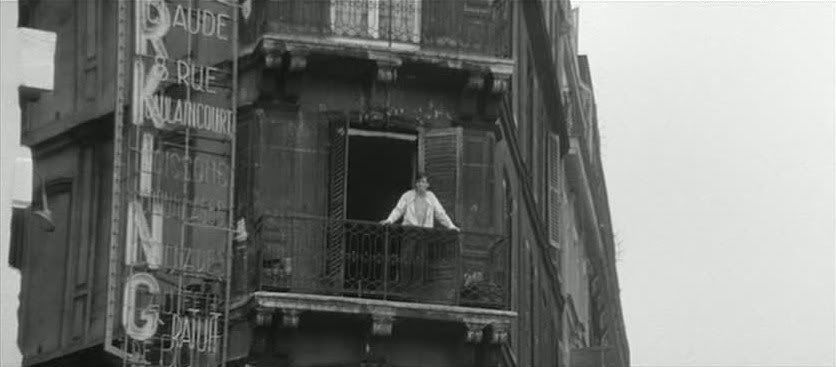

The short film Antoine and Colette, originally part of an anthology film called Love At Twenty, was François Truffaut's first sequel to his debut The 400 Blows, picking up the story of the young juvenile delinquent Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) three years after the events of that film. The film opens with a voiceover that catches the audience up on the intervening years of Antoine's life: in and out of juvenile detention, eventually landing on his feet with a job at a record company, finally getting the independent life that he'd longed for as a child. The early images of Antoine waking up alone in his own apartment and then stepping out on the balcony are the image of freedom. Truffaut's camera leaves the apartment to capture Antoine's apartment building in a long shot, zooming in on the young men as he steps out onto the balcony, overlooking the street, stretching in the morning air, a vision of freedom and independence, a young man on his own in the city.

Truffaut then further establishes the continuity between his earlier film and this one by having Antoine meet with his old friend René (Patrick Auffay), and the two friends reminisce about some of their adventures from The 400 Blows. These memories infiltrate the film in an especially cinematic way, a variation on the old iris in/out of silent film, as the frame constricts on the present-day Antoine and René to make room for their memories, in the form of a scene chopped out of the first film, which then expands to fill the whole frame. It's a very poignant moment, as the scene from the first film is nostalgic on multiple levels: for Antoine and René, remembering their childhood friendship, but also for the audience, remembering the film they'd loved so much and the playful, loose spirit that infused it, and remembering too the way these actors, now young men, had looked just a few years before, like little boys playing at being men, smoking cigars and drinking wine and gambling, then clumsily trying to hide all the evidence when a parental authority came in.

With the characters re-introduced in this essentially nostalgic way — nostalgic already for the cinema of a few years earlier, for the boyhood awkwardly blossoming into puberty and manhood — the remainder of the short concerns Antoine's unsuccessful attempts to woo Colette (Marie-France Pisier), a girl he meets at a concert. When Antoine finally gets the courage to talk to her after watching her from afar at multiple concerts, Truffaut highlights the couple, isolating them from the rest of the audience with a tight frame that only reveals Antoine and Colette, with the rest of the frame black as though everything else in the room has ceased to matter — to the besotted Antoine, at least. Reading between the lines, however, even more than this story of young love, the film is actually about Antoine's yearning for the family he'd lost, the happy family that in a sense he'd never had.

Colette rejects Antoine's advances at every turn, treating him like a friend or, more poignantly, like a brother. Indeed, Colette's parents immediately take a liking to Antoine, and at one point the voiceover says that they all but "adopted" the young man, a pointed turn of phrase considering Antoine's status as a near-orphan, with no parents who care about him. (It's touching, too, in light of Truffaut's own quasi-parental relationship with the young actor; there was more than a little of both Truffaut and Léaud in Antoine.) Antoine had been a ward of the state, and now he was on his own, and though he gets nowhere with Colette, one senses that perhaps what he really wants is not necessarily her but this family. They're so well-adjusted, so friendly, never arguing the way Antoine and René's parents had argued; there's quite a contrast between the family scenes in this film and the families of The 400 Blows.

When Antoine tells Colette's parents that he'd run away a lot as a child, they joke about it with Colette in a way that suggests they know that she'd never do that, and she seems to know that she'd never want to. They sit around the table in the family's apartment, talking and laughing, and Antoine's giggling at everything they say subtly recalls his one happy memory with his own family, a car ride from The 400 Blows when he rode in the back between his parents, watching them happy for once, flirting and joking with one another, one big happy family. This scene is an echo of the earlier one, another glimpse of a happy family for the independent Antoine.

There are other suggestions that Antoine is still yearning for the happy childhood he never had. When Colette says it must be so wonderful to be on his own, he seems ambivalent, shrugging and saying, "it depends." The conversation takes place on a dark street as the pair walk home together, and it's too dark to see the young man's face, but one senses the subtle melancholy in his voice, the sense that he's gotten what he always wanted and still isn't quite happy. This sense runs throughout the whole film, a cross-current to the emphasis on Antoine's attempts to woo Colette. The result is that, though the unrequited romance is the ostensible subject of the film, its real thematic depths reside not in the heartache of young love but in the adolescent longing for family and stability, the mingled fears and excitement of being out on one's own in the world.

Marie-France Pisier is so young and fresh here. Who knew that in a few years time she'd star in everything from The Other Side of Midnight to Celine and Julie Go Boating ?

ReplyDeleteVery true. She's a great presence already in this. I love seeing her return, older but very much recognizable, for Love On the Run.

ReplyDelete