The Traveler was one of Abbas Kiarostami's earliest features; the director himself considers it his first true feature. In a direct, pseudo-documentary style, the film chronicles the adventures of the young schoolboy Qassem (Hassan Darabi), an undisciplined kid who plots to run away to Tehran to see a big soccer match. The rough, grainy black-and-white aesthetic of the film gives it the impression of an observational documentary shot in working class neighborhoods; its schoolboy looseness and rebellious humor recall the French youth dramas of Jean Vigo and François Truffaut. Qassem is a bad kid who coasts through school, rarely paying attention in class, never doing his homework, repeatedly failing all his classes. He cares only about soccer, whether he's running around town playing pickup games with gangs of similarly rowdy kids, or splurging all his money on soccer magazines (which promptly get taken away by his teachers because he reads them in class).

His parents are ineffectual, as demonstrated in a shrilly funny scene where Qassem's mother visits the school to check up on her son and gets scolded and reprimanded by the principal for not doing enough to curb her son's lack of discipline and disinterest in school. Qassem's mother is constantly yelling at him, but he simply dodges out of the house to go play soccer; as she tells the principal, she can't read or write herself, so she's unable to help him with his work or even check that he's doing it. Kiarostami is hinting at the difficulties of developing a respect for education among working class people who are mostly uneducated. The generation gap is widened when people with no learning send their children to school, but in Qassem's case it seems that he's not likely to advance very far beyond his parents' station despite his education. If his mother is unable to do much to help, his father seems simply disinterested: his mother keeps threatening that his father will beat him for failing, but in actuality the father sits quietly, listening patiently to his wife's complaints about their son's problems, and never saying a word or doing a thing.

Class is a big part of the film. The bulk of the first half is dedicated to Qassem's attempts to scrounge up enough money for a trip to Tehran for a big soccer game. He calculates how much he'll need for a bus ticket, a ticket to the game, and some cab fare, and then starts scheming to gather the money. He outright steals a small sum from his mother, but the rest he tries to get together by selling whatever broken trinkets he can find. Kiarostami emphasizes the haggling with local shop owners, the difficulty of slowly building up a little money. In one scene, Qassem uses a broken camera — which he had earlier failed to sell — to pretend to take pictures of kids coming out of school, charging them a few cents for each photo, and planning to tell them later that the pictures didn't come out. Qassem's scheming is alternately sad and funny, and in this scene it's the latter, as the kid gets into his role, bantering with the subjects of his fake photos, calling one girl a "cutie" and joking with a mother who poses with her baby.

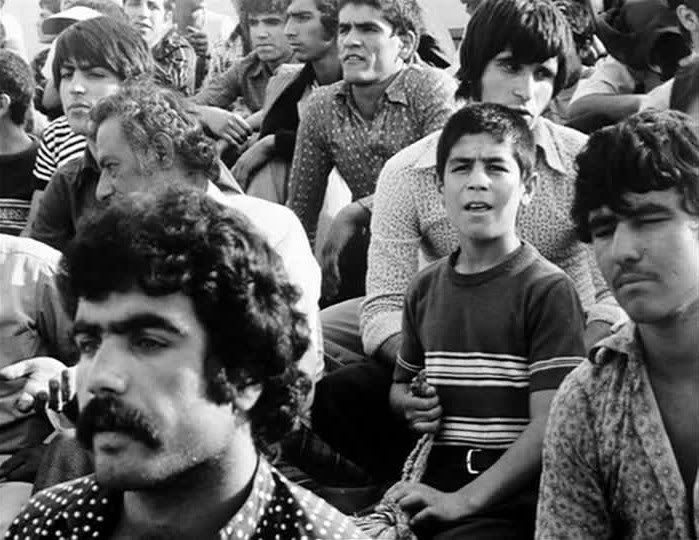

Qassem finally gets the money he needs by selling the soccer equipment that he and his friends had saved up for; he gets only a small fraction of the money they'd paid, but it's enough for his Tehran trip. In the second half of the film, Qassem finally makes his trip to Tehran, riding by night on a bus, its light cutting through the eerie darkness. Once there, however, he experiences nothing but further delays and problems in his quest to get into the game, waiting in a ticket line for hours only to just miss the cutoff before they stop selling tickets. He finally does get a ticket from a scalper, and enters the stadium through the rush of the crowds only to find that he's gotten there way too early and must wait for three boring hours before the game even starts. His conversation with an older fan suggests some of Qassem's alienation: he has few friends and sees himself as an outsider, a country boy who the city kids would never want to have anything to do with.

This note of melancholy infuses the broad irony of the film's ending. One of the film's final sequences is a dialogue-free, near-silent dream sequence in which Qassem imagines himself back in his hometown, suffering the punishments and disapproval of his parents and teachers, as well as the hatred of all his classmates, who he'd schemed against and cheated in order to make this trip. In one of the most striking sequences, Kiarostami holds a closeup of Qassem's face as he lays on the ground, screaming and thrashing around as the other students beat him and drag him along the ground. They're clustered all around him, their faces masks of anger, their eyes cold and staring. He sees his mother among those in the crowd observing his torment, her face hidden behind a wrap, only her eyes looking on, just as earlier she'd watched as a teacher beat the boy at her behest for stealing money from her. After the low-key humor and disarmingly casual aesthetic of the rest of the film, this dream sequence stands out for the way it suddenly externalizes all of Qassem's previously hidden insecurity and fear, the emotional turmoil churning within this disobedient, insolent kid.

The Traveler is a lovely, quietly moving film with some unexpected moments of sharp visual poetry. In one scene, Qassem looks through a camera's viewfinder at his friend as the other boy tries to convince him to sell the camera for a cheap price; the image in the viewfinder is cloudy and washed out, as though the other boy is far away rather than right next to his friend. Later, when Qassem finally gathers enough money for his trip, he celebrates by leaping onto the back of a horse-drawn carriage, sitting on the rear of the carriage as it speeds away, leaving his friend behind. Kiarostami draws the moment out into a poetic celebration of motion and speed, focusing on the horses' hooves, the look of pleasure on the boy's face, the shadow of the carriage's driver moving along the ground as the horses pull the vehicle onward. It's a crucial moment, and Kiarostami beautifully communicates the sense of freedom and accomplishment that Qassem feels at this point, finally liberated from his working class context, his disciplinarian school, his seemingly uncaring parents. This, and not the actual (and disappointing) trip to Tehran, is the real climax of the film, the real heart of Qassem's story. His youthful yearning for freedom, his desperation for something of his own, is vividly felt through Kiarostami's calm, stripped-down aesthetic.

"This, and not the actual (and disappointing) trip to Tehran, is the real climax of the film, the real heart of Qassem's story. His youthful yearning for freedom, his desperation for something of his own, is vividly felt through Kiarostami's calm, stripped-down aesthetic."

ReplyDeleteThis is indeed a beautiful early film by Kiarostami that is notable for its (typical) class delineation, visual poetry and humanistic underpinning. It certainly is distinguished by its cinema veriye style and observational arc. I adore this director (like so may others including yourselve) and find his earlier work signals the direction he moved into with even more power and profundity.

Lovely writing.

Thanks, Sam! I was beginning to fear that nobody else had seen this one, even though it's a much-appreciated extra on Criterion's Close-Up DVD. As you say, this film definitely points forward to the director's later work.

ReplyDelete