, seemingly betrayed. The Germans strategically allow him to overhear that they have a spy in London, a man named Van der Zanden (Guus Hermus), then they release him. So when Erik gets the chance to escape to London, he does so, along with his friend Guus, intending to help out in any way he can and especially to expose the traitor who may have been compromising the Dutch resistance. As usual with Verhoeven, such things are more complex than they seem at first. The supposed spy turns out to be a staunch ally of the Queen, and the traitor within the midst of the resistance has his own reasons for doing what he does. Robby turns out to be the weak link in the organization, agreeing to help the Germans when they threaten to take his Jewish fiancée Esther (Belinda Meuldijk) to a concentration camp.

The emotions in this film are complicated and subtle, especially for a war epic with action taking place on a grand, international scale. Verhoeven never forgets about the human dramas, never leaves behind the characters and their smaller stories in favor of the big picture. What's striking, then, is that everything that happens here amounts to so little, does so little to affect the outcome of the war either way. These people and their struggles are peripheral to the main thrust of the war, as the British officers themselves acknowledge: they're using the Dutch fighters mainly as a distraction, throwing Erik and his compatriots at the Germans in order to waste the enemy's time, to draw their attention away from more important matters. Verhoeven's storytelling is taut and his action sequences are suspenseful and perfectly conceived, and yet by the end of the film it's obvious that virtually nothing has been accomplished by all these intrigues and missions: Erik presumably does much more in his mostly unseen bombing runs than he did throughout the entire rest of the film. Verhoeven is interested in history, but he's interested in it largely as it happens on the ground, as it affects individuals and their small, historically minor lives. He is bringing historical footnotes to life, investing their stories with all the grandness and nuance and detail usually reserved for major players in these struggles. Despite the opening, in which Verhoeven skillfully blends faux-period footage of Hauer in with genuine newsreel footage, this is not a Forrest Gump kind of historical movie, in which the characters wander through major historical events. Instead, this film is all about unraveling the tightly knit story of abstracted history into the individual threads that comprise it, each small strand insignificant in itself but each adding to the cumulative experience of a time and place.

This is rich stuff. Verhoeven, so often thought of as a director of big, bold gestures and over-the-top stylization, is actually just as capable of subtlety and restraint. He largely hints at the deep emotional bonds linking Erik to his friend Robby's fiancée Esther. The two have a halting, infrequent affair, succumbing to passion for one another at times of stress, but Verhoeven communicates their longings largely through glances, through silent moments in which a great deal seems to pass between them. There is a wonderful, perfectly staged scene late in the film, when Erik begins to suspect that Robby is a traitor when he sees all the nice things that Esther has at their house, at the peak of wartime in Holland. She tells him that Robby gets all these things for her, things that Erik couldn't even get in England, through his friends in the resistance. But when Erik asks her if she really believes that, she pauses and simply shakes her head, just once, from side to side, her face steeled but her eyes sad. There is so much in that gesture, the resignation and defiance and the knowledge that her man has betrayed his principles, betrayed even his friends in order to keep her safe, and that even though she is torn up by it she has gone along with it, has allowed him to do it and allowed him to think that she doesn't know. This all happens beneath the surface, again in the exchange of looks between Erik and this woman who he loves, but who various circumstances have kept from him.

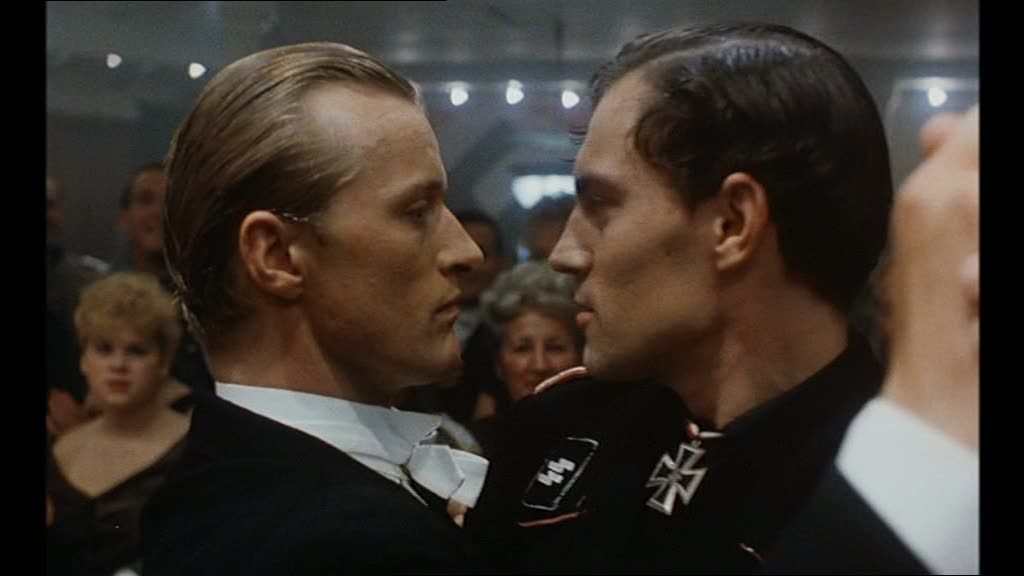

There is a similarly great dynamic at work in London, where Guus and Erik engage in a friendly rivalry to bed down the pretty English military secretary Susan (Susan Penhaligon). Again, a lot happens between the lines, as Susan flirts with both men, inviting Erik under the covers to join them after she and Guus have had very public sex in a second floor window, with Erik down below hilariously trying to prevent the Queen from getting an eyeful. Verhoeven allows a great deal of ambiguity in the way Susan manages the rivalry of these men for her affection: when she conspires to have Guus and not Erik sent on a dangerous mission, is she trying to maneuver the man she wants closer to her, or trying to make the man she already has a hero? Also implicit in these scenes is the homosocial love of Guus and Erik for one another, a love that transcends their sparring over Susan, even when she lays naked in between them. Later, this kind of love between men will bridge even the opposing sides of the war. One of the film's most memorable sequences is the extended tango that takes place between Erik and the fascist soldier Alex, when Erik stumbles undercover into a party for the Nazis. The two men dance together, their faces just inches apart, their hard profiles seemingly on the verge of a kiss, and discuss the vagaries of history that have made them enemies rather than friends.

Soldier of Orange is a typically dense, potent epic from a director who consistently manages to find the difficult and powerful emotions within blockbuster material. This is a deeply personal and contemplative war epic, even as it moves at a brisk, thrilling pace. It satisfies every expectation of its genre, packing its lengthy running time with battles and betrayals and suspense sequences — like the indescribably tense climax on a Dutch beach guarded by the Germans — and yet it is also subtle and humanistic. It's a film about the tight interplay between choice and fate in determining the flow of a person's life during times of upheaval. And it's also a visceral, rousing action picture. Verhoeven is one of the few directors who is able to have it both ways, while compromising neither.

Excellent review, Ed. This is one that I saw on a whim and did not know what to expect from it, but I was glad that I gave it a chance. Your description of the unraveling of this grand historical event into its individual strands is a great analysis of the film. I also like how Erik is handled... he's a "hero," but reluctantly. A lot of times when directors try to portray a reluctant hero it comes across as very forced. That is not the case here at all.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Dave. I agree about the handling of Erik -- too often films that have a "reluctant hero" at their center try to lean too hard on the hero part, afraid to make him too unsympathetic. Erik really comes across as a guy who just kind of stumbled into a rough situation that he really didn't want to be involved in. Verhoeven's characterization is very ambiguous and multi-layered, especially in the way Erik is almost fiercely loyal to his friends even as he has this bad habit of falling in love with their girlfriends.

ReplyDelete"What Verhoeven's interested in here is defusing the usual war movie clichés: the over-the-top patriotism, the stoic heroes, the girl loyally waiting back home. He signals his subversive intent, subtly, in the opening scenes."

ReplyDeleteAye, quite right. And this is (as you contend) an intricate, rich and multi-layered emotional film, that I consider one of it's director's finest. Erik's 'reluctant hero' status is indeed what's most fascinating here. I completely agree with Dave that this is a great review, which again leaves no stone unturned. It makes me want to look at this again. That's always the sign of something special. It's interesting that it's loosely based on a real-life situation.

"especially in the way Erik is almost fiercely loyal to his friends even as he has this bad habit of falling in love with their girlfriends."

ReplyDeleteThis is spot on, but this phrase definitely made me chuckle! It's absolutely right, and it's funny to think about how true it is.

Excellent review of a great, overlooked film. His newer film Black Book reminded me of this one, but this film is better. It manages to be a true war film without miring in cliches, and yet has a unique spirit. Rutger Hauer, what happened?

ReplyDeleteTommy, I love Black Book; it's my favorite Verhoeven film, in fact, and it's also my choice for the TOERIFC film club, to be discussed in July. You're right that it's obviously developed from the template of Soldier of Orange, but I don't want to say too much more about it here. Have to save up my thoughts about that one 'till July.

ReplyDeleteAnd yeah, Rutger Hauer is so good in his Verhoeven films that the subsequent arc of his career is just baffling.

I am not a fan of BLACK BOOK, although I do admire Carise Van Houten's performance. Does this mean I am banned from TOERIFC??

ReplyDeleteJust kidding. I look forward to your insights.

Quite to the contrary, Sam, I fully expect to get some negative opinions of Black Book when I host the discussion about it. In fact, it'd be a pretty boring conversation if everyone agrees, and one of the good things about Verhoeven is that he can always get people talking, whether they love or hate his work.

ReplyDeleteI've always wanted to see this, despite not being much of a Verhoeven fan. It sounds up my alley, but then so do a lot of his films, and I'm generally disappointed.

ReplyDeleteEd, what do you think of Flesh and Blood?

Not to get your hopes up too much, Bill, but you might enjoy this one even if you're not usually a fan. It's less extreme and more straightforward than many of his other films. It's recognizable as Verhoeven, certainly, but slightly more restrained for once. What usually bothers you about him?

ReplyDeleteFlesh and Blood is the next of his films I'm going to watch. Unlike you, I have yet to be disappointed by one of his films, so I'm looking forward to it.

I don't mind extreme or, er, un-straightforwardness. I just never think his satire is that clever, or funny, except maybe in Robocop, and when he shocks, I get the sense that shock is all he had on his mind. Though I should probably add that I've seen relatively few of his films, and haven't watched Black Book, which I actually have high hopes for (and had those hopes well before you picked it for TOERIFC, so fingers crossed, and all that).

ReplyDeleteAnyway. If you like Flesh and Blood, then, well, more power to you, I guess.

Out of curiosity, which films have you seen? For my part, I think he's often funny and that his shocks are fairly complex and rarely *just* about being shocking. I get the sense that he wants to make viewers uncomfortable, yes, to shock them, but that he does it in order to provoke them into thinking about their genre expectations, and also because he genuinely views sex and shitting and other physical processes as just a part of life that should be up there on the screen like anything else.

ReplyDeleteOf course, none of this really applies to Soldier of Orange, which isn't remotely shocking, so maybe you should make it your next Verhoeven stop, especially since it's so closely related, thematically, to Black Book.

I've seen the aforementioned Robocop, Starship Troopers (feh!), Total Recall, Hollow Man, Basic Instinct (I know, it's all looking very commercial so far, isn't it?), half of Showgirls at regular speed, the other half at FF speed, Flesh and Blood, The Fourth Man...and I think that's it. So I guess more than I thought, but mostly his Hollywood stuff, but I've always been under the impression that his fans take those as seriously, in some cases, as his Dutch films, so...

ReplyDeleteAs much as I don't agree with your low assessment of the Hollywood films (and I would cite Starship Troopers as the best of those!), I do think his Dutch work is not only better, but helps to put his later work into its proper context. Then again, if you didn't like The Fourth Man either, maybe Verhoeven just isn't for you.

ReplyDeleteEd: A fine review of a film I haven't seen in a number of years but one that I still remember quite clearly. It's not my favourite Verhoeven film, but nonetheless is one that shows a different facet of his filmmaking career, and, as you say in these comments, one that is thematically connected to his last film Black Book.

ReplyDeleteBill: I agree with Ed. You should track down some more of his early Dutch films, which not only show his range as a filmmaker, but also helps to contextualise his Hollywood period to an extent. Soldier of Orange would be a perfect place to start, as it shows Verhoeven at his most restrained but still at the peak of his filmmaking abilities.

However, as Ed suggests, if you don't like The Fourth Man, there's a good chance that Verhoeven's work (at any point in his career) just isn't for you. I can't imagine someone who dislikes The Fourth Man getting much out of Turkish Delight, Keetje Tippel or Spetters (my favourite of his Dutch films), all of which play with very obvious concepts of melodrama and fairly in-your-face sexuality.

To be honest, it's been so long since I've seen The Fourth Man, and I remember so little about it, that I can't honestly say I don't like it. I didn't at the time -- though I can't say I remember hating it, either -- but who knows what I'd think if I watched it again.

ReplyDeleteAnd I don't mind in-your-face sexuality (far from it!) or playing with melodrama, or any of that. I just don't like the way Verhoeven handles it.