La Notte is perhaps Michelangelo Antonioni's most complete portrait of the deadened emotions that constitute his essential subject, the boredom and disconnection and lack of communication in a drastically changing modern world. In the first twenty minutes of the film, the married couple of Lidia (Jeanne Moreau) and Giovanni (Marcello Mastroianni), a novelist, don't say a word to one another as they go to visit their dying friend Tommaso (Bernhard Wicki). They turn to one another occasionally, seemingly about to speak, their lips starting to move, a rueful smile reflecting their uncertainty with one another, but they never say anything. With Tommaso, they each speak to him independently but still say nothing to one another, as though they're each dealing with their individual grief and sadness over their friend's illness. They're together and yet locked off from one another, and when Giovanni is assaulted by a young "wild woman" in an adjoining room, a sexy lunatic in a black slip who fixes him with a dark, unrestrained stare and throws herself onto him, he allows her to lead him into her room, kissing her and letting her pull him down onto her bed until the nurses discover them and restrain the girl. This moment of unhinged passion, crazy and illicit, reflects what's missing from the married couple's life, and the same point is made when Lidia and Giovanni go to a club together where a black woman, assisted by a muscular and shirtless black man, performs a striptease with contortionist maneuvers, hypnotizing Giovanni, who ignores his wife to watch this display of physicality and open eroticism.

La Notte follows this couple through the remainder of this troubled night and into the next morning. It's about their distance from one another, their distance from their own past. After their visit with Tommaso, they spend much of the film apart from each other, occasionally coming together only to split apart again, to go off on their own, each suffering and thinking in solitude. Lidia wanders the city, exploring the neighborhood where the couple had lived together earlier in their relationship, as though nostalgia could help her to recover some of that earlier happiness, or at least to understand what had gone wrong. Later, they go to a party together, where they each flirt with other people, losing one another on the sprawling grounds of the mansion where the party takes place.

The film both captures and embodies their alienation and their ennui, their feelings of aimlessness and abstracted loss. La Notte is often boring, as Giovanni and Lidia wander around the party, exchanging banalities with the other guests, meaningless chit-chat that only augments the sense of pointlessness pervading everything. That's why Antonioni has made the ultimate portrait of modern boredom, risking boredom in the process: he incorporates boredom into his film. He allows his audience to be bored right along with Giovanni as the host, the rich real estate developer Gherardini (Gitt Magrini), tries to position himself as a kind of artist, tries to pretend that he's like Giovanni, that he doesn't care about money. But the man is a bore, a self-important fraud who just likes to hear himself talk — and who tries to hire Giovanni to apply his literary talents to writing press releases and advertising copy for his business, a fairly naked example of commerce attempting to seduce and co-opt art, and art wavering on the verge of acceptance, out of indifference and insecurity.

Giovanni's disaffection as a writer mirrors the disaffection in his life: just as he feels that he no longer knows how to communicate in writing, he fails to communicate with his wife, and a gulf opens up between them, represented in the film by their isolation from one another, by the sense that for much of the film they're each engaged in their own individual stories rather than coming together for a single story as a married couple. During the early sequences of the film, Lidia wanders the city alone, pausing to watch some boys shoot off rockets in a park and to break up a violent fight between some other young men, but mostly just silently walking through a modern urban landscape. The film has a strong vertical feeling in these scenes, an upward tension in the compositions, which seem to be constantly drawing attention toward the top of the frame. Lidia is often positioned in the lower portion of the frame, with large blank walls filling the space above her. The sounds of airplanes and helicopters passing by overhead call her attention — and the audience's — towards the sky, as do the skyscrapers looming around her, stretching up towards the top of the frame seemingly without end. When she watches the boys shooting off rockets, the camera tilts up to watch one of the rockets spiraling up until it disappears, leaving behind a gray corkscrew barely differentiated from the pale, featureless gray of the sky itself.

Later, at the party, Giovanni grows enamored of the younger Valentina (Monica Vitti), while Lidia is slowly pursued by Roberto (Giorgio Negro). The boredom and isolation of the party is then broken up by scenes of sensuousness and charming flirtation, scenes that hint at a break in the endless disconnection and lack of communication plaguing all of these characters. A rainstorm is greeted, not as an end to the festivities but as an excuse for the embrace of excess and carnality, as the guests jump in the pool, writhe about in the rain, run around laughing and screaming as they're soaked. Roberto takes Lidia for a ride in his car, and Antonioni's camera follows alongside the car in a lengthy tracking shot, the rain streaming down the windows and distorting their faces into impressionistic blurs, which are alternately illuminated by streetlights or swathed in darkness so that they create silhouettes in the dark. They're talking and laughing in the car, but there's no sound of their dialogue on the soundtrack, so this moment of connection and warmth, so unlike the quiet, standoffish scenes between Lidia and Giovanni, is presented from a formal distance, allowing the pair their private intimacy.

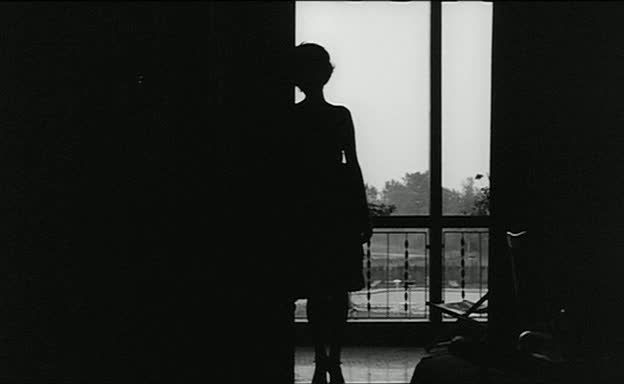

Once the titular night falls, indeed, shadows and silhouettes predominate in the film's visual vocabulary, as in the sequence where Valentina, half veiled in shadows, tells Giovanni that she doesn't want to break up his marriage, the shadows suggesting that she's only telling half the truth. Later, when Giovanni and Lidia leave the party, Valentina bids them both goodbye together, as a couple, and then stays behind, a silhouette against the window, her curved body blending into the darkness left in her room as the early morning light seeps in from outside. These poetically beautiful images add to the sensation of picturesque ennui: these deeply sensual images capture the characters' isolation and loneliness, their disconnection from each other. When Giovanni first sees Valentina, it's through reflections, a false image of the woman hovering like a ghost within a large glass pane. Giovanni's own reflection is superimposed into the window so that it almost looks like he's walking directly towards the woman, and then the camera pans right and the reflections shift, and the geography is completely reconfigured as Giovanni steps in from another angle. Such misleading images, in which perceptions shift and reflections create doubled or tripled doppelgangers, suggest that even at such junction points of potential connection, there are multiple layers separating and confusing these people, like the glass that divides them and projects them outside of themselves.

As Valentina says, in a moment of confession that could apply just as well to either Giovanni or Lidia, "whenever I try to communicate, love disappears." That's the central dilemma here, this inability to maintain connections through communication. These people, dwarfed by the clean, unadorned surfaces of urban living, shrouded in shadows, fenced in by concrete and split in two by glass, look to the past — the railway that ran through the neighborhood where Giovanni and Lidia once lived, the tracks now overgrown with weeds and decaying from disuse — but find no comfort or stability there, either. When, at the end of the film, Lidia reads Giovanni a very moving love letter he once wrote her, he doesn't even recognize the words as his own, asking her who wrote it. He can't communicate that passionately or that clearly anymore. In the final shot, the couple embraces, going through the motions, half struggling against one another and half trying to recapture that depth of feeling, as the camera pulls back and pans discretely away, leaving them increasingly small and isolated, together, lying in the sand trap of a golf course.

"La Notte is often boring, as Giovanni and Lidia wander around the party, exchanging banalities with the other guests, meaningless chit-chat that only augments the sense of pointlessness pervading everything. That's why Antonioni has made the ultimate portrait of modern boredom, risking boredom in the process: he incorporates boredom into his film."

ReplyDeleteHa Ed!!! Love it!!! Though of course this purposeful deceit has been a bone of contention with those who never cared for Antonioni (like Orson Welles). But I'm with you completely and actually regard this as the masterpiece of the Trilogy, with L'ECLIPSE within a hair. Emotional desolation has never been cinematically transcribed so numbingly, and the metaphorical camerawork by Gianni Di Venanzo is stunning. I won't ever forget the golf course, smimming pool and night club sequences especially. What you say here about alienation, aimlessness and the inability to stay together is telling and has some topical relevance from a more profound perspective.

Actually I don't find La Notte boring at all. Just a tad pat in that it's dealign with marital ennui -- a subject of rather logical extents and limits. L'Avventura never solbes the disappearance of Annd, and Eclipse never resolves the relationhip between Vitti and Delon (ie. will it continue or is it over before it starts?) Moreau and Mastroianni by contrast are far easier to comprehend, and thus infinitely less mysterious. Still it's a gorgeous movie.

ReplyDeleteActually I'd place La Notte in the middle of the trilogy; in my opinion Antonioni was at his peak around this time and getting better with each film. L'eclisse is a sublime masterpiece in the truest sense, a climax and a pinnacle. Only Red Desert really comes close in Antonioni's oeuvre. The mystery that David talks about is why the ending of L'eclisse is probably the greatest thing Antonioni ever filmed; that had quite a powerful effect on me.

ReplyDeleteIn comparison, I'm inclined to agree with David that the tension in this film is more resolved, but this is splitting hairs - it's still a great movie and its formally rigorous examination of marital boredom and isolation is remarkably crafted. As Sam says, the film is packed with unforgettable scenes, which I guess belies the boredom I was talking about. I stand by it, but of course boredom has seldom ever been this beautiful, this compelling. One feels the characters' boredom even while being thrilled by Antonioni's aesthetic approximations of that boredom.

Boredom, that's they key, but as long as the images are gorgeous and the women beautiful - you can handle it. L'Eclisse and L'Aventura have clear, astonishingly lovely Criterion transfers, but wither La Notte? Here in Region 1 all we have is that terrible Koch Lorber disc... it's one thing to be bored by beauty, another to be bored by grainy pixelated, subtitles-burned in dreckitude.

ReplyDeleteRed Desert is similar to me - seeing the new blu-ray edition on the big screen was to be astonished by a masterpiece - riveting my attention up until 4 A, seeing it a few years ago on the old DVD, dull to the point I fell asleep in the middle of the day

Erich, you're right, these films totally demand pristine DVD/HD transfers; the clarity, the beauty, is a big part of the point, and watching something like La Notte in some of the lousy forms currently available is akin to not watching it at all. Luckily Masters of Cinema, in the UK, have beaten Criterion to the punch on this particular one, and it's a great disc that really shows off the film's beautiful shadows, inky darkness, its implacable urban buildings and upper-class lawns.

ReplyDeleteDamn my Region 1-only foolishness!

ReplyDeleteThe Masters of Cinema label almost single-handedly makes it worth going region-free.

ReplyDeleteI'd second that sentiment. Between Masters of Cinema & BFI, I'm a very happy import movie geek!

ReplyDeletehttp://therainfallsdownonportlandtown.blogspot.com/

Currently, 'La Notte' is unavailable on DVD, at least that's what the clerk at Barnes and Noble tells me. You can pick up 'L'Avventura', 'L'Eclisse', 'Red Desert' and even the little seen 'Identification of a Woman', but no 'La Notte'. A shame because the film is certainly the equal of the landmark 'L'Avventura' and without 'La Notte' the trilogy has a front tooth missing. Maybe the film will re-emerge on DVD someday soon. For me 'La Notte' is never boring (something like 'Titanic', despite all the film's busyness, now that's boring), but then Antonioni never does any of the heavy lifting for the viewer, even has the gall the dispense with plot, and he fervently believes in ambiguity.

ReplyDeleteDoes it really matter what happened to Anna in 'L'Avventura'? She's a device to introduce Monica Vitti, who becomes her surrogate, an exchange that's alluded to when Vitti 'borrows' Anna's blouse and thus the replacement of Anna by Claudia commences -- even before Anna disappears.

But hell, Ed, you're a great critic, I'm not telling you anything you don't already know. I'm just happy you're an Antonioni acolyte like myself.

Mark, yes, La Notte is unfortunately unavailable on DVD in the US, though Masters of Cinema has released a great Region 2 DVD in the UK, which is how I saw it. Well worth going region-free, though I suspect Criterion may eventually get around to putting this one out in the US.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, yes, Antonioni is great, and everything you say about his use of ambiguity is very true indeed.

The ending, as is usually the case with Antonioni, is so marvelously ambiguous: how do we interpret Giovanni's letter? Is it sincere, or is it, as with his novels and his writing in general, banal and uninspired? Giovanni himself says he doesn't look for inspiration- only recollections.

ReplyDelete