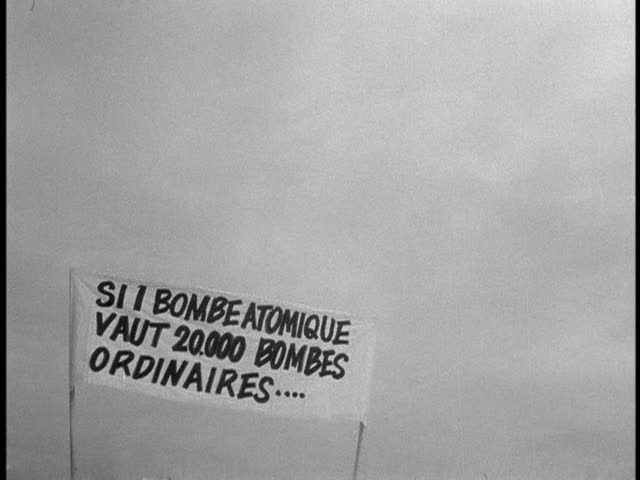

Alain Resnais' debut feature, Hiroshima mon amour (following a long string of short documentaries that included the bracing Holocaust film Night and Fog) was one of the opening salvos of the French New Wave. It remains a potent, intellectually stimulating work, a sustained examination of the bonds connecting nations, and the large gulfs of experience and understanding that separate them. The script, by the novelist and future filmmaker Marguerite Duras, keeps the story at an entirely abstract level. The main characters, a French woman (Emmanuelle Riva) and a Japanese man (Eiji Okada) are unnamed, and their relationship is developed primarily as a symbolic way of working out the tensions inherent in trying to understand a foreign culture, and especially a foreign culture that has experienced something as devastating and historically unprecedented as the explosion of nuclear bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The French woman has traveled to Japan to act in an anti-nuclear movie about Hiroshima, and while there she engages in an affair with the Japanese man. Throughout the film, they exchange dialogues during which she tells him about a traumatic experience in her past, about her doomed affair with a German soldier in occupied France during the war, and her disintegration and suffering in the war's aftermath.

As the film shifts fluidly between the couple's dialogues and images from the woman's past, Resnais and Duras probe the different wartime experiences of the French and the Japanese, and the barriers to true understanding. In the film's justifiably famous opening, the two lovers speak in voiceover while the images illustrate their conversation about the tragedy of Hiroshima. The woman believes that she understands what happened because she has seen the reconstructed city, has visited the museum where photographs and objects testify to the destruction of Hiroshima, has seen the movies that re-enact the horrors. While the woman enumerates these things, the man keeps reiterating that she does not understand, that she has truly seen nothing. This essayistic opening, in which the two lovers appear only as disconnected body parts, covered in ash as they embrace, connects back to Resnais' short film work. The first 15 minutes of the film are nearly a complete essay-film in themselves, encapsulating Resnais' themes and ideas, which are then expanded upon by the remainder of the film.

Yes indeed, this is one of the seminal works of the New Wave, and one of the most abstract of cinematic works. I like the film, but I prefer NUIT ET BRULIARD and LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD. Of course Resnais's ability to transcend singular modes of expressions makes them difficult to compare. But it's still a masterpiece, and I can't at all fault you for including it in your most revered category here at OTC. I don't concur with those in the critical establishment who call the film "dated" as that kind of generalization can also be aptly applied to other films that they themselves embrace. It's setting is integral to its thematic interpretation.

ReplyDeleteIt does have one of the most celebrated of all openings in film. It's a film you always get more from on re-viewings, a usual barometer of greatness.

Thanks, Sam. I find Resnais' great films difficult to compare, especially Night and Fog against his fiction features. Night and Fog is one of the towering masterworks of cinema, no doubt about it, but somehow it seemed slightly wrong to excerpt it here like this. So instead I included this one, a worthy second place. I definitely don't think it's dated -- or "pretentious," the other accusation often lobbed at it, and at Resnais in general. I appreciate Resnais' willingness to be intellectual and abstract, to really challenge people by offering up what only seems to be a narrative. Actually, it's barely a story at all, but as much of an essay as Night and Fog or Last Year in Marienbad.

ReplyDeleteOf Resnais' work, I've really only seen this one and Not on the Lips in their entirety. But I love your analysis of the first 15 minutes especially. Thanks for sharing your views. :)

ReplyDeleteThis is a masterful film with remarkably sensuous photography. Your analysis is spot-on, discussing the film as an ostensible narrative, but with greater emphasis on symbology, the namelessness of the characters being the key point. I also love Emmanuelle Riva's performance, which, despite her use as a purely metaphorical figure, manages to be extremely personal and plausible. Great choice for "Films I love".

ReplyDeleteOnce again I'm in full agreement, since it's all a favourite of mine. At the time I saw it (late 70s) it got me hooked on Duras' works which I collected and read most all of. The movie is very close to her style of writing.

ReplyDeleteBy the way, Marguerite Duas has alos done some amazing work as a movie director. Her movies are probably hard to find, but likely I was able to attend a full retrospective at the Munich film festival about 2 decades ago.

Thanks for the comments, all.

ReplyDeleteJuliette, for me the first fifteen minutes are the key to the film and its best part; it'd be a great film just for that even if the rest of the film was inconsequential.

Carson, I agree about Riva, who brings some warmth and feeling to what would otherwise be an entirely abstract film. She makes her unnamed character a person rather than just a concept.

William, I wish I could say I'd seen some of Duras' own work as a director, but alas she remains a blind spot for me. I have to correct that soon, as this film is clearly as much her work as Rivette's.

I think using a couple's love affair as a metaphor for the tragedy of Hiroshima is about as pretentious as you can get, at least in theory, but somehow Resnais manages to makes it work. In some ways, I wonder if Resnais is utilizing the film's love affair as a commentary on his work in documentaries like Nuit et brouillard, demonstrating that not even filmed footage of historical tragedy can ever truly equal the actual experience of the tragedy, just as the two lovers can never truly experience intimacy between themselves. Moreover, nor can we, the passive spectators, ever fully partake in whatever intimacy the lovers do manage to find between themselves. As much as the cinema is a window into the world, particularly as a form of documentation (as illustrated here), it is also essentially--and I believe Resnais understands this--a window sealed shut, allowing one to observe but never completely interact with what's on the other side of the glass. Maybe Resnais is applying this concept to the intrinsic barriers of romantic love; he is at least--as you point out, Ed-- applying it to the way we perceive historical tragedies which exist outside our own national borders.

ReplyDeleteThat's a very interesting take on the film, J. I agree that the concept here, in itself, makes it sound like the film would be unbearably pretentious -- but Resnais is intellectually precise enough that he, and perhaps only he, can make it work.

ReplyDeleteI really like your breakdown of all the levels on which the film is about communication barriers and gaps in understanding: between lovers, between artists and their audiences, between different cultures, between art and reality, between the image and the event or person it represents. All these disjunctions flow throughout the film, which again and again returns to the idea that we can easily *observe* something that exists outside of ourselves, but fully understanding it is more difficult.