À double tour, Claude Chabrol's third film and his first shot in color, is a boldly stylized Hitchcockian thriller that prefigures the director's later preoccupation with tearing apart the pretensions of the bourgeois family unit through murder and melodrama. It's a lurid and bizarre film, all cocked angles and garish colors, its structure occasionally darting off for serpentine, complicated flashbacks in which events are always filtered through the skewed sensibility of the one doing the remembering. Chabrol is viciously, hilariously sending up the bourgeois family, tearing it apart from the inside, ridiculing the stiffness and ostentatious formality that disguise so many sordid truths. The wealthy Marcoux family is a hot bed of dysfunction. Father Henri (Jacques Dacqmine) is openly having an affair with Léda (Antonella Lualdi), a glamorous young Italian woman who lives immediately adjacent to the Marcouxs' rural estate. His wife Thérèse (Madeleine Robinson) knows about the affair, and the couple has an antagonistic relationship based around fierce exchanges of barbed insults, constantly trying to wound one another with words. It's no surprise that their children are damaged by this tense marriage: Richard (André Jocelyn) is a clinging mama's boy, and Elisabeth (Jeanne Valérie) lashes out by dating the most inappropriate guy she can find, the relentlessly rude townie Laszlo (Jean-Paul Belmondo).

Belmondo's riotous, crude performance as Laszlo is a highlight of the film, particularly in the early scenes. He's a sloppy and free-spirited disturber of bourgeois respectability, an unpredictable presence, tearing things apart just because he can: he unfurls Thérèse's knitting, parades around naked in front of the chaste Elisabeth, tries to convince Henri to leave the family for Léda, and in a hilarious scene, voraciously downs a tremendous breakfast, slurping down drinks first thing in the morning and talking to Thérèse through a mouth crammed with food. Laszlo is everything the Marcoux family is not, untamed and unconstrained in every way, especially sexually: he's engaged to Elisabeth, but this doesn't stop him from ogling every pretty girl he sees walk by (accompanied by swirling, playful music) and, as he gets drunker, even making appreciative noises at passing grandmothers.

The Marcouxs' maid, Julie (Bernadette Lafont), is a similarly disturbing presence, which is perhaps why Chabrol opens the film with a provocative sequence in which Julie hangs out the window of her room in nothing but her underwear, taunting the gardener and the milk man — not to mention the prudish lady of the house, not to mention the audience — with her casual sexiness. Like Laszlo, Julie represents the freedom and playfulness of the lower class, totally unfettered by manners or good taste. She bathes in the voyeurism of men, and Chabrol even has Richard leer at her curvy body through a keyhole. Julie always seems to be walking around the house with a little smirk, as though she knows something that no one else does, and she's comfortable in her own skin in a way that eludes the tradition-bound upper-class characters, who have nothing but rules and obligations and codes of behavior hemming them in.

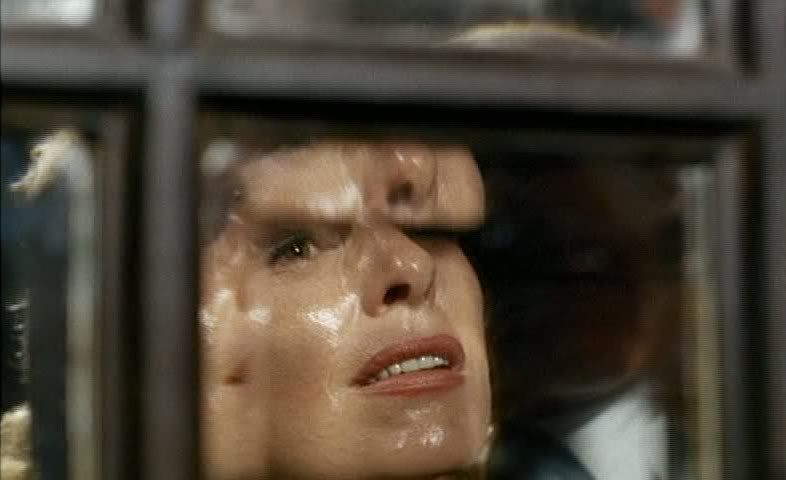

And they're anything but comfortable in their skin, particularly Thérèse, an aging woman who's continually told by her openly straying husband that she's ugly and undesirable. In one harrowing scene, he grabs her hair and holds her up to a segmented mirror, chopping her face up into jagged geometric fragments, while Chabrol playfully cuts away to a peacock strutting by on the grounds outside, a symbol of the beauty this woman feels she's lacking. Chabrol's always shooting into mirrors or through various screens, propping his camera up high for jaunty angles, shooting one pivotal scene through a greening, algae-crusted fish tank, the fish floating across the frame as a murder plays out in the background.

That's right, this is, at least sort of, a murder mystery, though it takes over half the film for the murder to occur, it's announced in the most offhanded way — by Julie, of course, who seems slightly bemused even here — and there's never really any mystery about the killer's identity. In fact, the film's structure is downright bizarre, as the murderer is identified almost as soon as the murder happens, and Chabrol then launches into a lengthy flashback in which the murder plays out, and then everything can be wrapped up. He's entirely uninterested in treating this like a conventional thriller or mystery, instead just using the murder as a focal point for all the repressed emotions and dysfunctions of this stuffy upper-class family.

The murder scene is the film's second flashback, with the first being an even longer and stranger flashback in which Henri describes his day with Léda to Thérèse. This flashback is such an idealized, romanticized vision of a Hollywood-style love affair that Chabrol seems to be mocking it, suggesting that this is simply the all-too-perfect way that the pathetic Henri imagines his affair to be. Léda, with the possible exception of a brief early scene where the milk man delivers her daily bottle, is only seen in flashbacks from the point of view of the men in her life, never in the present and never unfiltered by someone else's memory of her. She's an artificial construct, the ideal mistress, sexy and adoring and totally devoid of any personality traits beyond her vivacious manner and her slightly puzzling affection for mustachioed middle-aged men. In Henri's memory of the afternoon, the lovers' afternoon walk climaxes in a field of red flowers, where the couple smears each other's faces with awkward kisses, missing each other's mouths, while Chabrol pans up from the lovers falling into the grass to that field of red buds, bloody and foreboding.

The flashback then seems to end when the lovers part, and Léda is shown laying around in her house, dreamily mooning over Henri. But this too turns out to be part of the same intricate flashback structure, which suggests that this is how Henri imagines his mistress when he's not around her, that she simply sits around sadly thinking about his absence. He can't imagine her having any agency or existence outside of their affair.

In that sense, the film's strange, unbalanced structure — which can be offputting with its elongated detours into flashback and its purposefully blunted suspense — is just one more way in which Chabrol is undermining and satirizing this family. They feign respectability and morality, but it's a thin layer over the ugly truth: that's why Thérèse doesn't really care about her husband's blatant affair as long as there's no "scandal," but she practically cackles with spite when imagining how much suffering she'd put him through if he ever broke up the appearance of their happy home by trying to get a divorce. Richard, meanwhile, is more than a little too close with mommy, and more than a little too grabby with sis, mocking her relationship with Laszlo while groping her in a very unbrotherly fashion.

Richard's so obviously broken that it's not even remotely a shock when he is revealed as the killer, because Chabrol isn't trying to generate any mystery here, he's simply examining the ways in which bourgeois repression eventually accumulates into outrageous outbursts of violence and hysteria. The murder sequence slowly builds from the creepy, tense dialogue between Richard and Léda to the moment when Chabrol's camera does a graceful arcing turn around Richard to locate his face reflected in a mirror, which he then speaks to as his breakdown becomes more and more imminent. Notably, a fly crawls across the glass, an obvious metaphor — for feelings of insignificance and self-disgust — in a film full of obvious metaphors, and soon Chabrol captures Richard in a horribly comical closeup, briefly making a hideously distorted face for the camera before smashing the mirror. As the rest of the scene plays out, Richard's face is reflected in the now shattered glass, his eyes multiplied like an insect's in the splintered shards.

À double tour is often forgotten in discussions of Chabrol's early career, perhaps because it's so distinct from the rough, shot-on-the-streets feel of his first two features and the equally lo-fi aesthetic of his masterful fourth picture, Les bonnes femmes. This film was Chabrol's first big-budget production, a bright and stylish Hitchcock tribute that, tonally and stylistically, feels much more like the films he'd go on to make in the late 60s and 70s than the rest of his early efforts. Its status as an outlier aside, À double tour is a rich, engrossing and darkly funny film that, like much of Chabrol's best work, is downright savage in its satire.

This was the very first Chabrol I saw -- back in 1961. Fascinating for what you point out reagrding its wildly varinyg tones. Belmondo and Laffont and comic characters -- upsetting the bourgeoisie with their high spirits. But Antonella Luladi is the true source of trouble as she's too beautiful to live.

ReplyDeleteThe son's murder and the clear sense at the end that the family will gather round to protect him from prosecution is exchoed upteen years later in Girl Cut in Two -- Chabrol's penultimate film and an absolute masterpeice.

Belmondo and Lafont were the highlights for me here, both of them funny and sexy as hell in equal measures, but the whole thing is weird and really interesting.

ReplyDeleteNice connection to A Girl Cut In Two, which I wouldn't have cited as a masterpiece but is definitely another interesting film dealing with some similar themes - although it's nowhere near as funny. Loved the richly symbolic ending of that one, it pretty much made the movie for me.

That theme of the the "family gathering around to protect the criminal from prosecution" also occurs in the magnificant La Rupture as well, as the respectable family of Stéphane Audran's insane husband (who has slipped in the meantime into a catatonic state) take it upon themselves to hire a private detective to systematically destroy Audran's character before she can divorce him.

ReplyDeleteAnother great movie, Colin. Chabrol obviously uses this motif of cover-ups to satirize the bourgeois insistence on avoiding consequences and not paying for their actions. The idea of bourgeois responsibility-avoidance is also picked up by Michael Haneke, who's been on my mind lately since I've been rewatching his films.

ReplyDelete