What's a Nice Girl Like You Doing In a Place Like This? was Martin Scorsese's first short student film, and like most student films it's an indication of promise rather than a real statement in itself. The film takes a nothing premise — a writer named Harry (Zeph Michelis) becomes obsessed with a photo and finds himself unable to write any longer — and attempts to articulate the story in the most jazzed-up, stylistically vigorous way possible. The short proceeds at a rapid pace with Scorsese using successions of briskly edited still images, frequent cutaways, stop motion sequences and any other trick he can think of to illustrate Harry's rather simple story. The result doesn't amount to much more than a demonstration of Scorsese's love for the stuff of filmmaking, his fascination with editing especially. He manages to give the film a jerky, frenetic momentum that propels the film along through its innocuous, basic plot while Harry's voiceover cheerily announces each new plot development with manic intensity.

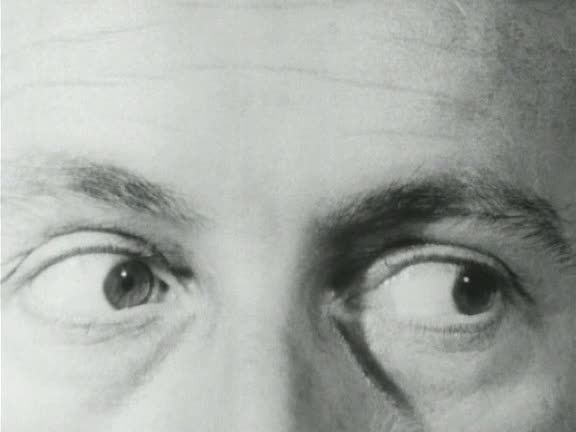

Probably the best sequence is one in which Harry watches TV late at night, surrounded by darkness, the glow from the television set casting just a small circle of pale flickering light around him. The sets are purposefully minimal, obviously, but at moments like this Scorsese makes the most of his low budget by turning austerity and simplicity into virtues. The dialogue on the soundtrack comes from King Kong, which Harry is watching on TV, and the conversation about the mysterious monster in the jungle sets the mood of dread as Harry's eyes slowly creep sideways to glance at the photo that so fascinates him. The film is much too jumpy and exuberant to be a horror movie, but Scorsese does indulge a few moments of horror movie paranoia like this, as well as in the handful of shots that focus on Harry's paranoid, widened eyes.

The short isn't exactly memorable or enjoyable beyond its relationship to Scorsese's later career, and as a comedy it's pretty unfunny, but it's an early example of Scorsese experimenting with form and using style to tell his stories.

It's Not Just You, Murray! was the second of Martin Scorsese's student films, made when he was at New York University in 1964, and it's a charming, self-consciously witty gangster picture that shows the young filmmaker already developing an interest in the milieu and the kinds of characters that would drive some of his most famous later films. Unlike his previous short, it's also lightly enjoyable for its own sake, not just as evidence of a director developing his nascent craft. The film is a mockumentary about the gangster Murray (Ira Rubin), who got his start in the Prohibition era with his good friend Joe (San de Fazio). From Murray's point of view, Joe is his greatest friend, and the two of them have built a great life together, but Scorsese repeatedly undermines Murray's narration by showing Joe betraying his partner, running away and leaving him to the cops, seducing Joe's sexy wife (Andrea Martin). It's all played for broad, winking comedy, and the playfulness of the camerawork calls constant attention to the short's meta-aware status. In the opening shots, Murray leans forward, winks at the camera, and then guides the camera to look at his expensive clothes, gesturing to each item while naming its price, then impatiently urging the camera to return to his face.

Scorsese is obviously having fun here, and if the humor is often obvious (a shot of the Lincoln Memorial zooms in to reveal "made in Japan" carved in the stonework) there's real charm in the short's fast pace and loose, jittery sensibility. The running gag of Murray's Italian mother constantly serving him spaghetti initially seems tossed-off, but the film's biggest laugh turns out to be the scene where the mother visits Murray in prison and feeds him spaghetti through the grating, squeezing the fork through with some strands of pasta hanging off. In one lightly comic sequence, Murray's nervous, stuttering voiceover rattles off all the businesses in which he and Joe had an impact, making their work sound legitimate while the images show the gangster duo collecting bribes, calling in hits, selling guns to Arabs, and leaving corpses strewn behind their path.

That's Scorsese's primary technique here, developing a disjunction between the voiceover and the images that illustrate it. It's especially satisfying to witness the contrast between the smug, self-satisfied Murray, who loves to show off his wealth and success, and the actuality of his pathetic life: his wife is clearly cheating on him and his kids look like Joe, which he comically tries to shrug off towards the end of the film, trying to twist even that indignity into a positive. It all ends with a goofy low-budget reference to Fellini's 8 1/2, but even then the hapless Murray can't be the center of attention, as Joe steals the spotlight from him even here. It's Not Just You, Murray! displays only flashes of the mature Scorsese style, as one would expect from a student film, but it does demonstrate the young director's passion for his chosen medium, his love of style. That stylistic energy would be wed to darker and more substantial subjects in later years, but the humor and verve here unmistakably remain at the root of the director's work.

The Big Shave is both the simplest and most straightforward of Martin Scorsese's early student films, and the most fully realized. It is a simple but provocative idea realized in a raw, direct way, abandoning the playful formal pyrotechnics of his previous shorts for a powerful, primal statement of anger and anguish. The film opens with briskly edited closeups of various fixtures and details in a shining white, pristinely clean bathroom: glistening, polished metal faucets, clean white linoleum, a sink with a few clear droplets of water clustered around the drain. Everything is neat, in its place, seemingly untouched. A young man (Peter Bernuth) then enters the bathroom, takes off his shirt, lathers up his face with foam and begins shaving. This is all set to the upbeat music of Bunny Berigan's 1939 jazz tune "I Can't Get Started," which lends a quaint aura to the film to match its visually pure and unstained setting.

However, the film's mood is broken as the man continues shaving even after his stubble has been clipped away. Streaks of blood begin to appear in the white foam caked on his cheeks, and soon each stroke of the razor leaves a long trail of blood on his skin, dribbling over his lips and down his neck. The effect isn't especially convincing, but it's chilling anyway, especially when at the end of the film the man slowly and deliberately draws the razor across his neck, slitting his throat while, disconcertingly, retaining a vacant, slightly bored expression, staring down the camera even as thick blood pours out of his neck and onto his chest. The last shot is, in its way, even more unsettling: a shot of the sink, stained red, as the man's hand, shaking a little, gently places the bloodied razor back on the edge of the sink, before the whole image fades to the red of the ending titles.

Those final titles provide the obvious clue to the film's meaning, as Scorsese ends the laconic title card with the direct slogan "Viet '67." It's an almost Godardian gesture, especially in the use of all that bright red fake blood, and the film is a radical political protest, a statement of anger at all the violence and wasted lives of the war. The young man in the film is just about the right age for the draft, just about the right age to be a soldier, and Scorsese's film seems to suggest that what war means for young men like this is death, pure and simple. The methodical nature of the violence in the short is an analogue for the war machine that tears apart men like this with that same casual disregard for their lives and their bodies. It's a horrifying and nastily effective short, an early precursor of the bloody end of Taxi Driver, and a bracing but indirect political statement.

Very nice Ed. Scorsese's early shorts are more experimental than his later work, though that is arguably true with most student films. Interesting, and you address this, is many of Scorsese's themes are already in place, gangsters, violence and dark humor, all of which be explored in more depth as his career progressed.

ReplyDeleteI love Murray. At times I wonder if it's not my favourite film by him.

ReplyDeleteThanks, John. I like that you can see Scorsese playing with form and style in these shorts. It's often the case that student films like this display hints of a director's future style and concerns, but rarely so blatantly as in these films.

ReplyDeleteJames, I wouldn't go that far, but Murray is definitely a lot of fun.

They're a key to Marty's entire sensibility. Goodfellas is in many ways a remake of It's Not Just You Murray. And Murray's musical "Love is Like a Gazelle" looks forward to New York New York.

ReplyDeleteThese shorts are timelessly funny.

The Big Shave is among my favorite Scorsese films. Though it's meant more as a political statement, it ultimately underlines one of his key themes as a filmmaker: a man driven to continue an action until it hurts, even kills him. Traces of that theme (if not the idea in full force) can be found in Taxi Driver, GoodFellas, Raging Bull, Gangs of New York, Bringing Out the Dead, Mean Streets, and probably more that aren't coming to mind right now. Scorsese's movies are largely about an inability to escape a social situation or even a mental state, and The Big Shave makes for an unlikely thesis for most of his filmography

ReplyDeleteGood point about those "remakes," David: these films definitely reverberate throughout Scorsese's oeuvre in some surprising ways.

ReplyDeleteJake, The Big Shave is really something, alright. It's like Scorsese's primal theme in its rawest form, without any of the niceties of character or story, just this pure statement of rage and frustration. The political content really only becomes apparent based on the time when the film was made and the ending title card. Otherwise it can just as easily be read as a general expression of exactly the kind of self-destructive (male) anguish that you're talking about.

Ed, have you seen Marty's anti-Vietnam war film Street Scenes 1970 ? I'm in it.

ReplyDeleteHaven't seen it, David, and a quick search online reveals that it's surprisingly hard to find. That's a shame, I enjoy all of his other early shorts and docs.

ReplyDeleteI saw these years ago and was intrigued but saw their value more as sociological than aesthetic (with the possible exception of The Big Shave) - it was fascinating to see Scorsese in the era that bore him so to speak. Even though his famous films are all from the 70s - 00s, at heart he's a 60s filmmaker I think.

ReplyDeleteHave you seen Oliver Stone's student films? They don't quite hold up as well. I know a guy who went to NYU around '70: Oliver Stone was in one of his classes, and Scorsese taught the class. It would be interesting to hear the teacher's comments on the student's work I think.

Joel, I wouldn't disagree that at least the first 2 student films are primarily interesting because of who Scorsese became. (The Big Shave would be fairly memorable even if it was a one-off, though.) Murray is pretty funny, but What's a Nice Girl is very slight, and both are most interesting for the ways in which they inform the director's future career. I always think these early glimpses of directors' aesthetics and interests are really fascinating.

ReplyDeleteHaven't seen Stone's shorts, though.

Great review!

ReplyDeleteWe're linking to your article for 60's Shorts Tuesday at SeminalCinemaOutfit.com

Keep up the good work!