20. THE FILTH/SEAGUY

by Grant Morrison, Chris Weston & Gary Erskine, 2002-2003

by Grant Morrison & Cameron Stewart, 2004

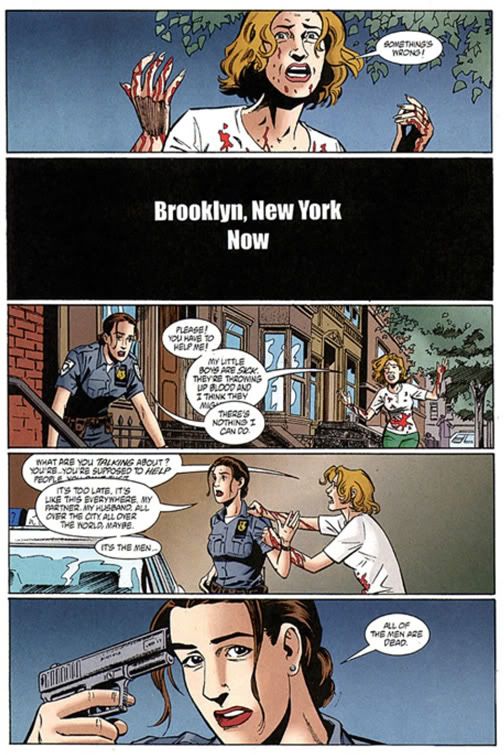

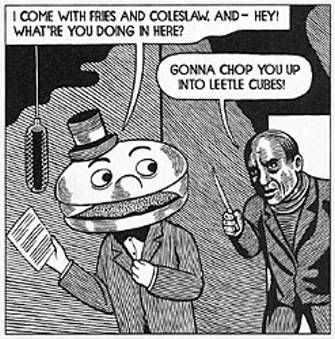

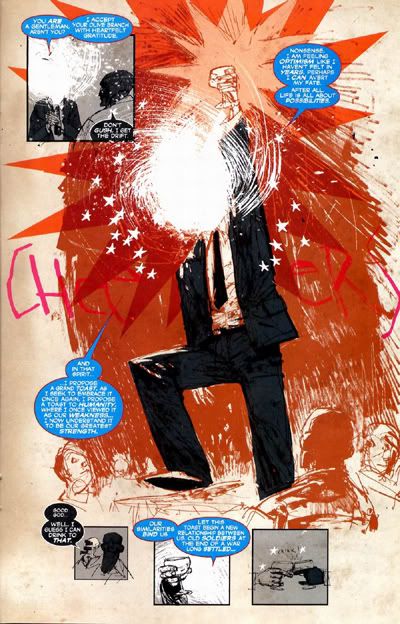

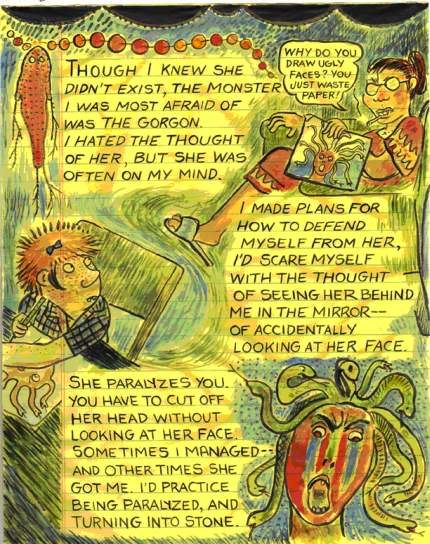

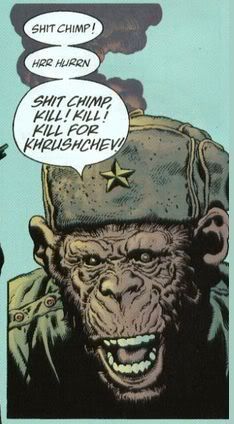

The Filth is the perfect expression of Grant Morrison's paranoid, conspiratorial view of the way the world works. It condenses, in its relatively compact twelve issues, the thrust of Morrison's sprawling series The Invisibles. It returns to familiar territory — the malevolent forces controlling the world, the suppression of individuality, the power of sexuality and transgression to overcome such oppression — and does so with Morrison's characteristic blunt humor and restless imagination. Because of its limited miniseries length and the sheer variety of ideas and images it encompasses, it is perhaps Morrison's densest and most tightly packed work. It is raw, undiluted Morrison, leaking wild ideas and constantly setting off on loony digressions and detours. It's about the Hand, a secret agency dedicated to maintaining the status quo by destroying anything that threatens to introduce new, destabilizing elements into the balance of world power, or new ideas into the popular discourse. The book posits a whole behind-the-scenes network dedicated to keeping the reins on sexual and scientific knowledge, even as perversity and mad science rage through the corridors of power. The art of Chris Weston (with inker Gary Erskine) lends a gritty plausibility even to Morrison's most out-there visions, and the book especially benefits from its unified creative team, since uneven artwork has often plagued the writer's longer projects.

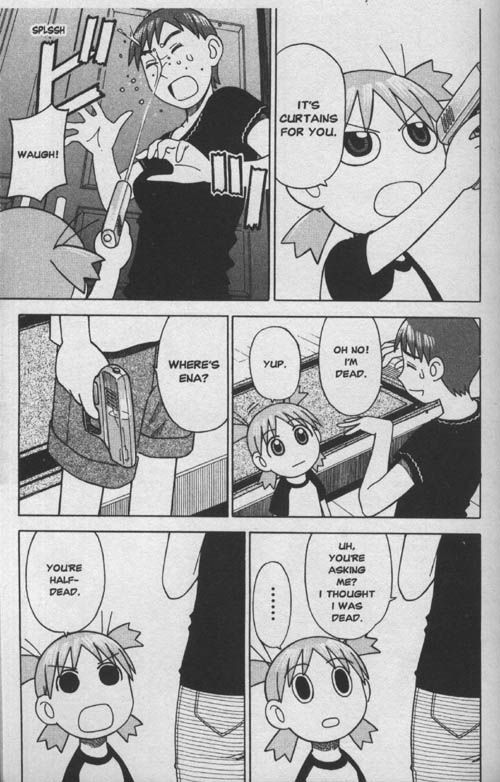

The Filth is the perfect expression of Grant Morrison's paranoid, conspiratorial view of the way the world works. It condenses, in its relatively compact twelve issues, the thrust of Morrison's sprawling series The Invisibles. It returns to familiar territory — the malevolent forces controlling the world, the suppression of individuality, the power of sexuality and transgression to overcome such oppression — and does so with Morrison's characteristic blunt humor and restless imagination. Because of its limited miniseries length and the sheer variety of ideas and images it encompasses, it is perhaps Morrison's densest and most tightly packed work. It is raw, undiluted Morrison, leaking wild ideas and constantly setting off on loony digressions and detours. It's about the Hand, a secret agency dedicated to maintaining the status quo by destroying anything that threatens to introduce new, destabilizing elements into the balance of world power, or new ideas into the popular discourse. The book posits a whole behind-the-scenes network dedicated to keeping the reins on sexual and scientific knowledge, even as perversity and mad science rage through the corridors of power. The art of Chris Weston (with inker Gary Erskine) lends a gritty plausibility even to Morrison's most out-there visions, and the book especially benefits from its unified creative team, since uneven artwork has often plagued the writer's longer projects. The even more compact three-issue miniseries Seaguy offers up a similar, subtly disturbing nightmare vision of authoritarian control and conformity. On its surface, Seaguy looks and feels like a goofy superhero/adventure parody, with the clean, cartoony art of Cameron Stewart and some of Morrison's most pulpy, poppy dialogue. But as Morrison pulls back the layers of Seaguy's brightly colored, seemingly idyllic world, darker subtexts begin creeping in. Seaguy is a third-string superhero in a world that doesn't need heroes anymore, because the populace is uniformly happy and sedate, convinced by mass media marketing to be docile worker drones for the government and its corporate allies. Seaguy and his faithful fish pal Chubby stumble into a massive conspiracy centering around a new sentient foodstuff called Xoo, Egyptian structures on the moon, the clockwork wasps from the lost city of Atlantis, and sinister entertainment/Big Brother icon Mickey Eye. In other words, it's a typically imaginative work from Morrison, who tosses off inspired ideas left and right as his hapless hero has his eyes opened to the mysterious forces that control the world, only to realize that he didn't really want to know about any of this stuff in the first place. [buy] | [buy]

19. THE BLOT

by Tom Neely, 2007

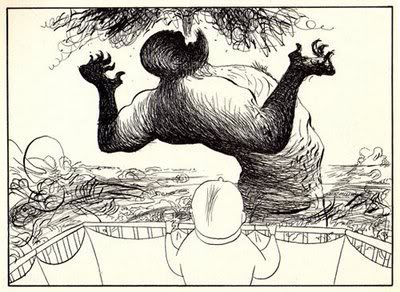

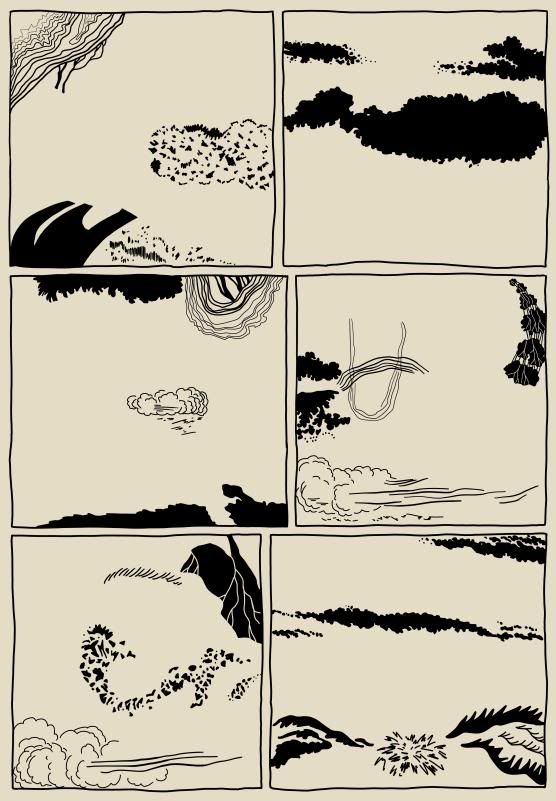

Tom Neely's self-published long-form debut, after a string of minicomics and shorter pieces, is a real shocker, coming out of nowhere to introduce a wholly new and exciting sensibility. His cartoony characters and obtuse symbolism add up to a difficult work, slippery in its meanings and intent, that is nevertheless impossible to look away from. With few words and very little narrative, Neely traces the experiences of a cartoon everyman, with a bulbous, rounded head, comically big feet and Mickey Mouse-style gloves, as he is consumed and pursued by an amorphous black inkblot that sometimes appears as small splotches within his white world, and sometimes threatens to flow across the page, consuming everything in its path. Neely presents various encounters between the man, the blot and a woman who sometimes seems to be helping him and sometimes seems fixed on his destruction. The book deals with conformity, creativity, love and humiliation, all through these enigmatic, nearly silent strips where the blot's seeming meaning and purpose fluidly changes depending on context. [buy]

Tom Neely's self-published long-form debut, after a string of minicomics and shorter pieces, is a real shocker, coming out of nowhere to introduce a wholly new and exciting sensibility. His cartoony characters and obtuse symbolism add up to a difficult work, slippery in its meanings and intent, that is nevertheless impossible to look away from. With few words and very little narrative, Neely traces the experiences of a cartoon everyman, with a bulbous, rounded head, comically big feet and Mickey Mouse-style gloves, as he is consumed and pursued by an amorphous black inkblot that sometimes appears as small splotches within his white world, and sometimes threatens to flow across the page, consuming everything in its path. Neely presents various encounters between the man, the blot and a woman who sometimes seems to be helping him and sometimes seems fixed on his destruction. The book deals with conformity, creativity, love and humiliation, all through these enigmatic, nearly silent strips where the blot's seeming meaning and purpose fluidly changes depending on context. [buy]18. FINDER: DREAM SEQUENCE

by Carla Speed McNeil, 2003

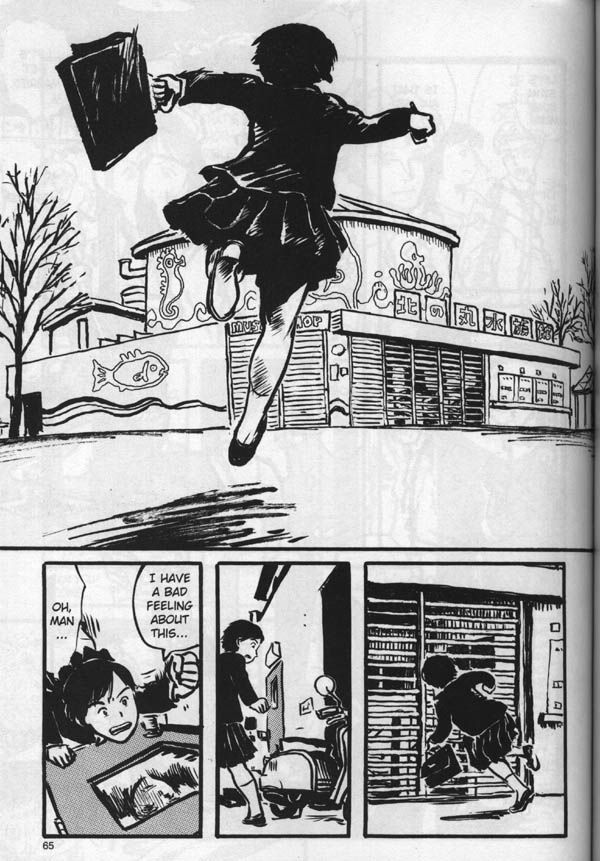

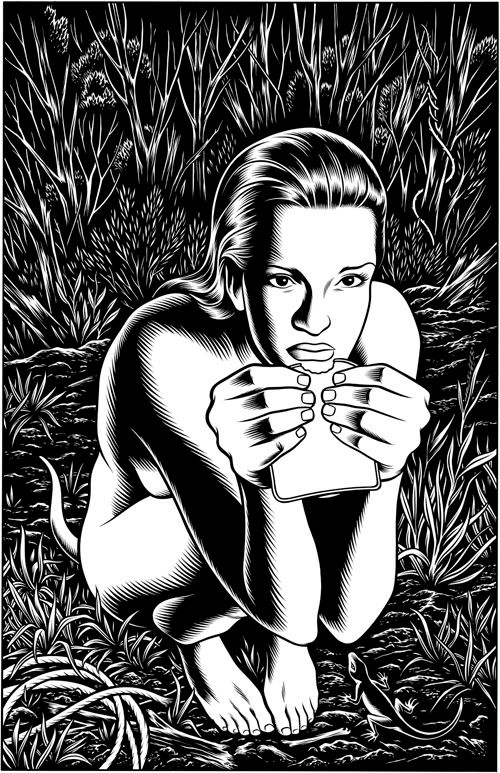

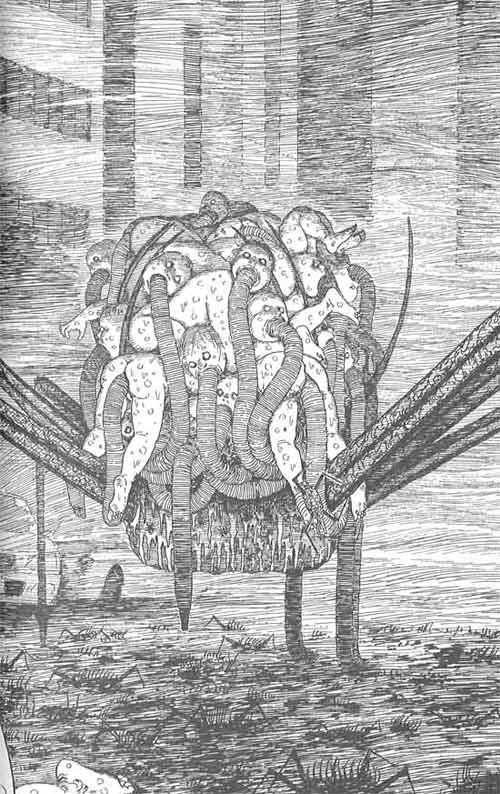

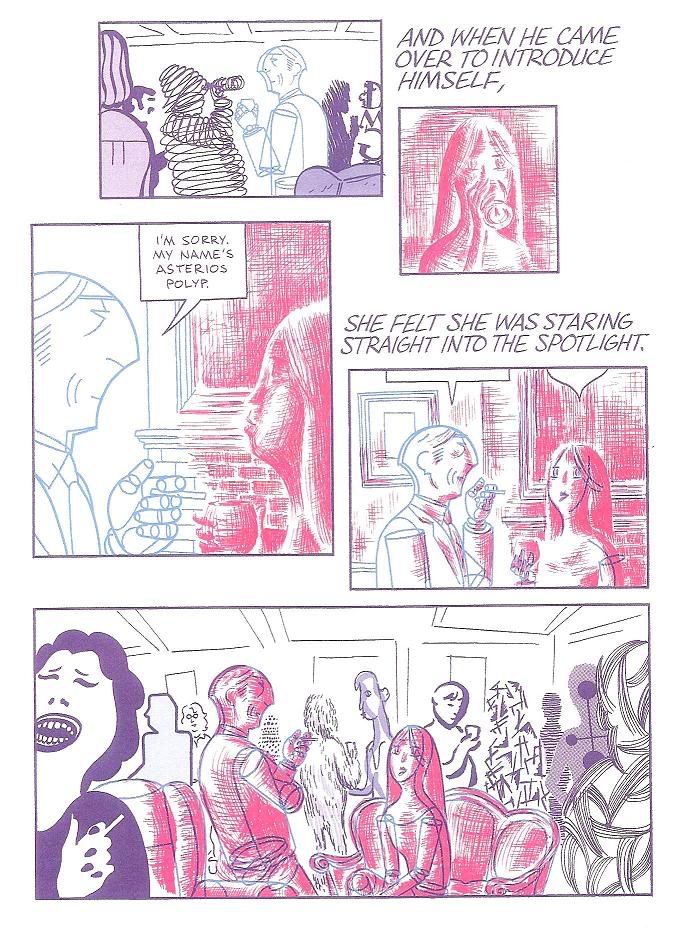

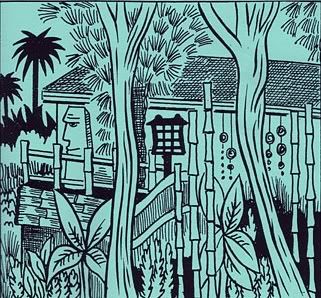

Carla Speed McNeil's Finder is one of the great self-published niche series in comics. Billed as "aboriginal sci-fi," her work involves a richly detailed and complex fantasy world, populated with mythic creatures and humans coexisting within isolated and crumbling domed cities. Her style is utterly distinctive and fresh, with a slight sketchiness that belies the precision of her line and her compositions. She experiments restlessly with page design, and frequently comes up with innovative ways of depicting the unconventional concepts at the core of her work. Her artwork has also improved massively over the years; compare the early, scratchy Sin Eater to the sumptuousness of Dream Sequence, her best book so far, and the difference is obvious. McNeil has matured into one of modern comics' most overlooked stylists. Her expressive line delineates instantly recognizable characters who weave in and out of her storiesin unexpected ways. In Dream Sequence, her usual hero, the rugged wanderer Jaeger, steps out of the center, though he does crop up in the form of various doppelgangers and avatars. Instead, this dense, beautiful work tells the story of a man whose imagination is so powerful that he houses an entire elaborate, three-dimensional world inside his mind, allowing other people to plug in and experience this place like characters in a video game. On one level, McNeil's story is a sci-fi horror piece about a monster set loose within this imaginary Eden, but these genre touches only serve to accentuate the themes and emotions at the story's core: imagination versus reality, creativity, the perils of connecting and forming relationships with other people. This book boasts some of McNeil's most startling and gorgeous imagery, married to one of her best stories. And since her Finder books really have no set order, instead linking together in more oblique, non-linear ways, it's even a good introduction to her work or a standalone read in itself. [buy]

Carla Speed McNeil's Finder is one of the great self-published niche series in comics. Billed as "aboriginal sci-fi," her work involves a richly detailed and complex fantasy world, populated with mythic creatures and humans coexisting within isolated and crumbling domed cities. Her style is utterly distinctive and fresh, with a slight sketchiness that belies the precision of her line and her compositions. She experiments restlessly with page design, and frequently comes up with innovative ways of depicting the unconventional concepts at the core of her work. Her artwork has also improved massively over the years; compare the early, scratchy Sin Eater to the sumptuousness of Dream Sequence, her best book so far, and the difference is obvious. McNeil has matured into one of modern comics' most overlooked stylists. Her expressive line delineates instantly recognizable characters who weave in and out of her storiesin unexpected ways. In Dream Sequence, her usual hero, the rugged wanderer Jaeger, steps out of the center, though he does crop up in the form of various doppelgangers and avatars. Instead, this dense, beautiful work tells the story of a man whose imagination is so powerful that he houses an entire elaborate, three-dimensional world inside his mind, allowing other people to plug in and experience this place like characters in a video game. On one level, McNeil's story is a sci-fi horror piece about a monster set loose within this imaginary Eden, but these genre touches only serve to accentuate the themes and emotions at the story's core: imagination versus reality, creativity, the perils of connecting and forming relationships with other people. This book boasts some of McNeil's most startling and gorgeous imagery, married to one of her best stories. And since her Finder books really have no set order, instead linking together in more oblique, non-linear ways, it's even a good introduction to her work or a standalone read in itself. [buy]17. NINJA

by Brian Chippendale, 2006

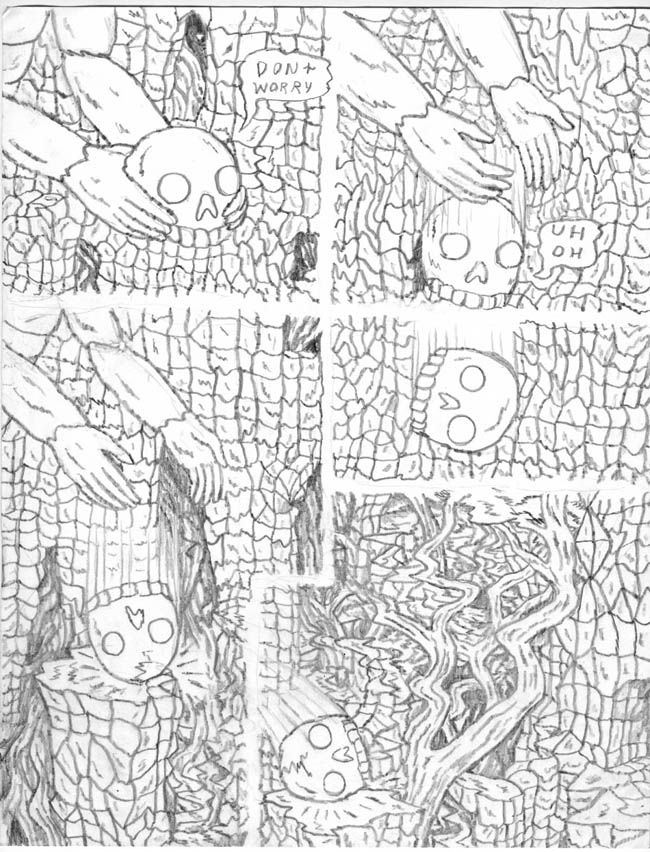

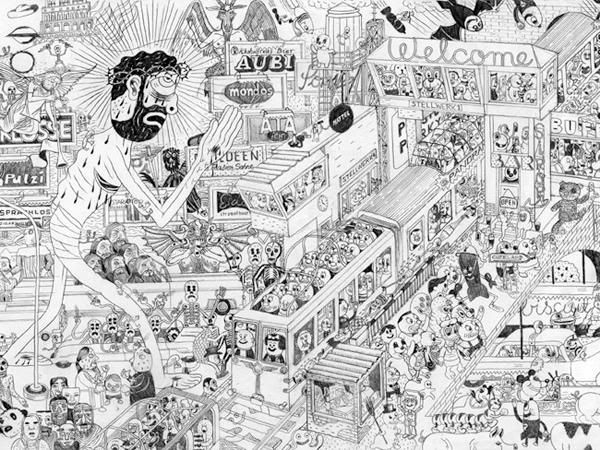

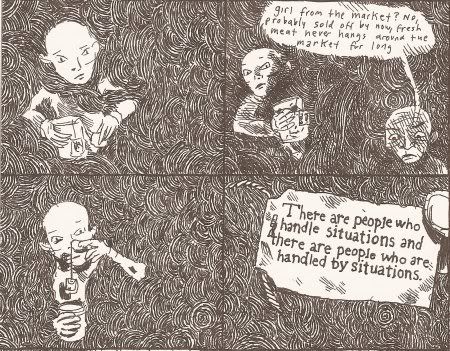

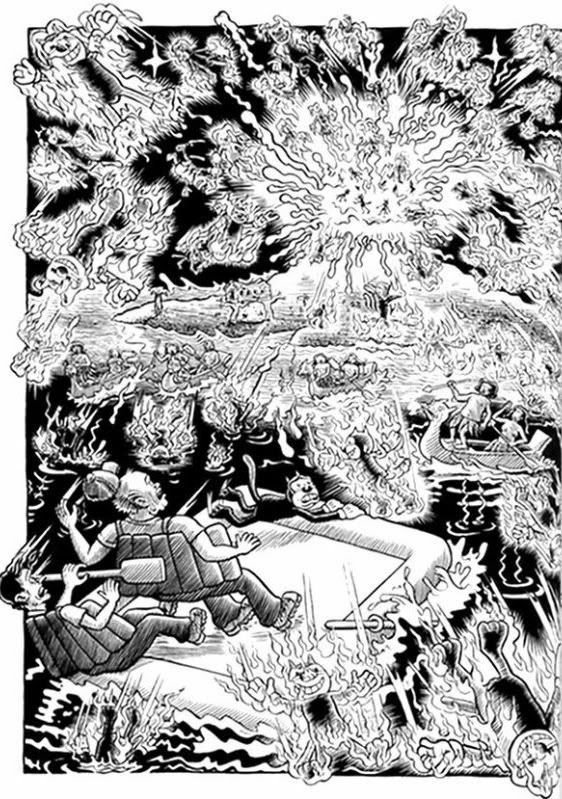

It's often been said of Lightning Bolt drummer Brian Chippendale that he draws like he drums: fast and finicky, filling every inch of available space with the sheer overwhelming density of his creativity. Whether he's pounding on his skins or scratching out dense worlds in ink, Chippendale is a nearly terrifying force. Ninja is the culmination of his work in comics thus far, a massive volume in which the artist picks up where he left off with the crude ninja stories he drew as a young boy — actually included here as the first section of the book — by expanding this ninja's adventures into a grand epic about community and corporate greed. Like many of the artists associated with the loosely defined Fort Thunder scene, Chippendale is fascinated by world-building, by creating whole alternate societies with complex histories and tangled character relationships. This kind of stuff is merely suggested in the sprawling, elliptical Ninja, in which each oversized page is a new "episode" and often follows an entirely new character or set of characters. There's a lot going on here, both in terms of the twisty, tough-to-follow narrative and the dense texture of Chippendale's drawings. The book's all about corporate forces taking over a small town and transforming it; Chippendale, who with the rest of Fort Thunder often lived the lifestyle of a squatters' commune, is very sensitive to the issues involved in gentrification, in forming tight-knit local communities, and in the ways people can be broken apart by powerful outside forces. Ninja is often just a fun, funny action book, and sometimes verges into near-abstract flights of fancy, but it's also politically engaged in very deep ways, particularly in one stunning two-page sequence where Chippendale implicitly compares the passionate, communicative joys of sex to the anti-human evils of government-mandated torture. [buy]

It's often been said of Lightning Bolt drummer Brian Chippendale that he draws like he drums: fast and finicky, filling every inch of available space with the sheer overwhelming density of his creativity. Whether he's pounding on his skins or scratching out dense worlds in ink, Chippendale is a nearly terrifying force. Ninja is the culmination of his work in comics thus far, a massive volume in which the artist picks up where he left off with the crude ninja stories he drew as a young boy — actually included here as the first section of the book — by expanding this ninja's adventures into a grand epic about community and corporate greed. Like many of the artists associated with the loosely defined Fort Thunder scene, Chippendale is fascinated by world-building, by creating whole alternate societies with complex histories and tangled character relationships. This kind of stuff is merely suggested in the sprawling, elliptical Ninja, in which each oversized page is a new "episode" and often follows an entirely new character or set of characters. There's a lot going on here, both in terms of the twisty, tough-to-follow narrative and the dense texture of Chippendale's drawings. The book's all about corporate forces taking over a small town and transforming it; Chippendale, who with the rest of Fort Thunder often lived the lifestyle of a squatters' commune, is very sensitive to the issues involved in gentrification, in forming tight-knit local communities, and in the ways people can be broken apart by powerful outside forces. Ninja is often just a fun, funny action book, and sometimes verges into near-abstract flights of fancy, but it's also politically engaged in very deep ways, particularly in one stunning two-page sequence where Chippendale implicitly compares the passionate, communicative joys of sex to the anti-human evils of government-mandated torture. [buy]16. THE LUTE STRING

by Jim Woodring, 2005

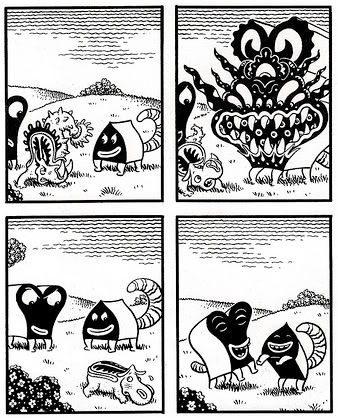

Jim Woodring has long been one of comics' most fascinating and idiosyncratic artists, mostly working, in recent years, within the self-contained universe of his Frank comics. The Lute String, originally published as a standalone book in Japan, is Woodring's most sustained Frank story of recent years, though Frank himself (the amorphously anthropomorphic hero of many Woodring sagas) is only a peripheral figure here. Instead, the focus is on Frank's friends, Pupshaw and Pushpaw, both of whom somehow look like a fusion between a puppy and a small cottage. Like all of Woodring's Frank comics, this one is wordless, and its meaning ambiguous: these stories are like abstract parables, teaching moral lessons through Woodring's selfish, curious, mystically oriented characters. In this case, the moral seems to be: no matter how important, how powerful, you think you are there's always something greater, always someone or some force beyond your control. It's about life as a hierarchy stretching up into some infinite unknowable place. Just as Frank playfully intervenes in the struggle (or mating rite?) between two miniature insect-like creatures, and Pupshaw and Pushpaw delight in terrifying a little morphing hippopotamus, an elephant-like deity eventually intervenes into their plane of reality, sending the two pups off into a strange, frightening alternate dimension: our own world. While there, the two "dogs" wind up mutually scaring and scared by a pair of human children and a songbird, before they're brought back to their own world, newly appreciative of its special wonders and pleasures. All of this is conveyed without words, with Woodring's stylish, detailed imagery and distinctive wiggly hatching. It's moving, funny, and as with all of Woodring's work it demands a close reading. [buy]

Jim Woodring has long been one of comics' most fascinating and idiosyncratic artists, mostly working, in recent years, within the self-contained universe of his Frank comics. The Lute String, originally published as a standalone book in Japan, is Woodring's most sustained Frank story of recent years, though Frank himself (the amorphously anthropomorphic hero of many Woodring sagas) is only a peripheral figure here. Instead, the focus is on Frank's friends, Pupshaw and Pushpaw, both of whom somehow look like a fusion between a puppy and a small cottage. Like all of Woodring's Frank comics, this one is wordless, and its meaning ambiguous: these stories are like abstract parables, teaching moral lessons through Woodring's selfish, curious, mystically oriented characters. In this case, the moral seems to be: no matter how important, how powerful, you think you are there's always something greater, always someone or some force beyond your control. It's about life as a hierarchy stretching up into some infinite unknowable place. Just as Frank playfully intervenes in the struggle (or mating rite?) between two miniature insect-like creatures, and Pupshaw and Pushpaw delight in terrifying a little morphing hippopotamus, an elephant-like deity eventually intervenes into their plane of reality, sending the two pups off into a strange, frightening alternate dimension: our own world. While there, the two "dogs" wind up mutually scaring and scared by a pair of human children and a songbird, before they're brought back to their own world, newly appreciative of its special wonders and pleasures. All of this is conveyed without words, with Woodring's stylish, detailed imagery and distinctive wiggly hatching. It's moving, funny, and as with all of Woodring's work it demands a close reading. [buy]15. ACHEWOOD

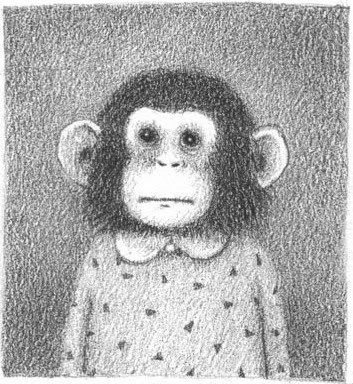

by Chris Onstad, 2001-ongoing

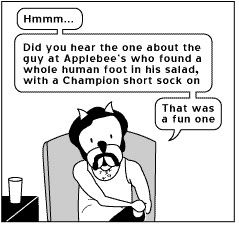

Achewood is one of the greatest, funniest strips to emerge from the 00s boom in webcomics, as comic strip creators began turning to the Internet rather than the dwindling newspaper comic venue. The appeal of Onstad's work is difficult to explain: there's some kind of strange synergy that occurs from the intersection of Onstad's character-based humor, absurd surrealism, minimalist drawing and at times surprising pathos. Achewood started as a Dadaist gag-a-day strip involving a cast of stuffed animals (its first strip literally makes no sense and is somehow funny anyway), and over the years has developed into something much more complex. For one thing, Onstad introduced the characters of three talking cats, most notably the clinically depressive computer programmer Roast Beef and the self-absorbed entrepreneur Ray Smuckles, two characters who have come to occupy the strip's emotional and comedic center. Onstad's work over the years has ranged from surreal "magical realist" arcs, to comedic/dramatic character-based pieces, to parodies of data flow charts, to occasional returns to the strip's roots in one-off gags. [read free] | [buy] | [buy]

Achewood is one of the greatest, funniest strips to emerge from the 00s boom in webcomics, as comic strip creators began turning to the Internet rather than the dwindling newspaper comic venue. The appeal of Onstad's work is difficult to explain: there's some kind of strange synergy that occurs from the intersection of Onstad's character-based humor, absurd surrealism, minimalist drawing and at times surprising pathos. Achewood started as a Dadaist gag-a-day strip involving a cast of stuffed animals (its first strip literally makes no sense and is somehow funny anyway), and over the years has developed into something much more complex. For one thing, Onstad introduced the characters of three talking cats, most notably the clinically depressive computer programmer Roast Beef and the self-absorbed entrepreneur Ray Smuckles, two characters who have come to occupy the strip's emotional and comedic center. Onstad's work over the years has ranged from surreal "magical realist" arcs, to comedic/dramatic character-based pieces, to parodies of data flow charts, to occasional returns to the strip's roots in one-off gags. [read free] | [buy] | [buy]14. PROMETHEA

by Alan Moore, J.H. Williams III, Mick Gray et al, 1999-2005

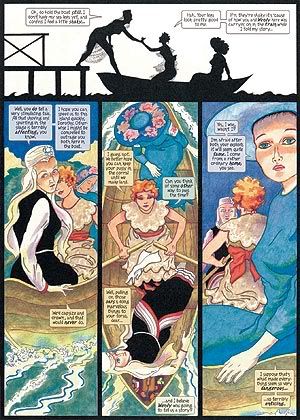

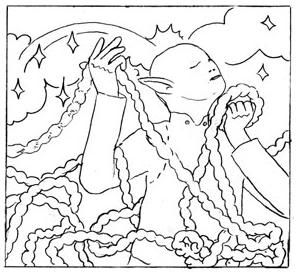

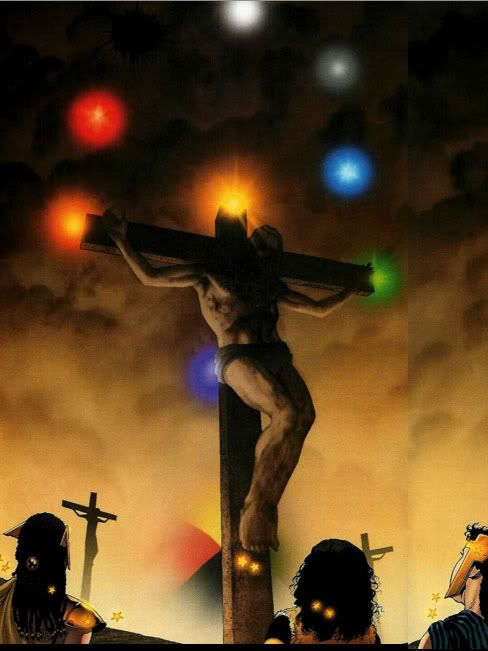

Alan Moore's Promethea, the crown jewel in his America's Best Comics line, starts with an archetypal superhero origin story: an ordinary young girl named Sophie Bangs is forced to take on the mantle of the superheroine/deity Promethea, though she barely understands what's happening to her. It had the makings of another of Moore's lighter works, playfully toying with genre and clichés in the context of a conventionally satisfying narrative. Instead, Moore pulled the rug out from under reader expectations by transforming the book into a high-concept primer on his magical beliefs, a comprehensive illustrated text book on mysticism, magic and spirituality in all its forms. Over the course of an extended odyssey through a series of magical realms — where each issue was color-coded and drawn in a distinct style by the multitalented J.H. Williams III — Moore's heroine took on the role of Dante's Virgil, as a tour guide through the realms of the unknown and the unknowable. Along the way, the journey encompasses the Tarot, magical sexuality and tantra, and the search for the highest states of being. The book is dense and, ultimately, apocalyptic, though for Moore even the apocalypse is both spiritual and necessary, a way of wiping the slate clean and starting fresh in a new, more enlightened and aware world. Promethea is beautiful and exhausting in roughly equal measures, adding up to one of Moore's most challenging and multi-layered works. [buy] | [buy] | [buy] | [buy] | [buy]

Alan Moore's Promethea, the crown jewel in his America's Best Comics line, starts with an archetypal superhero origin story: an ordinary young girl named Sophie Bangs is forced to take on the mantle of the superheroine/deity Promethea, though she barely understands what's happening to her. It had the makings of another of Moore's lighter works, playfully toying with genre and clichés in the context of a conventionally satisfying narrative. Instead, Moore pulled the rug out from under reader expectations by transforming the book into a high-concept primer on his magical beliefs, a comprehensive illustrated text book on mysticism, magic and spirituality in all its forms. Over the course of an extended odyssey through a series of magical realms — where each issue was color-coded and drawn in a distinct style by the multitalented J.H. Williams III — Moore's heroine took on the role of Dante's Virgil, as a tour guide through the realms of the unknown and the unknowable. Along the way, the journey encompasses the Tarot, magical sexuality and tantra, and the search for the highest states of being. The book is dense and, ultimately, apocalyptic, though for Moore even the apocalypse is both spiritual and necessary, a way of wiping the slate clean and starting fresh in a new, more enlightened and aware world. Promethea is beautiful and exhausting in roughly equal measures, adding up to one of Moore's most challenging and multi-layered works. [buy] | [buy] | [buy] | [buy] | [buy]13. ALIAS THE CAT

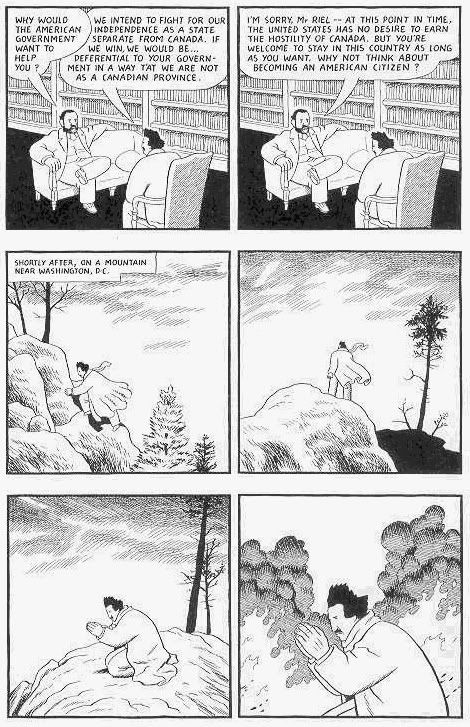

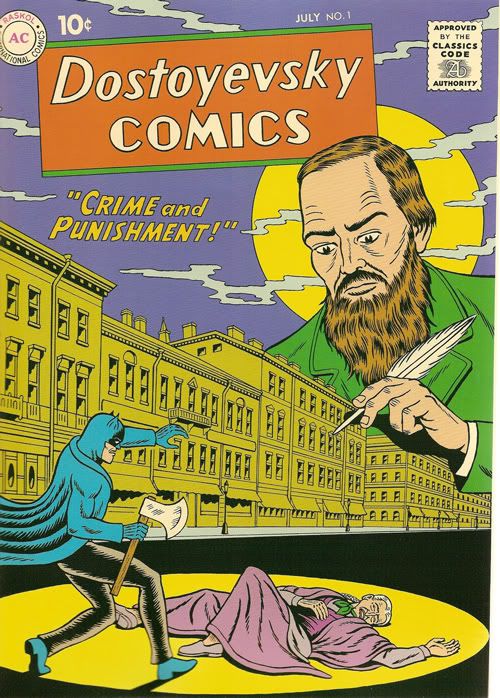

by Kim Deitch, 2002-2005

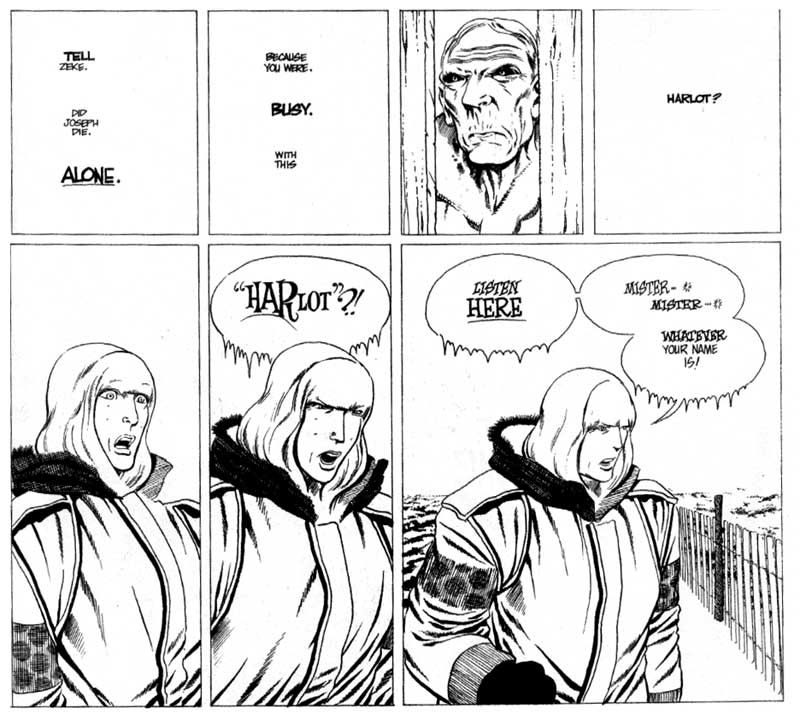

Alias the Cat, originally published as the three-issue miniseries The Stuff of Dreams, is Kim Deitch's best and most sustained treatment of the themes and characters that have fascinated him throughout his career. His work, seen as a whole, is a dense patchwork in which various animators, artists, imaginary/demonic cats, sexual deviants, psychotics, circus performers, midgets and collectors intersect and interact in various ways. For Deitch, the past and the present flow together to tell multi-generational stories that are utterly absurd and yet acquire a strange plausibility through Deitch's matter-of-fact way of combining the real history of art and ephemera with his outrageous tales. In this latest narrative, his eternal muse/antagonist Waldo the Cat returns as a plush doll, a malevolent island deity, and the possible inspiration for a caped crusader who dresses up like a cat. The story features a trip to Midgetville, the discovery of a hitherto unknown newspaper serial, and an exposé on the sexual antics of furries. It's funny, goofy, exciting and far-ranging in its imaginative nonsense accumulations, and throughout it all Deitch's fond sense of nostalgia for a world that never quite was lends emotional heft to the story's elaborate twists and turns. [buy]

Alias the Cat, originally published as the three-issue miniseries The Stuff of Dreams, is Kim Deitch's best and most sustained treatment of the themes and characters that have fascinated him throughout his career. His work, seen as a whole, is a dense patchwork in which various animators, artists, imaginary/demonic cats, sexual deviants, psychotics, circus performers, midgets and collectors intersect and interact in various ways. For Deitch, the past and the present flow together to tell multi-generational stories that are utterly absurd and yet acquire a strange plausibility through Deitch's matter-of-fact way of combining the real history of art and ephemera with his outrageous tales. In this latest narrative, his eternal muse/antagonist Waldo the Cat returns as a plush doll, a malevolent island deity, and the possible inspiration for a caped crusader who dresses up like a cat. The story features a trip to Midgetville, the discovery of a hitherto unknown newspaper serial, and an exposé on the sexual antics of furries. It's funny, goofy, exciting and far-ranging in its imaginative nonsense accumulations, and throughout it all Deitch's fond sense of nostalgia for a world that never quite was lends emotional heft to the story's elaborate twists and turns. [buy]12. BOTTOMLESS BELLY BUTTON/MOME SHORT STORIES

by Dash Shaw, 2008-2009

Dash Shaw is an utterly brilliant young cartoonist who has, in a few short years, advanced from the academic experiments of his earlier work (like the promising Goddess Head) into a formalist genius whose skills encompass both a natural gift for color and a feel for subtle, indirect characterization. Bottomless Belly Button is a daring, daunting work, a 700+ page tome about a mildly dysfunctional family; the book captures the particular moment when the family's parents call together their three grown-up children to announce their divorce. Shaw applies a barrage of formal techniques and styles to documenting the disparate reactions of these characters to the situation, evoking emotions through the sheer force of his drawing rather than stating them outright. His effects are both nakedly symbolic and yet somehow supple, like the way he draws the family's youngest son with the head of a frog, only revealing the meaning of this otherwise unexplained device in a brief, elegant sequence and then continuing to use it to reveal the character's essence throughout the rest of the book.

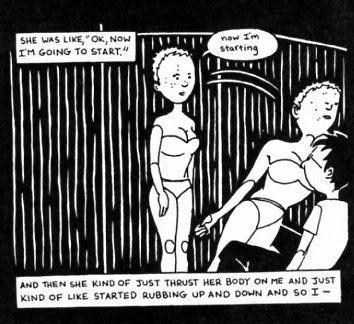

Dash Shaw is an utterly brilliant young cartoonist who has, in a few short years, advanced from the academic experiments of his earlier work (like the promising Goddess Head) into a formalist genius whose skills encompass both a natural gift for color and a feel for subtle, indirect characterization. Bottomless Belly Button is a daring, daunting work, a 700+ page tome about a mildly dysfunctional family; the book captures the particular moment when the family's parents call together their three grown-up children to announce their divorce. Shaw applies a barrage of formal techniques and styles to documenting the disparate reactions of these characters to the situation, evoking emotions through the sheer force of his drawing rather than stating them outright. His effects are both nakedly symbolic and yet somehow supple, like the way he draws the family's youngest son with the head of a frog, only revealing the meaning of this otherwise unexplained device in a brief, elegant sequence and then continuing to use it to reveal the character's essence throughout the rest of the book. Shaw's other great body of work during the 2000s, other than his recently completed and soon-to-be collected online strip Bodyworld, are the short stories he's written for the MOME anthology. These stories mostly utilize science fiction tropes and exploit Shaw's animation cel-inspired color overlays. In each story, color is intimately connected with form and narrative, so that the meaning of the story is communicated through the use of color. A recent piece strips down an episode of the TV show Blind Date by filtering the figures in a greenish haze, revealing unexpected depths of longing and sadness in this televised search for love. In "Satellite CMYK," the title refers to a four-color printing process, and Shaw color-codes four separate layers of reality in a story about spies attempting to move between levels in a strictly segregated society; when he integrates all four colors at last for the final image, it's appropriately stunning. Similarly, in "Look Forward, First Son of Terra Two," two reality streams, one running forwards and the other in reverse, intersect, as Shaw delineates the different timelines with different colors. [buy] | [buy]

11. ALEC/THE FATE OF THE ARTIST

by Eddie Campbell, 2000-2002/2006

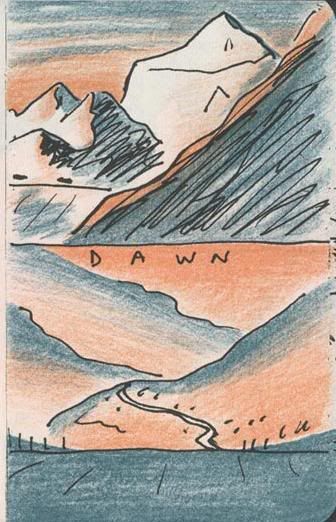

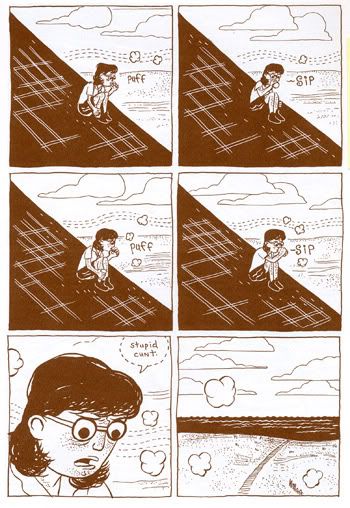

Eddie Campbell's Alec MacGarry is his longtime autobiographical stand-in, created in the late 70s and subsequently worked into numerous graphic novels, short strips and comics over the years. Alec has evolved into a rambling autobiographical opus, composed from a patchwork of anecdotes, jokes, formalist diversions and stories about drinking, family life, artistic creation and everything else that passes through Campbell's witty, tirelessly active mind. The entirety of Campbell's Alec comics, recently collected into a massive tome (which includes several long-form stories, and parts of stories, written and assembled during the 00s) represents one of the great sustained efforts at autobiography, since Campbell's mix of in-the-moment diaristic scribblings and retrospective analysis lend themselves to a multi-faceted view of a life in all its complexity and contradictions. Campbell's sharp sense of humor and observation are also evident in the standalone volume The Fate of the Artist, which is closely related to his Alec MacGarry stories even if the protagonist isn't named as such. It's one of Campbell's most formally ambitious books, an imaginative look at the disappearance of an artist (namely Campbell himself) using a dazzling variety of formal techniques and styles. Campbell incorporates mock comic strips, fumetti (starring his own real-life daughter cracking wise about dear old dad), and numerous metafictional diversions, but the star of the show is the way he combines his familiar scratchy style with a gorgeous but equally ephemeral use of watery, hazy colors. [buy] | [buy]

Eddie Campbell's Alec MacGarry is his longtime autobiographical stand-in, created in the late 70s and subsequently worked into numerous graphic novels, short strips and comics over the years. Alec has evolved into a rambling autobiographical opus, composed from a patchwork of anecdotes, jokes, formalist diversions and stories about drinking, family life, artistic creation and everything else that passes through Campbell's witty, tirelessly active mind. The entirety of Campbell's Alec comics, recently collected into a massive tome (which includes several long-form stories, and parts of stories, written and assembled during the 00s) represents one of the great sustained efforts at autobiography, since Campbell's mix of in-the-moment diaristic scribblings and retrospective analysis lend themselves to a multi-faceted view of a life in all its complexity and contradictions. Campbell's sharp sense of humor and observation are also evident in the standalone volume The Fate of the Artist, which is closely related to his Alec MacGarry stories even if the protagonist isn't named as such. It's one of Campbell's most formally ambitious books, an imaginative look at the disappearance of an artist (namely Campbell himself) using a dazzling variety of formal techniques and styles. Campbell incorporates mock comic strips, fumetti (starring his own real-life daughter cracking wise about dear old dad), and numerous metafictional diversions, but the star of the show is the way he combines his familiar scratchy style with a gorgeous but equally ephemeral use of watery, hazy colors. [buy] | [buy]10. MARY-LAND

by Mary Fleener, 2002-ongoing

Mary Fleener was an important part of the alternative comics scene of the 90s, publishing her series Slutburger and contributing to numerous anthologies. She was never the most famous name, but she was one of the best, with a distinctive Cubism-influenced style and a warm, slightly naughty sense of humor. One could be forgiven for thinking she has since forsaken comics, though in fact she's been steadily producing work throughout the 00s, mostly outside of the normal indie comics channels. Since 2002, she's been publishing her comic strip Mary-Land in the Surf City Times newspaper in her hometown of Encinitas, California. These strips represent an amazing body of work, marrying Fleener's distinctive style and sensibility to content that is provincial, local and domestic. She ruminates on mailbox art, on surfing, on local issues like the fight to preserve public parks, on bicycles, pets, garden pests, and more. Her work in these strips is almost always tied to the specific place she's writing about and the audience she's writing for. It is rare these days, outside of the generic "humor" of newspaper comics, to find comics written, not for a niche audience of comics fans, but for a general audience interested in a wide variety of issues and ideas. Fleener's work nods back to a time when comics weren't confined to a small core audience but were broadcast far and wide to everyone; within her particular geographic area, Fleener's comics aspire to that same generality, that intimate engagement with the everyday world. These comics are refreshingly direct and accessible without ever forsaking the stylistic adventurousness of Fleener's best work. They represent one of our finest cartoonists continuing to work outside of the usual formats and audiences, and producing some of her best, richest work in the process, mostly out of public view for those not living in Encinitas. Fortunately, for the rest of us she's collected a generous sampling of this work in two volumes, available from her website. [buy]

Mary Fleener was an important part of the alternative comics scene of the 90s, publishing her series Slutburger and contributing to numerous anthologies. She was never the most famous name, but she was one of the best, with a distinctive Cubism-influenced style and a warm, slightly naughty sense of humor. One could be forgiven for thinking she has since forsaken comics, though in fact she's been steadily producing work throughout the 00s, mostly outside of the normal indie comics channels. Since 2002, she's been publishing her comic strip Mary-Land in the Surf City Times newspaper in her hometown of Encinitas, California. These strips represent an amazing body of work, marrying Fleener's distinctive style and sensibility to content that is provincial, local and domestic. She ruminates on mailbox art, on surfing, on local issues like the fight to preserve public parks, on bicycles, pets, garden pests, and more. Her work in these strips is almost always tied to the specific place she's writing about and the audience she's writing for. It is rare these days, outside of the generic "humor" of newspaper comics, to find comics written, not for a niche audience of comics fans, but for a general audience interested in a wide variety of issues and ideas. Fleener's work nods back to a time when comics weren't confined to a small core audience but were broadcast far and wide to everyone; within her particular geographic area, Fleener's comics aspire to that same generality, that intimate engagement with the everyday world. These comics are refreshingly direct and accessible without ever forsaking the stylistic adventurousness of Fleener's best work. They represent one of our finest cartoonists continuing to work outside of the usual formats and audiences, and producing some of her best, richest work in the process, mostly out of public view for those not living in Encinitas. Fortunately, for the rest of us she's collected a generous sampling of this work in two volumes, available from her website. [buy]9. X-FORCE/X-STATIX

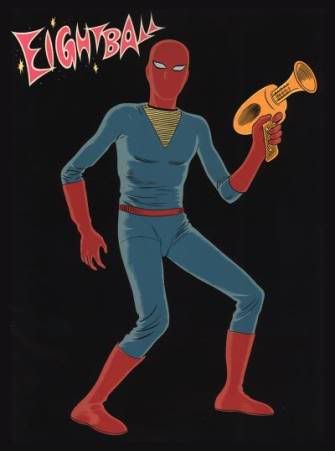

by Peter Milligan & Mike Allred, 2001-2004

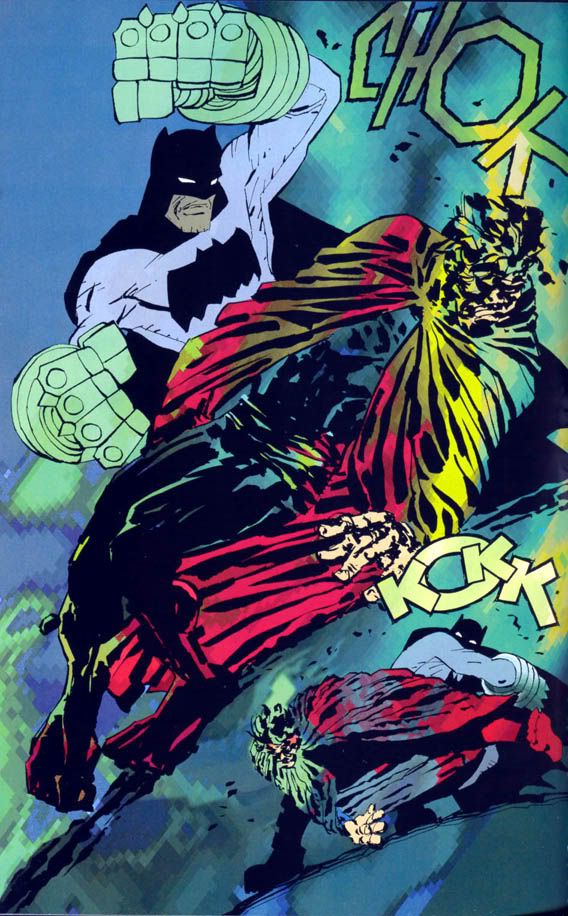

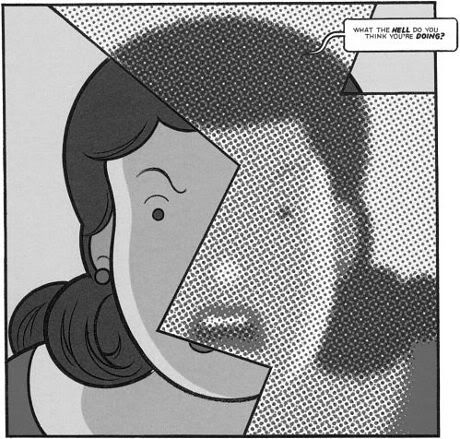

There is perhaps no less likely place to find a great comic than under the banner of X-Force, traditionally the trashiest and stupidest title in Marvel's vast, incestuous X-universe; no mean feat, that. Maybe it was this very disposability, this lack of importance, that allowed writer Peter Milligan, in collaboration with Mike Allred of Madman, to completely re-envision the title, unceremoniously discarding all the familiar characters and crafting a new team, and a new aesthetic, from scratch. This new X-Force is a corporately sponsored superhero team who seem to exist mainly for the purpose of exploiting media and marketing possibilities, though they also have an alarmingly high mortality rate. In fact, in the very first issue of the Milligan/Allred series, the pair introduced a whole team of new heroes, developing their pasts, their powers, their personal issues... only to kill off all but two of them by the last page, including the character who had been primed to be the book's central hero. This destabilizing gesture established the groundwork for what was to come: superhero soap opera wrapped up in media critiques, off-the-wall satire, plenty of blood-and-guts action, and an irreverent approach to the storytelling rulebook. Allred's clean, expressive art, honed by his years of drawing Madman, is at its best here, especially in the infamous and boldly experimental silent issue, starring the group's green, blobby mainstay Doop. The Milligan/Allred X-Force — which eventually rebooted as X-Statix to reflect its distance from the conventional X-universe — is a masterpiece of superhero satire that, eventually, reached its absurdist peak in a battle of finger flicks between a butt-naked Iron Man and equally stripped-down X-Statix leader Mr. Sensitive. It doesn't get any better, or sillier, than that. [buy] | [buy] | [buy] | [buy]

There is perhaps no less likely place to find a great comic than under the banner of X-Force, traditionally the trashiest and stupidest title in Marvel's vast, incestuous X-universe; no mean feat, that. Maybe it was this very disposability, this lack of importance, that allowed writer Peter Milligan, in collaboration with Mike Allred of Madman, to completely re-envision the title, unceremoniously discarding all the familiar characters and crafting a new team, and a new aesthetic, from scratch. This new X-Force is a corporately sponsored superhero team who seem to exist mainly for the purpose of exploiting media and marketing possibilities, though they also have an alarmingly high mortality rate. In fact, in the very first issue of the Milligan/Allred series, the pair introduced a whole team of new heroes, developing their pasts, their powers, their personal issues... only to kill off all but two of them by the last page, including the character who had been primed to be the book's central hero. This destabilizing gesture established the groundwork for what was to come: superhero soap opera wrapped up in media critiques, off-the-wall satire, plenty of blood-and-guts action, and an irreverent approach to the storytelling rulebook. Allred's clean, expressive art, honed by his years of drawing Madman, is at its best here, especially in the infamous and boldly experimental silent issue, starring the group's green, blobby mainstay Doop. The Milligan/Allred X-Force — which eventually rebooted as X-Statix to reflect its distance from the conventional X-universe — is a masterpiece of superhero satire that, eventually, reached its absurdist peak in a battle of finger flicks between a butt-naked Iron Man and equally stripped-down X-Statix leader Mr. Sensitive. It doesn't get any better, or sillier, than that. [buy] | [buy] | [buy] | [buy]8. ACME NOVELTY LIBRARY #18-19

by Chris Ware, 2007-2008

There are few artists who have had as great an impact on modern comics as Chris Ware, whose name is virtually synonymous with the popular explosion of the "graphic novel" in recent years, thanks in large part to his lengthy Jimmy Corrigan tome. He is a formal genius of the first order, doing things with page layouts and the incorporation of text that place him at the forefront of formal experimentation within comics. In recent years, he's split his talent mostly between two new ongoing stories, Rusty Brown and Building Stories. The former promises to be another Jimmy Corrigan-esque time-spanning epic of losers and jerks, and in the nineteenth issue of his ongoing Acme Novelty Library, Ware continued Rusty's story in an unusual way, by weaving back and forth between "reality" and a fictional sci-fi story supposedly written by one of his characters. The flow between these two layers of reality is startlingly complex, in ways that may not be apparent at first blush: key details in the sci-fi story that might be initially puzzling are later revealed to have psychologically telling connections with the writer's own life. One particular throwaway detail even seems like an innocuous printing mistake at first, until Ware slowly unfolds an explanation that makes this small touch devastating.

There are few artists who have had as great an impact on modern comics as Chris Ware, whose name is virtually synonymous with the popular explosion of the "graphic novel" in recent years, thanks in large part to his lengthy Jimmy Corrigan tome. He is a formal genius of the first order, doing things with page layouts and the incorporation of text that place him at the forefront of formal experimentation within comics. In recent years, he's split his talent mostly between two new ongoing stories, Rusty Brown and Building Stories. The former promises to be another Jimmy Corrigan-esque time-spanning epic of losers and jerks, and in the nineteenth issue of his ongoing Acme Novelty Library, Ware continued Rusty's story in an unusual way, by weaving back and forth between "reality" and a fictional sci-fi story supposedly written by one of his characters. The flow between these two layers of reality is startlingly complex, in ways that may not be apparent at first blush: key details in the sci-fi story that might be initially puzzling are later revealed to have psychologically telling connections with the writer's own life. One particular throwaway detail even seems like an innocuous printing mistake at first, until Ware slowly unfolds an explanation that makes this small touch devastating.Ware's other major post-Corrigan project is Building Stories, which has mostly been published as a series of Sunday-style single pages or double-page spreads in various newspapers and anthologies. A lot of this material, building up to another sprawling long-form narrative, has been collected in issue 18 of Acme Novelty Library. At its core is yet another of Ware's sadsack heroes — a lonely woman who's missing a leg — but this is some of the artist's most formally ambitious work. Each of these stories breaks down the page into a massive diagram, often presenting the titular apartment building with the rooms within it as panels, while mazes of arrows and text weave around the page, directing the reader's attention in a non-linear flow. It's daring and inventive work, forcing the reader to discover new ways of reading every time one approaches the page. [buy] | [buy]

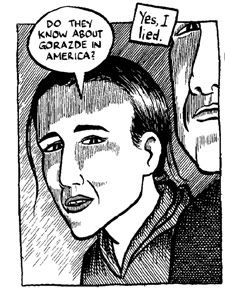

7. SAFE AREA GORAZDE

by Joe Sacco, 2000

Joe Sacco is a unique figure in modern comics: there is no one else who combines sheer cartooning chops with a newspaper reporter's sensibility and instincts in quite the same way. His reportage from war-torn areas of Israel/Palestine and the Balkan region gets to the heart of these conflicts through the testimonies of witnesses and victims, privileging the stories people tell and the experiences of average people on the ground during historic tragedies. While always conscious of the big-picture story, Sacco is committed to a more intimate, personal form of journalism, rooted in oral anecdote and day-to-day life. Safe Area Gorazde is one of his finest works, an account of his time spent in a nominally stable UN-controlled area of Bosnia, where he speaks with survivors and refugees from the Serbian offensive. As in most of Sacco's work, this book weaves together past and present, juxtaposing excerpts from history against the present lives of these people, fenced in and surrounded by devastation on all sides. And yet the book's most poignant current is arguably the way in which normality keeps trying to reassert itself despite the horrors these people have experienced. Little things like music, clothes and cigarettes become loaded signifiers of stability and normality, of the possibility that life will be good again, no longer dictated by terror and death. Even as Sacco explores various horrifying anecdotes of survival and violence, he is also aware that his interviewees are just as concerned with more prosaic struggles: relationships troubled both by the war and more familiar obstacles, the desire for designer clothes from the West, the need to laugh, dance, drink and have fun with friends. This texture, this interplay between horror and normality, makes Safe Area Gorazde an especially powerful document of the effects of war. [buy]

Joe Sacco is a unique figure in modern comics: there is no one else who combines sheer cartooning chops with a newspaper reporter's sensibility and instincts in quite the same way. His reportage from war-torn areas of Israel/Palestine and the Balkan region gets to the heart of these conflicts through the testimonies of witnesses and victims, privileging the stories people tell and the experiences of average people on the ground during historic tragedies. While always conscious of the big-picture story, Sacco is committed to a more intimate, personal form of journalism, rooted in oral anecdote and day-to-day life. Safe Area Gorazde is one of his finest works, an account of his time spent in a nominally stable UN-controlled area of Bosnia, where he speaks with survivors and refugees from the Serbian offensive. As in most of Sacco's work, this book weaves together past and present, juxtaposing excerpts from history against the present lives of these people, fenced in and surrounded by devastation on all sides. And yet the book's most poignant current is arguably the way in which normality keeps trying to reassert itself despite the horrors these people have experienced. Little things like music, clothes and cigarettes become loaded signifiers of stability and normality, of the possibility that life will be good again, no longer dictated by terror and death. Even as Sacco explores various horrifying anecdotes of survival and violence, he is also aware that his interviewees are just as concerned with more prosaic struggles: relationships troubled both by the war and more familiar obstacles, the desire for designer clothes from the West, the need to laugh, dance, drink and have fun with friends. This texture, this interplay between horror and normality, makes Safe Area Gorazde an especially powerful document of the effects of war. [buy]6. ASTHMA

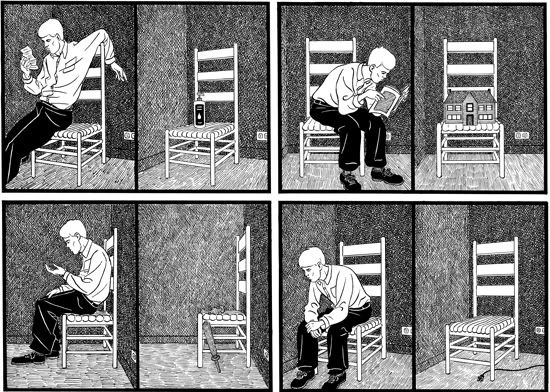

by John Hankiewicz, 2002-2006

The comics of John Hankiewicz, as collected in Asthma, his only full-length collection to date, are poetic and strange, using the language of comics not so much to tell stories as to create moods, to suggest ineffable, inexpressible ideas in the permutations of cartoon iconography and densely cross-hatched drawings. The comics in Asthma cover a wide range of styles and concerns, establishing the relatively broad territory that Hankiewicz explores. His "Amateur Comics" strips wordlessly rearrange a set of simple elements (man, chair, radio, book, picture frame) in ways that suggest abstract visual poetry, repeating motifs and "rhyming" the compositions from panel to panel. In "Martha Gregory," he uses a subtle disconnect between image and narration to explore the psychology of a dissatisfied woman and her male counterpart. Other strips, like the "Dance" series," simply explore the pure aesthetics of movement and form, as stylized, graceful dancers flow together and apart, creating abstract patterns as they move. Hankiewicz's work is frequently puzzling and inscrutable, suggesting slippery, half-formed ideas that are difficult to tease out from within his by turns surreal or mundane compositions. His comics are evasive, never adhering to a single interpretation but instead offering up many suggestive possibilities. [buy]

The comics of John Hankiewicz, as collected in Asthma, his only full-length collection to date, are poetic and strange, using the language of comics not so much to tell stories as to create moods, to suggest ineffable, inexpressible ideas in the permutations of cartoon iconography and densely cross-hatched drawings. The comics in Asthma cover a wide range of styles and concerns, establishing the relatively broad territory that Hankiewicz explores. His "Amateur Comics" strips wordlessly rearrange a set of simple elements (man, chair, radio, book, picture frame) in ways that suggest abstract visual poetry, repeating motifs and "rhyming" the compositions from panel to panel. In "Martha Gregory," he uses a subtle disconnect between image and narration to explore the psychology of a dissatisfied woman and her male counterpart. Other strips, like the "Dance" series," simply explore the pure aesthetics of movement and form, as stylized, graceful dancers flow together and apart, creating abstract patterns as they move. Hankiewicz's work is frequently puzzling and inscrutable, suggesting slippery, half-formed ideas that are difficult to tease out from within his by turns surreal or mundane compositions. His comics are evasive, never adhering to a single interpretation but instead offering up many suggestive possibilities. [buy]5. KRAMERS ERGOT

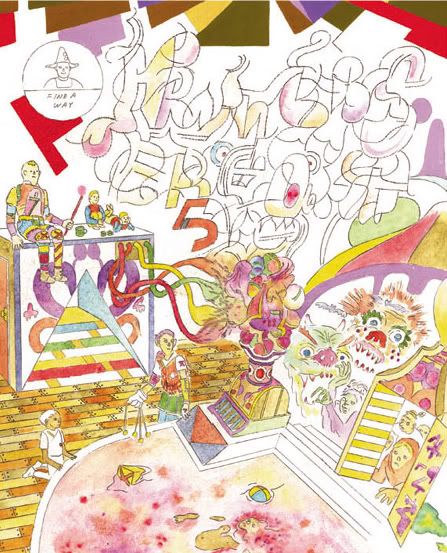

by Sammy Harkham (editor) & various, 2003-2008

The defining anthology of the 2000s has been Sammy Harkham's Kramers Ergot, which started as a small, self-published zine and, with its fourth volume, became the gathering point for everything avant-garde, experimental, unusual and inventive in early 21st Century comics. The fourth, fifth and sixth volumes of this groundbreaking anthology gathered together under one roof a virtual who's who of artists pushing the boundaries of what comics could be. Contributions ranged from the wayward children's book aesthetic of Souther Salazar, to the patient, straightforward storytelling of editor Harkham, to the media collage of Paper Rad, to the brightly colored dream comics of David Heatley, to John Hankiewicz's destabilizing newspaper strip parody, to the delicate minimalism of Anders Nilsen, to the arty innovations of Elvis Studio, and so much more. Along the way, Harkham's increasingly broad survey gathered in more conventional storytellers (including some of the best work done anywhere by either Gabrielle Bell or Kevin Huizenga), reprints of obscure older material from around the world, and excerpts of work in progress from familiar names like Gary Panter, Chris Ware and Jerry Moriarty. Then, with the massive Kramers Ergot 7, proportioned like giant-size classic newspaper strips such as Little Nemo in Slumberland, Harkham's anthology presented a compelling formal challenge to some of comics' best artists, asking them to work on a truly huge canvas. Taken as a whole body of work, these four issues of Kramers Ergot represent one of the most exciting collections of boundary-expanding comics available. [buy] | [buy] | [buy] | [buy]

The defining anthology of the 2000s has been Sammy Harkham's Kramers Ergot, which started as a small, self-published zine and, with its fourth volume, became the gathering point for everything avant-garde, experimental, unusual and inventive in early 21st Century comics. The fourth, fifth and sixth volumes of this groundbreaking anthology gathered together under one roof a virtual who's who of artists pushing the boundaries of what comics could be. Contributions ranged from the wayward children's book aesthetic of Souther Salazar, to the patient, straightforward storytelling of editor Harkham, to the media collage of Paper Rad, to the brightly colored dream comics of David Heatley, to John Hankiewicz's destabilizing newspaper strip parody, to the delicate minimalism of Anders Nilsen, to the arty innovations of Elvis Studio, and so much more. Along the way, Harkham's increasingly broad survey gathered in more conventional storytellers (including some of the best work done anywhere by either Gabrielle Bell or Kevin Huizenga), reprints of obscure older material from around the world, and excerpts of work in progress from familiar names like Gary Panter, Chris Ware and Jerry Moriarty. Then, with the massive Kramers Ergot 7, proportioned like giant-size classic newspaper strips such as Little Nemo in Slumberland, Harkham's anthology presented a compelling formal challenge to some of comics' best artists, asking them to work on a truly huge canvas. Taken as a whole body of work, these four issues of Kramers Ergot represent one of the most exciting collections of boundary-expanding comics available. [buy] | [buy] | [buy] | [buy]4. GANGES/CURSES/OR ELSE

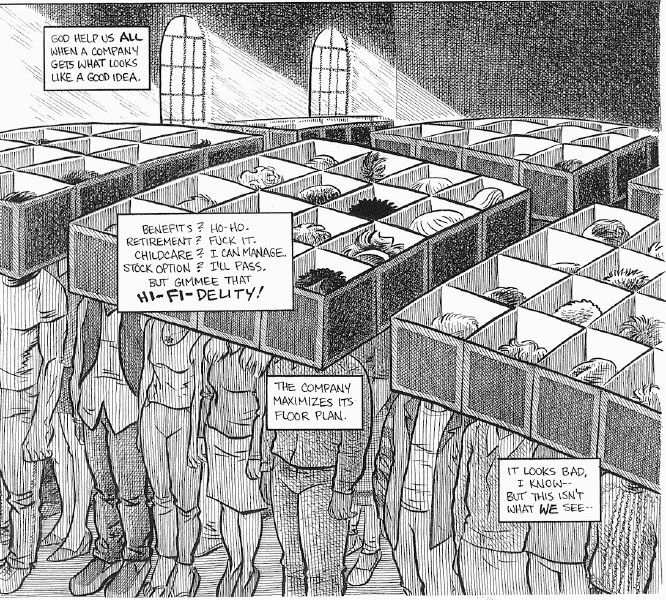

by Kevin Huizenga, 2007-ongoing/2002-2004/2004-2008

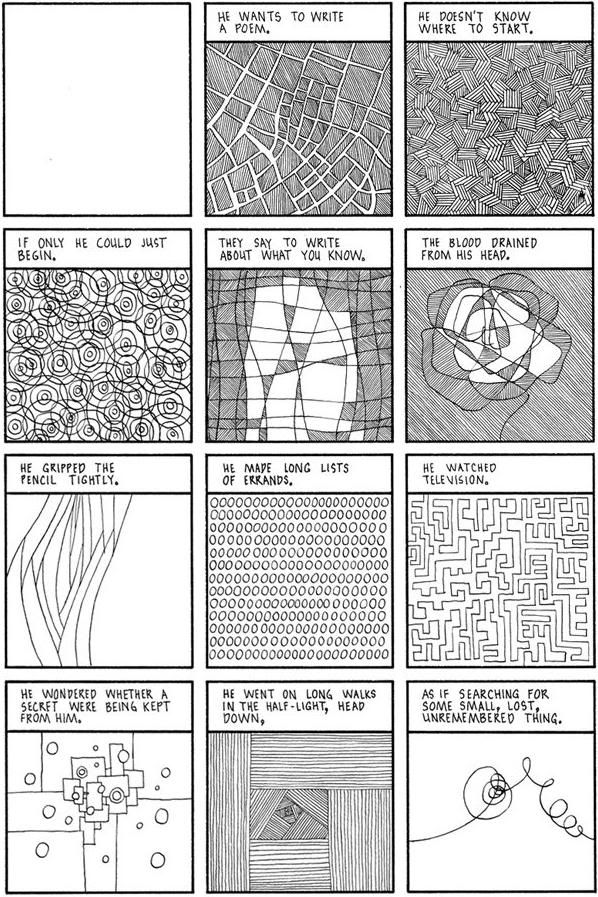

Kevin Huizenga is the best young artist in comics. It's as simple as that. With his recent Fantagraphics series Ganges (part of the Ignatz line of high-quality pamphlets) Huizenga has matured into one of comics' finest formalists. His work here, starring his everyman stand-in Glenn Ganges, is concerned with the minutiae of daily life, which is common enough in indie comics. What sets Huizenga apart is that he deals with such mundanities not only in terms of small external actions and observational details, but with a sensitivity to the complexities of the thought process, of the richness of mental processes and the insistent cycles of memory. His work is deeply introspective, constantly coming up with inventive and expressive ways of visualizing thought: the third issue of Ganges, in which the protagonist spends the better part of 20 pages simply lying in bed thinking, is the apex of this approach, as Ganges wanders through his own mind, interacting with his mental landscape and the words flowing through his head as he tries in vain to clear his mind and go to sleep. It's cerebral in the best sense, treating thought and ideas as visceral and sensory. The series' high point thus far, though, is actually its stunning second issue, which opens with a few pages of abstract permutations, an imaginary video game in which pixelated figures undergo intense transformations as they do battle. This leads into a story where Glenn's experience playing a video game causes him to free-associate to his time as an office drone during the dot-com boom, and the chain of memories unexpectedly creates poignancy and depth from something as simple as playing a shoot-em-up video game. By the end of the story, Huizenga has explored the intricacies of office culture, the economic realities of the Internet age, the sensual and communitarian pleasures of multiplayer online gaming, and the mingled nostalgia and regret implicit in this story about failure and loss. It's all lent extra impact by Huizenga's crisp style, which makes something virtually spiritual out of digital fighters careening across a computer screen.

Kevin Huizenga is the best young artist in comics. It's as simple as that. With his recent Fantagraphics series Ganges (part of the Ignatz line of high-quality pamphlets) Huizenga has matured into one of comics' finest formalists. His work here, starring his everyman stand-in Glenn Ganges, is concerned with the minutiae of daily life, which is common enough in indie comics. What sets Huizenga apart is that he deals with such mundanities not only in terms of small external actions and observational details, but with a sensitivity to the complexities of the thought process, of the richness of mental processes and the insistent cycles of memory. His work is deeply introspective, constantly coming up with inventive and expressive ways of visualizing thought: the third issue of Ganges, in which the protagonist spends the better part of 20 pages simply lying in bed thinking, is the apex of this approach, as Ganges wanders through his own mind, interacting with his mental landscape and the words flowing through his head as he tries in vain to clear his mind and go to sleep. It's cerebral in the best sense, treating thought and ideas as visceral and sensory. The series' high point thus far, though, is actually its stunning second issue, which opens with a few pages of abstract permutations, an imaginary video game in which pixelated figures undergo intense transformations as they do battle. This leads into a story where Glenn's experience playing a video game causes him to free-associate to his time as an office drone during the dot-com boom, and the chain of memories unexpectedly creates poignancy and depth from something as simple as playing a shoot-em-up video game. By the end of the story, Huizenga has explored the intricacies of office culture, the economic realities of the Internet age, the sensual and communitarian pleasures of multiplayer online gaming, and the mingled nostalgia and regret implicit in this story about failure and loss. It's all lent extra impact by Huizenga's crisp style, which makes something virtually spiritual out of digital fighters careening across a computer screen.Huizenga's work in the 2000s hasn't been limited to Ganges, by any means. He's been a prolific and diverse artist, also publishing five issues of the minicomic Or Else, which combined reprints of material from his previous Supermonster series with new stories. He also put together the book collection Curses, which gathered together Or Else #1 with various anthology appearances and short stories. Huizenga's work is best appreciated as a complete oeuvre, as his signature fascinations — the mind, nature, religion, domesticity, memory, philosophy, science — are treated in different ways and different aesthetic forms throughout his work. Glenn Ganges, the blank-faced, big-nosed cartoon who wanders through many of these stories, is Huizenga's neutral observer, his way of getting a handle on all the ideas and moments he wants to explore. His work, no matter where it is encountered, is refreshing, sophisticated and exciting. [buy] | [buy]

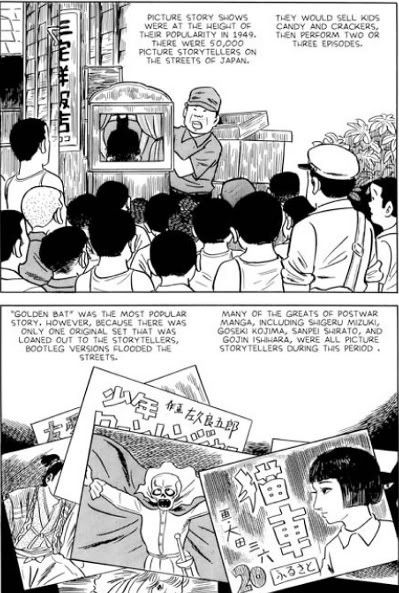

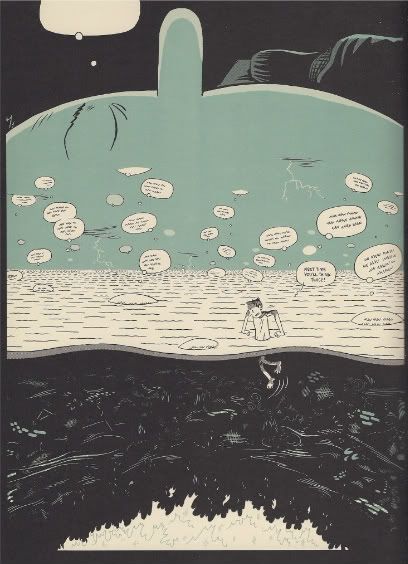

3. NEW ENGINEERING/TRAVEL

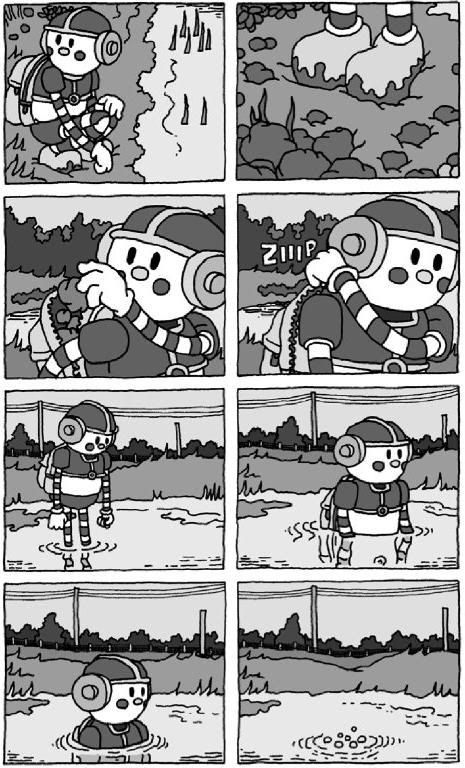

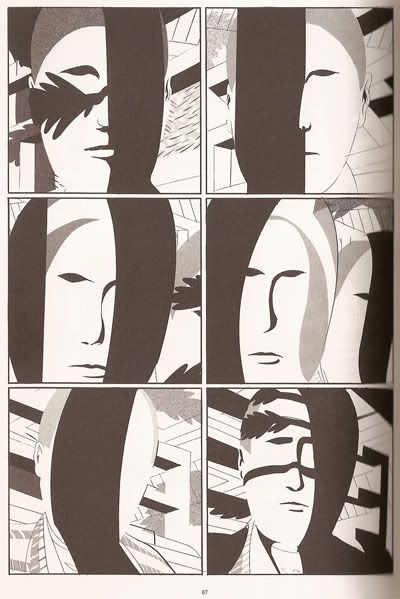

by Yuichi Yokoyama, 2004

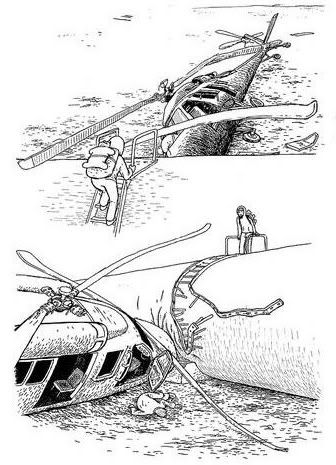

If you have never seen the comics of Yuichi Yokoyama, you have never seen anything like them. The mostly silent, formally restless work of this Japanese innovator is in a category of its own. There have been two Picturebox books collecting his manga output thus far, and both are rewarding, idiosyncratic, and wildly entertaining. New Engineering collects two sets of stories, one of them detailing the construction of various structures of inscrutable purpose, the other examining, in equally dense detail, a series of fights between goofily-dressed warriors. Yokoyama is obsessed with process, with examining a series of actions through the lens of his time-stretched sequences and analytical images. The combat stories are particularly enlightening in this regard, as Yokoyama observes the way his absurdist weapons and fight scenarios — in one, there's a sword so big it requires several men to wield it — cause aesthetically appealing havoc and devastation. In one story, fighters throw books at one another, and Yokoyama precisely analyzes all of the ways in which sword thrusts might slice through and take apart the books. His "Public Works" stories are essentially the reverse of this, examining assembly rather than disassembly, but the observant, witty sensibility is more or less the same.

If you have never seen the comics of Yuichi Yokoyama, you have never seen anything like them. The mostly silent, formally restless work of this Japanese innovator is in a category of its own. There have been two Picturebox books collecting his manga output thus far, and both are rewarding, idiosyncratic, and wildly entertaining. New Engineering collects two sets of stories, one of them detailing the construction of various structures of inscrutable purpose, the other examining, in equally dense detail, a series of fights between goofily-dressed warriors. Yokoyama is obsessed with process, with examining a series of actions through the lens of his time-stretched sequences and analytical images. The combat stories are particularly enlightening in this regard, as Yokoyama observes the way his absurdist weapons and fight scenarios — in one, there's a sword so big it requires several men to wield it — cause aesthetically appealing havoc and devastation. In one story, fighters throw books at one another, and Yokoyama precisely analyzes all of the ways in which sword thrusts might slice through and take apart the books. His "Public Works" stories are essentially the reverse of this, examining assembly rather than disassembly, but the observant, witty sensibility is more or less the same.As good as this book is, it is in some ways dwarfed by the accomplishment of Yokoyama's other collection, Travel, which is quite simply stunning in the way it takes a simple set-up and single-mindedly examines every facet of the experience. The book silently follows several passengers — looking much like the silly heroes of the "Combats" stories — on a lengthy train trip. And that's it. A bunch of guys stride purposefully onto a train, wander through its corridors looking for a seat, gaze absentmindedly out the windows, perhaps plot conspiracies that are never enacted, then disembark at the end. It's all stylized and exaggerated so that every least little action is magnified, and Yokoyama nearly makes an action extravaganza out of the most prosaic material. It is also a book deeply attuned to sensual and sensory experiences, boasting one of the most beautiful sequences in all of comics, when the train passes through a storm and its aftermath, and the play of shadows, and of light reflecting off water, creates a few pages of near-abstract design that has to be seen to be believed. [buy] | [buy]

2. JIMBO IN PURGATORY

by Gary Panter, 2000

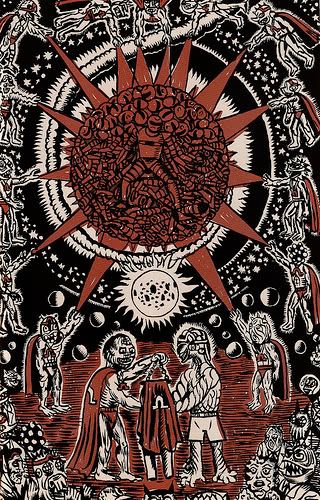

Gary Panter's magnum opus is his epic mash-up of the Purgatory section from Dante's Divine Comedy with Panter's own punk everyman character Jimbo and a wide array of cultural reference points, ranging from Boccaccio's Dante-inspired Decameron to Frank Zappa, John Lennon, 50s sci-fi movies, pin-up models, punk rock, and more. It's a dazzling pastiche, with every page laid out in a tight grid of nine panels, and each panel starting with a quote from Dante and relating it to all sorts of other cultural reference points, images and quotes. The panels don't just stand alone either, but instead form unified patterns and images at the level of the page, so that each page can be read both as a sequence of nine panels and as a single image in itself. The denseness of Panter's references and cross-references makes the experience of reading this book a truly overwhelming experience; every line, every image, spirals into multiple other references and ideas, pulling in the whole wide expanse of world culture as a stomping ground for Jimbo's wanderings through the Purgatory of modern existence towards enlightenment. [buy]

Gary Panter's magnum opus is his epic mash-up of the Purgatory section from Dante's Divine Comedy with Panter's own punk everyman character Jimbo and a wide array of cultural reference points, ranging from Boccaccio's Dante-inspired Decameron to Frank Zappa, John Lennon, 50s sci-fi movies, pin-up models, punk rock, and more. It's a dazzling pastiche, with every page laid out in a tight grid of nine panels, and each panel starting with a quote from Dante and relating it to all sorts of other cultural reference points, images and quotes. The panels don't just stand alone either, but instead form unified patterns and images at the level of the page, so that each page can be read both as a sequence of nine panels and as a single image in itself. The denseness of Panter's references and cross-references makes the experience of reading this book a truly overwhelming experience; every line, every image, spirals into multiple other references and ideas, pulling in the whole wide expanse of world culture as a stomping ground for Jimbo's wanderings through the Purgatory of modern existence towards enlightenment. [buy]1. LOVE AND ROCKETS VOL. II

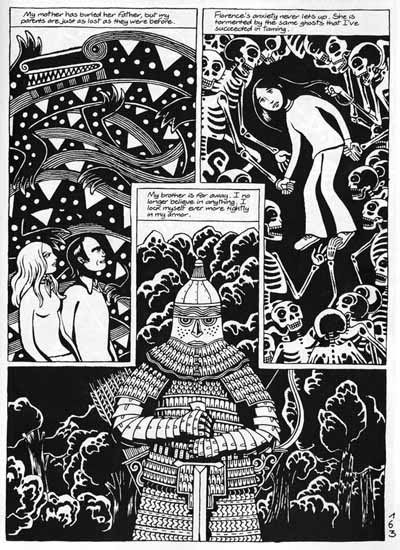

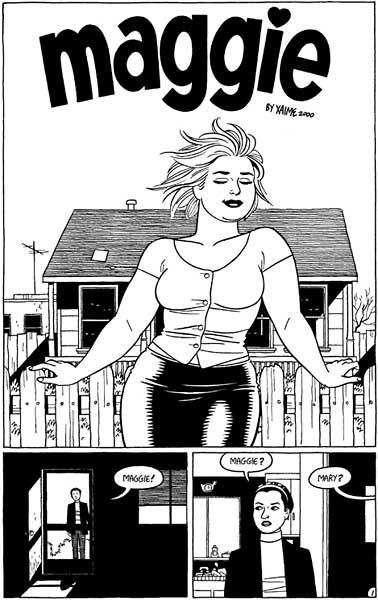

by Jaime Hernandez, 2000-2008

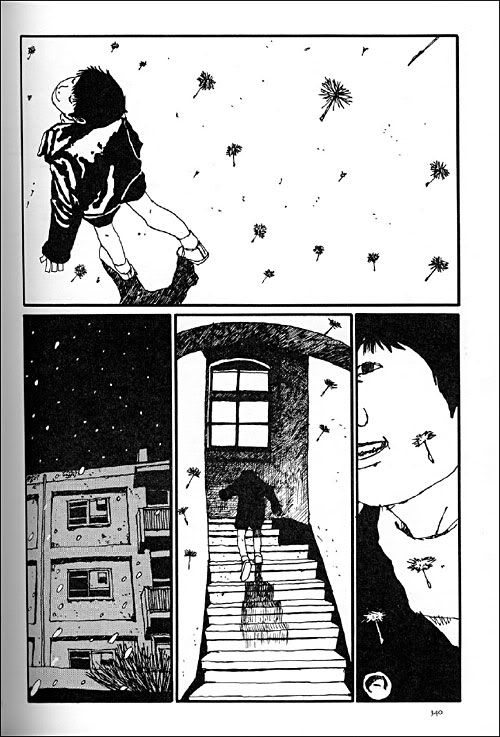

Jaime Hernandez has, since 1981, when Love and Rockets first appeared, been one of the greatest of American cartoonists, and also one of the greatest storytellers in comics. While his brother Gilbert's contributions to the series they created together spanned all over the map — from surrealist gags to bizarre fantasy stories to the South American drama of Palomar — Jaime's work was increasingly focused, with singular intensity, on the characters of his Locas saga. The story of two young Chicana punks, Maggie and Hopey, this low-key epic has now been a work in progress for nearly 30 years. Jaime has made his characters age and change with time, introducing new characters in the process and constantly shuffling around his cast, exploring the ways in which people grow and develop, the way friendships break and repair, the way loves ebb and flow as time goes by. It's an affecting punk soap opera, and the more history accumulates behind these characters, the richer and deeper Jaime's stories get.

Jaime Hernandez has, since 1981, when Love and Rockets first appeared, been one of the greatest of American cartoonists, and also one of the greatest storytellers in comics. While his brother Gilbert's contributions to the series they created together spanned all over the map — from surrealist gags to bizarre fantasy stories to the South American drama of Palomar — Jaime's work was increasingly focused, with singular intensity, on the characters of his Locas saga. The story of two young Chicana punks, Maggie and Hopey, this low-key epic has now been a work in progress for nearly 30 years. Jaime has made his characters age and change with time, introducing new characters in the process and constantly shuffling around his cast, exploring the ways in which people grow and develop, the way friendships break and repair, the way loves ebb and flow as time goes by. It's an affecting punk soap opera, and the more history accumulates behind these characters, the richer and deeper Jaime's stories get.In the 2000s, after a brief experiment in telling stories in their own separate series, Jaime and Gilbert reunited under the familiar Love and Rockets banner for a second series. Gilbert's satiric wit and outlandish style are still intact, but somehow his work in recent years seems increasingly remote from the emotion and heft of his best stories, which is why he is sadly absent from this list. Jaime, however, just keeps getting better. The Locas-related stories in volume II of Love and Rockets are some of his best work, examining his heroines on the cusp of adulthood, feeling that they now have to mature but reluctant to leave behind the wildness and fun of their youths. These are moving, graceful stories, about growing old, about making new starts, about body image and nostalgia and having a sense of home.

The peak of Jaime's recent output can especially be found in a pair of books collecting his final contributions to Love and Rockets Vol. II. Ghost of Hoppers is one of his best standalone works, focusing on Maggie as she reappraises her life following a divorce. This book is infused with elements of horror and fantasy, but its emphasis is on this 30-something's nostalgia for a home she no longer feels any connection to. As she revisits the sites of her past, scenes from her punk glory days poignantly weave together with the vision of her as an older, chubbier, tired woman. As with all of Jaime's recent work, it draws much of its power from the rich history of this character, but at the same time the polished beauty of his cartooning, and his efficient storytelling, prevent this book from being one for the hardcore fans only. The same is true of the follow-up volume The Education of Hopey Glass, which turns to the artist's other central character, a wild girl who's realizing that, without even meaning to, she's taken the first few steps towards maturity. Jaime's storytelling, his sheer drawing chops, and his obvious love for these complex characters, make these books some of the most moving works in all of comics. There is no greater all-around artist in modern comics than Jaime Hernandez, and his recent work builds on his past successes so that his oeuvre as a whole is shaping up to be one of literature's best sustained stories about aging and the shifting of relationships over the course of a life. I will gladly follow Maggie and Hopey and the rest of these people wherever Jaime chooses to take them. [buy] | [buy]