The Terence Davies Trilogy is the British filmmaker Davies' triptych of short films made between 1976 and 1983. Obviously based on autobiographical experiences, all three films deal with the life of a gay man named Robert Tucker growing up in a repressive culture — the film is set in the specific culture of Britain in the 60s or 70s or 80s, but its depictions can apply anywhere that desires and feelings are suppressed and denigrated. These films are universal and timeless in that way, despite their specificity and wealth of detail. The films simply but powerfully examine sexual and emotional repression, Catholic guilt, confusion, grief, and the simmering hatred and despair incubated by a life of fear and lies in the closet.

The first film of the trilogy, Children, collects the childhood flashbacks of Robert Tucker (Phillip Mawdsley as a boy, Robin Hooper as a young man). As a child, the fey, quiet Tucker suffers tremendously. He is taunted and beaten at school, called a "fruit" by his classmates, who chase him home as soon as the ending bell rings, and sometimes catch him. He is tormented by his teachers as well; they can't seem to resist mocking his habit of answering their abuse and punishments with a subservient "yes sir" or "thank you sir." And at home, Tucker must deal with a brutish but ailing father (Nick Stringer) who's cold and angry, falling apart due to illness but still possessing enough strength to beat his wife (Valerie Lilley) and intimidate his son.

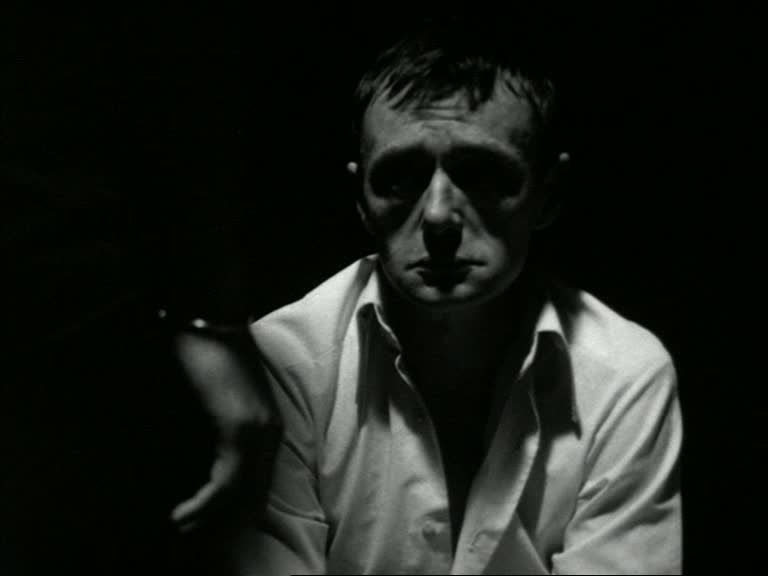

The film, like all three of these shorts, is shot in a loose black-and-white style, rough and realistic, with the deeply personal feel of lived memories. The opening, in which Davies focuses on the faces of schoolboys in silent shots, immediately recalls the Free Cinema movement, an obvious influence here, as is the style and immediacy of neorealism in general. Davies has a feel for faces, for observation. He accumulates small details until he's assembled a coherent portrait of a young gay boy's life in a repressive Catholic school: the punishment for small offenses, the bureaucracy, the near-military discipline contrasted against the brutishness of the schoolchildren whenever the teachers aren't watching. Catholic guilt and repression loom large. A cross is prominently positioned in Tucker's room so that it seems to linger in the background of several shots, juxtaposed against his suffering and anger.

The sequences of Tucker as a boy are implicitly the flashbacks of the older character, who doesn't seem much changed by the intervening years. Just as the boy goes to see a doctor in one scene, waiting in his underwear while the other boys make fun of him, the young man also goes to see a doctor. The bureaucracy of the waiting room connects the boy and the man, as does the anxiety over his homosexual desires. The boy watches, in a pool shower, as a young, muscular man washes himself: the scene is lovingly filmed by Davies as a sensuous expression of gay desire, capturing the look of awe in the young Tucker's eyes as as he watches the man's hands caressing his own body beneath the streaming water. Later, Tucker faces a doctor who seems to think of his lack of interest in girls as an illness, a temporary affliction that will eventually pass, and Tucker only politely says "thank you" and "sir" the way he always had to his teachers as a boy. A childhood of abuse and constant browbeating has turned him into an introspective, isolated young man, obviously haunted by his past. The film's structure reflects this: the scenes of Tucker as a man are brief and fragmentary, overshadowed by the scenes from his boyhood. Other than an attenuated scene of him getting together with another man, there is no sign of anything of substance in Tucker's adult life other than his negative memories of his own past.

Davies' aesthetic is unshowy, but these seemingly offhand images of prosaic life can be misleading: there's a subtle stylization in his images. In one shot, Davies shoots through the back window of a hearse as Tucker's father's coffin is loaded into it, while beyond the car's window are Tucker and his mother in another window, looking on, made ghostly by the distance and the panes of glass, as a sneering smirk curls Tucker's lips. The next shot is even more chilling, as the boy begins to laugh bitterly, and then walks forward at the head of a procession of mourners, each of whom stare disarmingly at the camera as they pass by. At the end of the shot, when all the mourners have walked by, all that's left is the black emptiness of the doorway.

The use of music and sound in the film is haunting and minimal. A static shot of Tucker and his mother riding the bus is accompanied by a mournful flute solo until, abruptly, Tucker's mother begins to sob quietly, gasping and hiccuping, her face disconcertingly maintaining its stoic composure in between sobs. In another shot, Davies holds the adult Tucker in the same static profile, staring straight ahead while a collage of sounds and music on the soundtrack evoke childhood memories: children singing and saying prayers in unison, their high voices joined together in both plaintive folk ballads and rote recitations of prayers. The most affecting music is reserved for the final shot, a long pan back from Tucker at his bedroom window, interrupted by a brief interior profile shot in which the boy breaks down and cries, moaning, "oh dad," a stark contrast to his smirking reaction before the funeral. As the camera pulls back from the window, and from this intimate moment of grief, a girl's voice sings the mournful, eerie supernatural folk song "The Ballad of Barbara Allen."

Madonna and Child, the second film of the trilogy, picks up the story of Robert Tucker (played this time by Terry O'Sullivan) later in his life, when he's living at home with his aged mother (Sheila Raynor) and working at a dull office job. Towards the beginning of the film, Davies' camera pans slowly across the deck of a ferry, tracking methodically towards Tucker, who sits alone towards the back of the boat, obviously crying. As the camera edges in closer and closer, it eventually arrives at an uncomfortably intimate closeup that reveals every messy detail of Tucker's grief: his heavy-lidded, puffy eyes, the tears streaming down his cheeks, his quivering lips. It is a powerful encapsulation of utter despair, mirrored at the end of the film by the scene where Tucker, sitting along in his room at home, abruptly screams loudly. His mother walks in, asks if everything is okay, and when he plaintively answers in the affirmative, she nods and closes the door. In both cases, Tucker's despair is seemingly unmotivated, not tied to any concrete event or incident, coming out of nowhere — but the rest of the film makes it clear that these uncontrolled emotional outbursts are an only too appropriate response to the general aura of melancholy and isolation afflicting this lonely, tormented man.

Davies' slow pan across a silent office, with the occasional scratch of a pencil or raspy cough rubbing up against the choral music of the soundtrack, emphasizes the deadening effect of this work on Tucker. This is particularly true when, in a deadpan punchline, Davies ends the tracking shot with a closeup on a wrinkled coworker, who asks Tucker if he did anything over the weekend, to which he drily responds, "no." But he does do something on the weekends, as the very next shot shows him methodically going about his sour-faced preparations for going out. He pulls on his leather boots and jeans, and his shiny leather jacket, popping the collar up around his neck. Davies emphasizes the sounds of this routine: the rustling of cloth, the metallic scrape of a zipper, the crinkling of the jacket, the creaking of the stairs as Tucker then sneaks downstairs in the dark, trying not to wake his mother. This grown man is acting like a teenager trying to get out of the house, while his mother, in a nearby room, lies awake, listening disapprovingly, knowing or suspecting where her son is going. The shot of Tucker slowly tiptoeing down the stairs, a striking black silhouette in the dark, his collar sticking up in points like Dracula's cape, emphasizes the distance between his desired image of himself and the truth of the matter, which is that he's rather pathetic, unable even to get into the underground gay clubs he tries to visit. He's so obviously uncomfortable with his sexuality that he winds up not fitting in anywhere, in the straight world or in the underground gay world he hesitantly flirts with.

The point is driven home during a remarkable scene where Tucker goes to confession. Speaking to the priest, he rattles off an impressive list of very specific sins, accompanied by precise tallies of how many times he committed each sin during the weeks since his last confession. The sins are mostly matters of thought and attitude, venial slips like "disrespecting my parents" and "coveting my neighbor's possessions." It is obvious that Tucker maintains a constant censorious eye on his own mind, tracking his impure thoughts, keeping a mental tally sheet of his bad thoughts. The unspoken subtext of this confession, however, is sexuality, the one subject that Tucker can't seem to bear to address in these admissions of failings and thought crimes. As Tucker continues to recite his sins in voiceover, Davies pans away into the black empty space of the confessional, transitioning into a fantasy or memory of Tucker lasciviously giving a blowjob to another man, the camera drifting along until it is positioned behind the man's bare buttocks as Tucker squeezes them together. Paired with the language of penitence on the soundtrack, the image is doubly provocative. It is clear that Tucker feels guilty for his sexual behavior, and his obsessive tracking and confession of his other sins becomes a form of compensation: he's struggling with feelings of guilt, and can't bear to even acknowledge his desires or his sexual actions.

The third film of Davies' trilogy, Death and Transfiguration, opens with a remarkably affecting and simply presented sequence as Robert Tucker goes to his mother's funeral. The shot sequence is precise: a hazy urban skyline with a blurry sun breaking through the clouds, the front grille of a hearse, a car door opening, a closeup of hands clasped in a prayer-like posture, the wheel of the vehicle as it slowly starts moving, and finally a closeup of Tucker's face as he sits in the back of a car, heading towards the cemetery to bury his beloved and feared mother. It is a near-abstract representation of grief, capturing the sense of ceremony and ritual that accompanies death, the ritualized gestures of mourning, the rites that precede the trip to the grave. That this sequence ends with a sustained image of a coffin being cremated, the flames flaking away the wood and slowly engulfing the screen, suggests that the ritual is merely a civilized facade on the truth, a disguise for the simpler and crueler fact that this is an absolute ending.

This final film, perhaps the most devastating of the cycle, focuses on Tucker as an old man (played here by Wilfrid Brambell, while Terry O'Sullivan returns as the middle-aged Tucker). The trilogy is structured so that each segment is about looking backwards: in Children, Tucker was a young man remembering his boyhood, in Madonna and Child he was middle-aged and thinking back on being a younger man, and here he's an old man remembering the entirety of his life. There's a sense of circularity to this structure, as the old, sickly Tucker lounges in a hospital, cared for by nuns, remembering his boyhood as a student at a Catholic school where he feared the rigid nuns who ruled his life. He has been returned to the hands of the nuns after an entire life struggling against the confines of religion, wracked with guilt over his gay lifestyle, constrained by his mother, who he devotedly cared for and desperately mourned for after her death.

Now, what's left to him is memory. Davies' fluid editing erases the boundaries between past and present, cutting smoothly between the silent, ancient Tucker in his hospital bed and various sequences from earlier in his life. He remembers, especially, moments of tenderness and intimacy with his mother, and moments of religious instruction from his boyhood. As he approaches his own death, his thoughts are obviously on God, wondering what's next for him, thinking about his fraught relationship with religion. He's also still haunted by his mother, long after her death, consumed by thoughts of her. One of the film's most beautiful sequences is a memory from Tucker's boyhood, as he remembers seeing various adults, friends of his parents, singing in the streets, exuberant and perhaps a little drunk, winding into the house for a Christmas party. Slowly, another song wells up from amidst the revelers' cacophony on the soundtrack, an out-of-tune woman's voice singing, badly but with such passion and feeling, "Someone To Watch Over Me." This song, sung boldly and clearly, with no shame over the cracked notes, slowly replaces the sounds of the party on the soundtrack, as the young Tucker sees his mother on the street and embraces her, and the song continues as Davies cuts back to the hospital, where Tucker wheezes and moans in his sleep, his mouth hanging open, his face looking gaunt and skeletal.

This film ends with a harrowing and mysterious sequence in which Tucker at long last proceeds, gasping and wheezing, into the pure white light that consumes him in his final moments. That's the moment of transfiguration hinted at by the title of this final film, but it's a singularly open-ended transfiguration, leaving one to wonder if Tucker has been lifted up into God's arms, as he had always been told he would be, or if he passed into some other void. It's a perfect, if desolate, ending to the film, and the trilogy as a whole, because it captures the isolation and loneliness of this man who was never able to be himself. He dedicated his life to his mother, and to hiding and suppressing the truth of his gay identity and desires, and in the end he's left with a lonely, frightening death, facing the light with so many questions left unanswered, so many wishes left unfulfilled.

Whe the Trilogy came out a friend asked me "Well what did you think?" I replied that it made look like Singin' in the Rain

ReplyDeleteTerence is a very great filmmaker and very complex gay man. Here's an interview I did with him when Of Time and The City came out. He's now preparing a film adaptation of Terence Rattigan's play The Deep Blue Sea. He and Rattigan are a perfect fit.

This Bronski Beat video is highly Terence-inspired.

ReplyDeleteI knew you'd be all over this one, David. It's such a great set of films, deceptively simple and yet with so much going on in terms of themes and aesthetics. The trilogy as a whole is an absolutely devastating experience.

ReplyDeleteIndeed it is. And it's all "hand made." He had next to no resouces yet produced something absolutely indelible.

ReplyDeleteHis masterful adaptation of The House of Mirth is up on You Tube, complete.

ReplyDelete"The films simply but powerfully examine sexual and emotional repression, Catholic guilt, confusion, grief, and the simmering hatred and despair incubated by a life of fear and lies in the closet."

ReplyDeleteTo say that I absolutely, possitively, unconditionally love this director wouldn't be a stretch at all. His kind of poetic cinema is beautiful and profound and imbued with theme's that inform his upbringing, his personal torment and and a long period of repression and self-imposed isolation. Davies' impressionistic strokes in painting his raw but lyrical tableux, is deam-like, yet harrowing, sometimes crossing the line into nightmare.

His two supreme masterpices, THE LONG DAY CLOSES and DISTANT VOICES STILL LIVES rank among the greatest and most emotionally wrenching films ever made, and his recent OF TIME AND THE CITY, examining his Liverpool youth and the elegiac metamorphosis of a city is extraordinary.

You have done a spectacular job bring into focus a director whom many have never been able to negotiate, yet whose wholly original cinematic language reaches the innermost recesses of the human soul.

Sam, I definitely need to explore later Davies now, starting with Distant Voices Still Lives and the other films you name. This trilogy was my introduction to the director and I was really impressed by the intensity and the awful beauty of his aesthetic. As you say, this triptych is poetic and lyrical without sacrificing the raw, even violent emotions that are obviously coming from a very deep and personal place.

ReplyDeleteThe Long Day Closes is my favorite. A sequel to Distant Vocies Still Lives it deals with the period following the death of his brutal father. And unlike the first film Terence is actually present her as a young boy. The scene where he stares out his bedroom windo and sees a half-naked construction worker across the way who smiles at him, then gaps and jumps away from the window, curling up of ht e floor in ever-so-slight panic recreates the expericne zillions of gay men have had when they found out who they were.

ReplyDeleteTHE LONG DAY CLOSES is my absolute favorite as well, as it offers up some light, as opposed it's predessesor, which is one of teh darkest of films. Some of the overhead pans in CLOSES would do Ophuls proud.

ReplyDeleteI especially love the shot of the boy waiting outside the cinema in the rain with Doris Day (Terence's absolute favorite) singig "At Sundown" on the soundtrack. That and the Love is a Many-Splendored Thing sequence where the men fall though the glass ceiling.

ReplyDeleteTerence is the British Ozu.

"Terence is the British Ozu."

ReplyDeleteAye, I couldn't agree with you more. He's supplanted Loach in that department. Love the Doris Day and SPLENDORED THING recalls too!