[This is a contribution to the Claude Chabrol Blog-a-Thon currently running at Flickhead from June 21 to June 30. For the last ten days, Flickhead has been dedicated to the works of the French New Wave master, and I've been following along with many reviews of my own.]

Poulet au vinaigre is a quirky black comedy in which Claude Chabrol, always eager to skewer the bourgeois and expose their foibles, focuses on the shady business dealings, love affairs and murderous impulses of a group of small-town businessmen. This mess is all stirred up and brought out into the light, appropriately enough, by the investigation into the one crime these thieving, conniving monsters didn't commit — the accidental death of one of their number, the butcher and strongarm man Filiol (Jean-Claude Bouillaud), in a car accident after someone puts sugar in his gas tank. This incident brings the dogged inspector Jean Lavardin (Jean Poiret) to town, and he is not satisfied with simply investigating this car accident. Instead, Lavardin begins digging into the town's affairs, turning up all sorts of ancillary crimes and juicy rumors, most of which he seems much more interested in than in Filiol's death. One of the film's subtle running gags is how, whenever Lavardin appears, he is referred to as the detective investigating the Filiol case, usually right before he begins asking about something else entirely, probing into everything but the case he's really supposed to be solving. His methods are fierce, too, and probably not entirely legal: he beats suspects and dunks their heads in a sink full of water, breaks into apartments without warrants, and generally has little concern for paperwork or procedure. When someone tells him he can't get away with this, he replies, with a twinkle in his eye, "Ah, the police can do anything!"

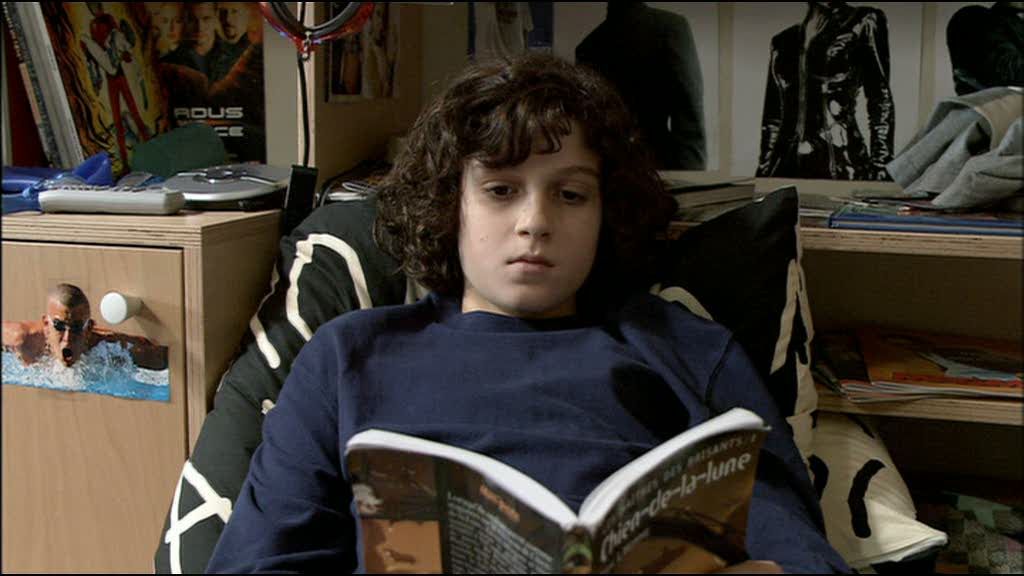

This cheerfully brutal, fascistic personage is nevertheless Chabrol's stand-in within the film, and it must surely have been satisfying for Chabrol to turn the bourgeois' most dependable ally, the police, against them. Lavardin is a vicious bloodhound, a thug with little moral compunctions or respect for the law, and yet his doggedness, when turned against this town's most respected residents, manages to unearth their previously well-hidden crimes. It is appropriate, also, that the trigger for Lavardin's investigation is actually one of the town's less fortunate residents, the young postman Louis Cuno (Lucas Belvaux, who looks and acts like a French Michael Cena, all hangdog reserve and stumbling shyness). Louis lives in a dilapidated old house along with his crippled, half-crazed mother (Stéphane Audran), who still mourns the loss of her husband, who ran away twelve years ago. She jealously protects her home, guarding it against the real estate schemes of a trio of local businessmen: Filiol, the solicitor Hubert Lavoisier (Michel Bouquet) and the doctor Philippe Morasseau (Jean Topart). These unscrupulous crooks want to buy up the Cunos' land and move them to another house, for unspecified reasons; it's clear only that it would doubtless be a bad deal for the Cunos, and that something shady is up.

As a result, Louis' mother spends most of her time plotting and spying on their enemies; Louis, on his postal delivery routes, brings home any mail intended for the three businessmen so his mother can steam it open in the basement and read it before passing it along for delivery. But there's more than just shady land deals going on: Morasseau's wife Dominique (Josephine Chaplin, glimpsed only briefly during the opening credits) has disappeared, which makes her friend Anna (Caroline Cellier) suspicious. Chabrol deliberately muddies the water, creating complex webs of relationships and passing along much of the information about what's going on second-hand, through gossip and intercepted letters and photos that get passed around from person to person. Everyone's sleeping with everyone, everyone has secrets, and the nights in this town are a time for secret meetings, everyone skulking back and forth through the dark streets towards mysterious ends. It's both a parody of murder mystery conventions and a joyous fulfillment of the genre's requirements, even if in the end everything that's going on is exactly what one expected.

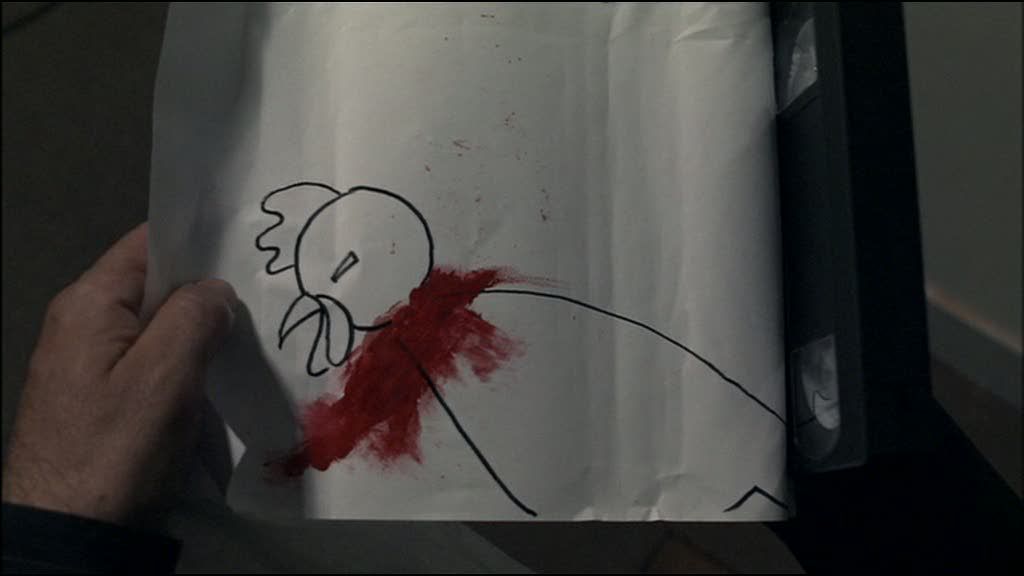

More than these mystery movie shenanigans, though, Chabrol is interested in the subtexts, both psychological and social, that are opened up by all these complicated plots and counterplots. Not least of these is the predicament of poor Louis, whose possessive, disturbed mother lives in fear of him leaving one day, like his father did, and thus discourages all girls as sluts trying to take her son away from her. This places Louis in an uncomfortable position between his mother, who he cares for with grudging love, and Henriette (Pauline Lafont), the voluptuous, perky girl he works with, who teasingly seduces him any chance she gets. There's an unspoken war between these two women, who never meet, over the young man who gets tugged back and forth between them, dealing with their ultimatums and their possessive demands, trying to keep both happy but knowing he can't. Poor Louis just gets kicked around by everyone — by Lavardin, by the town's businessmen, by his unpredictable mother — and that's probably why he's quietly seething inside, ready to explode with violence. When he gets some wine into him on a date with Henriette, he becomes someone else, confident and angry and defiant.

So on one level the film's about growing up, breaking free of the nest, escaping from the trap of the home to live one's own life: Louis faces this choice more explicitly than most at the film's finale, when he is framed in the center between his mother and his lover, having to choose which he'll go to. More than this, however, Chabrol is interested in what's going on around this teenage psychodrama. Louis, his mother and Henriette are important figures in the larger story, but they're also outsiders to it because they are of a lower class (though the Cuno home is big enough that, had Louis' father stuck around, it's obvious their situation would have been quite different; then they'd be a part of the bourgeois rather than its victims). They're part of the town's lower layer, providing basic services and doing all the real work that gets done in this film. Chabrol creates a fully functioning small town here, populating the fringes of the narrative with some of his regular troupe of actors, including the always hilarious Dominique Zardi as an obsessively punctual post office manager, Marcel Guy as a talkative barkeep, and Henri Attal as a morgue employee who's easily bribed with a stick of gum. All these characters drift around the outer edges of the film, adding to its complexity, creating the impression of a real town with all its cross-currents and linkages and intrigues.

Ultimately, Poulet au vinaigre takes some of Chabrol's characteristic themes and deals with them in a lighter context than usual, using this convoluted story of murder and deceit as a loose framework for the film's satirical and comedic digressions. It's all treated with an irreverent tone, a slightly askew sensibility that displays Chabrol's wry perspective on these characters.