Michael Haneke's The White Ribbon, his first German-language film since his original Funny Games from 1997, is a searing, enigmatic allegory, a depiction of horror and cruelty overtaking a small German town on the eve of World War I. The film is powerful and quietly moving, slowly building a sense of pervasive dread as the town's routine business is disrupted by explosions of horrifying violence and brutality, by incidents that expose the everyday nastiness lurking beneath the rural calm that the town presents on its surface. What makes the film so effective as an allegory is that, as in Caché, Haneke withholds all easy answers and all resolutions; the film is a mystery with no solution, leaving its ultimate meaning to the viewer. It is also perhaps Haneke's most emotionally rich film, built around a large cast of complex, ambiguous characters, people beaten down and made cruel by the harsh surroundings and morally fallow ground of the countryside.

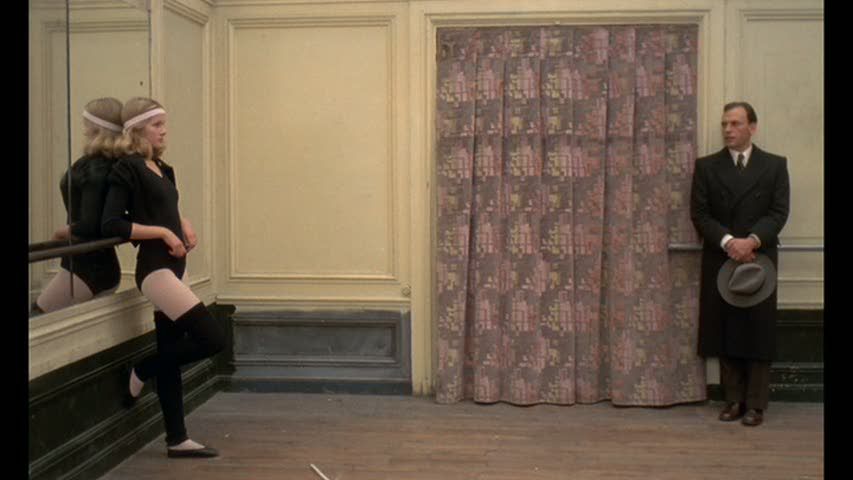

The film is an angry indictment of the hypocrisy and violence that resides within these seemingly decent folks, many of whom are obvious symbolic stand-ins for various social institutions, all of them equally corrupt: the aristocracy, the proletariat, the church. The Pastor (Burghart Klauβner) might preach decency and goodness in mass every week, but with his own children he is a brutal disciplinarian who reacts to the slightest infraction with hands-on correction. When his oldest children Klara (Maria-Victoria Dragus) and Martin (Leonard Proxauf) are late for dinner one night, he responds by sending all the children to bed without dinner and delivering ritualistic whippings the next morning. He also marks the kids with the white ribbons of the title, which are symbols of purity and innocence to continually remind them of the qualities they should aspire to. This man of God is obsessed with his abstract values, but in putting them into practice he's cruel and intractable, refusing to understand whatever's going on behind his children's blank, mysterious faces. The town doctor (Rainer Bock) is even worse, a nasty man with all kinds of secrets lurking within his home. He's sexually abusing his young daughter, who he creepily insists looks just like his dead wife, even as he's also having sex with his matronly midwife (Susanne Lothar), who he treats with contempt and outright cruelty, scorning her love.

Meanwhile, the Baron (Ulrich Tukur) and Baroness (Ursina Lardi) are aloof from the others in the town, projecting an aura of privilege and exploiting the labor of the commoners — they send one woman, too weak to do heavy harvesting work, into a dangerous area of a sawmill, where she falls through the rotted floor to her death. This is only one of the horrifying incidents that begin to affect this town, as the people's behind-the-scenes petty cruelties and domestic evils are written onto the very surface of the town, in one public spectacle after another. The doctor's horse is tripped by a thin wire and the Baron's son Sigi (Fion Mutert) is hung upside down in a barn and beaten badly, among other tragedies and acts of violence, all of them utterly mysterious, none of them ever solved. It is as though the people of the town are finally revolting against the brutality and indifference they experience behind closed doors every day. It is never clear if there is one perpetrator behind all these crimes, or if they are each the products of specific vengeful quests. As in Caché, Haneke leaves the mystery's solution fuzzy because the "who" matters far less than the symbolic import of these acts. As in Caché, the mystery here is not a matter of plot and action but an internal mystery, a mystery of the soul, a mystery about how violent acts are passed down through generations and how the chain of violence might be broken if only one generation would refuse to continue the cycle.

Often, these crimes are committed against or involve the town's young, who are affected in various ways by the sins and violence of their elders. This is the film's central thrust, the ways in which innocence is corrupted or destroyed in the presence of evil, a struggle that is far less abstract for Haneke than it is for the town's Pastor. All of the town's children are wounded by the older generation. Some of these kids maintain their innocence and innate goodness. The pastor's youngest son is a sweet, caring boy who takes in a wounded bird and agrees that after he heals it, he will set it free, even though the prospect obviously makes him sad — and then, when his father's bird dies, he offers his own as a replacement, a selfless act that seems to move even the unshakable priest. The doctor's young son is a similarly angelic young soul, who when his father is injured packs up his clothes and sets off on a journey to see his dad in a nearby town. The midwife's son Karli (Eddy Grahl) is another avatar of innocence and purity, and he has to suffer because of it, beaten and bloodied merely because of his guileless lack of the corruption that flows through so many of the town's other inhabitants, adults and children alike. Another child who suffers in innocence is the steward's daughter Erna (Janina Fautz), who says that she has precognitive dreams of horrible things about to happen; when she predicts the beating of Karli, the police hound and question her, believing that she knows who did it, causing her to break down in frustrated tears.

While many of the town's children represent purity and goodness in this way, there are others for whom the corruption of their parents seems to weigh heavier. Martin and Klara, certainly, are haunted by the great demands placed upon them by their religious father. In one of the film's most telling — and darkly humorous — scenes, the Pastor confronts Martin, who is increasingly looking sickly and depressed, his eyes ringed with black, his face sunken in and his eyes skittish. The Pastor responds by telling the boy a lengthy story about another boy who showed many of the same symptoms, eventually broke out in boils all over his body, and died. And what caused this, the priest asks? The boy was exciting his "nerves" in a forbidden place, of course, a ludicrous euphemism for masturbation. The scene would be hilarious if it weren't so depressing, if the Pastor didn't display such a profound ignorance of his son and such disinterest in actually getting to the bottom of what is obviously bothering the boy. Instead, he responds by tying Martin to his bed every night, so that he can't touch himself in the night. Could this really be what was bothering Martin, this guilt over masturbating? Or was he haunted by something darker and more real, something his father will never be able to understand or even glimpse because his mind is too fenced-off? The Pastor is too rigid in his ideas about sin, discipline and self-control to even imagine having a candid conversation with his children about anything.

These are the questions at the core of The White Ribbon: how guilt and sin flow through generations, affecting the young and innocent in unpredictable ways, sometimes corrupting their decent souls and sometimes simply injuring them, scarring them in ways likely to echo throughout their lives. Haneke's basic theme here is that innocence can't last, that goodness is ephemeral and quiet in comparison to the overpowering darkness of violence and hatred. The doctor's son, early in the film, asks the midwife about death, and with wide eyes listens as she bluntly tells him, trying to dull the impact by repeatedly stressing that this will happen only in "a very long time." He gets the idea anyway, and his awareness can't be taken away from him; he understands things with a new completeness, instantly getting that the stories about his mom being away on a trip had simply been a euphemism for this new concept called "dead."

The film is unrelentingly bleak and sad at moments like this, capturing the dawning of understanding and the accompanying loss of innocence; Haneke laments this loss, and treats it as a richly emotional moment. Only the film's narrator, the local schoolteacher (Christian Friedel) and his fiancée Eva (Leonie Benesch) are ultimately able to maintain their innocence and goodness. They aren't showy about it in the way of the Pastor, but they are moral and chaste in all their interactions, possessed of a basic deep-down goodness that sets them outside of the town's horrors, and outside the horrors of history as well, their simple romance unshaken by the reverberations all around them. As the narrator, the teacher's sporadic voiceover steps in to position this story as a thing of the past, and thus as a lesson about the present — but a lesson whose meaning isn't necessarily clear. The film would be nearly unbearable if not for Haneke's suggestion, in the story of these two characters, that there is light and goodness within all the darkness, that there are those who remain unstained by the bloody crimes happening all around them.

Haneke's dark wit also leavens the grim mood, revealing itself in subtle ways throughout the film, particularly in his cutting. At one point, as the teacher romantically plays the organ for Eva, Haneke cuts him off in mid-note and abruptly cuts to a farm scene, with a pig squealing on the soundtrack, dissonantly continuing the music. Even better is the moment when, after Martin confesses to his father that he was masturbating — more out of resignation than because it's actually the truth, most likely — Haneke cuts immediately from the boy's downturned face to the doctor in mid-orgasm, having disinterested sex with the midwife. These bleakly humorous transitions characterize this film, which maintains Haneke's general wry, distanced observation of his characters' follies and cruelties. He captures their misery and brutality in stark black and white, leaning towards washed-out whites in many scenes, giving the film a very clean, crisp, wintry atmosphere, best portrayed in several shots of snowy whiteout landscapes, as pure and untouched as a child's conscience. The film's bleak aesthetic and emphasis on long takes — a funeral plays out entirely in a single wide shot, a horse-drawn carriage waiting in the snow to pull the coffin — recalls the cinema of Béla Tarr, one obvious reference point for a film that's both completely Haneke and also something of a departure for him.