[This post is a teaser for the third annual For the Love of Film blogathon and fundraiser, which will be running from May 13-18. This year, hosts Marilyn Ferdinand, Farran Smith Nehme and Roderick Heath have dedicated the week to Alfred Hitchcock, whose early (non-directorial) work "The White Shadow" will be the beneficiary of any money earned during the event. Be sure to donate!]

[This post is a teaser for the third annual For the Love of Film blogathon and fundraiser, which will be running from May 13-18. This year, hosts Marilyn Ferdinand, Farran Smith Nehme and Roderick Heath have dedicated the week to Alfred Hitchcock, whose early (non-directorial) work "The White Shadow" will be the beneficiary of any money earned during the event. Be sure to donate!]Although Alfred Hitchcock would come to be known primarily as the master of suspense, he would not truly earn this reputation until the second half of the 1930s. Before then, and certainly in his formative years during the silent era, Hitchcock's material often tended more towards melodrama than thrillers. His sixth completed feature, Easy Virtue, is a romantic melodrama based on a Noel Coward play, the story of the divorced woman Larita (Isabel Jeans), who travels to Europe to escape the scandal of her broken marriage. Hitchcock does what he can with this rather lame material, but it's mostly a pretty slack, intermittent (not to mention incredibly sexist) drama in which the young director is still experimenting and finding his style.

Despite its brevity, the film could not exactly be called tight, and its pacing is wildly unbalanced. It takes nearly twenty minutes to get past the introductory courtroom sequence that essentially serves as set-up for the plot that consumes the remaining hour. Thankfully, Hitchcock crams this sequence with visual experimentation, flashes of his characteristic biting humor, and technical flourishes that help to spice up the rote courtroom dramatics. He seems to have purposefully elongated this segment because it's the part of the film that gives him the most opportunity to play, to indulge some genre flourishes, including even a brief turn to violence with a gun. Even at this early point in his career, it's already clear where Hitchcock's interests lie: far more with the courtroom theatrics and the blend of humor and violence that he finds there than with the somewhat routine melodrama that comprises the bulk of the film after this prelude.

The second shot of the film (after a newspaper clipping) already indicates Hitchcock's playful sensibility, with an extreme closeup of a fuzzy white ball that's soon revealed, humorously, as the top of a judge's white wig, slowly curving up as he raises his head. Hitchcock then inserts several point-of-view shots from the judge's perspective as he looks around the courtroom, seeing everything as a blur until he holds up his monocle to bring a little circle within the frame into focus. Later in the sequence, at the climax of Larita's account of her husband's run-in with her artist friend — related through flashbacks — a policeman calmly strolls up to Larita and begins taking notes while her husband rolls around on the floor, apparently suffering from a gunshot wound, while the cop studiously ignores the man's thrashing. Hitchcock's deadpan humor is very apparent at moments like this, infusing the scene with a faint air of the surreal.

Hitchcock also enhances the drama of the courtroom scenes, as in the sequence where he fades between alternating profiles of Larita and the lawyer, each facing in different directions as he interrogates her, or the shot of a watch dissolving into a clock's pendulum to indicate the passage of time. Soon enough, though, this section is over and Hitchcock has to move on to the real meat of the film, as Larita flees her ugly, scandalous divorce and goes abroad under an assumed name. Once there, she meets the young, wealthy John (Robin Irvine), who immediately falls in love with her and asks her to marry him. John's stuffy upper class family isn't too happy with this unknown foreigner's intrusion in their sprawling mansion, and his witchy mother (Violet Farebrother) is especially suspicious. The film mostly slows to a halt at this point, and Hitchcock seems rather unengaged by the love story with its personality vacuum of a male lead.

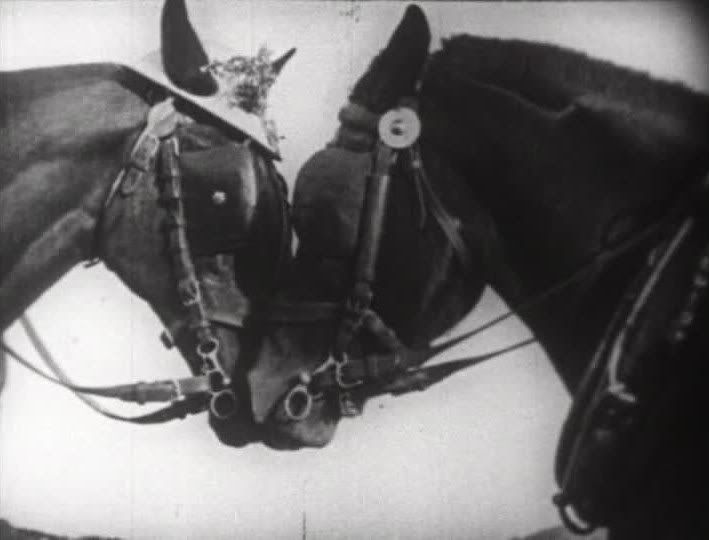

That's why he leaps at the opportunity to mock the lovers at their most romantic moment, when John proposes to Larita in the back of a horse-drawn carriage. As Larita and John kiss, the horse pulling their carriage nuzzles with a horse attached to another carriage, with Hitchcock playfully cutting from the lovers to the horses as though he finds the two images equally romantic. The scene's romance is further compromised as, behind the lovers, a car pulls up, the driver angrily honking the horn because the stopped carriages are blocking the road. This pivotal romantic moment is undercut by Hitchcock's wicked sense of humor. He follows it by showing Larita's phone call to John not directly, but through the delighted reactions of a phone operator who's listening in, a clever way of showing Larita's acceptance of the proposal.

Throughout the rest of the film, there are only periodic moments when Hitchcock's budding formal ingenuity redeems the film, as in the scene where John's mother finally discovers the truth about Larita's past. Hitchcock alternates between a bracing closeup of the woman abrasively yelling at Larita, and a somewhat aloof shot of Larita, holding herself straight as a board, her posture stiff and unflinching, her face stoic against her mother-in-law's onslaughts. Hitchcock suggests the differences in the two women's temperaments not only with their demeanor but with their respective distances from the camera.

The end of the film, after much aimless meandering and emotional flatness, finally generates some real poignancy from Larita's plight, as she sadly bows out — though not before there's an unexpected spark of lesbian subtext with Sarah (Enid Stamp-Taylor), the more class-appropriate woman who's poised to step in once Larita lets John go. At the film's finale, as the score builds up to a frenzied, bombastic climax, Larita speaks in the sublimely melodramatic final title card, "Shoot! There's nothing left to kill," as she faces the tabloid photographers eager to catch a glimpse of this notorious woman. That's an unexpectedly lurid and grandiose conclusion to a film that, with the exception of Hitchcock's occasional flashes of technical or aesthetic interest, is too often restrained and lackluster when it really demands the go-for-broke emotional intensity of that last line.

Ed, your lackluster response to this film is very much in keeping with the perceptions I've long held on, and ultimately what have kept me from checking it out. I have seen like many others in our circle nearly every single Hitchcock film with the exception of maybe three or four early titles, EASY LIVING being one. Shame too, as this was your contribution for the blogothon. But not every film can be great or even good, and Hitch for all his greatness does have a few stinkers in his filmography. A little JAMAICA INN, anyone?

ReplyDeletePoint is this is a stupendous and accurate gaging of the film!

Yeah, a lot of Hitch's early silents are nothing special; there's a few silents I haven't seen yet but otherwise I've seen almost everything he's done. All of them have at least moments, but stuff like this, Downhill, and yes, the rather lousy Jamaica Inn, are only worth seeing for those all-too-brief glimpses into the better filmmaker Hitchcock would soon become.

ReplyDeleteAnd FYI this isn't my only blogathon contribution - the blogathon hasn't even started yet, I'm just promoting it with an early post. I'll have a whole bunch to say about early Hitchcock, including a few films that are much better than this one, during the week of May 13-18.

Fair enough Ed. When I first laid eyes on this I was assuming it was an actual blogothon contribution , just posted early on. I wan't looking at it as an early promotion, but that's a great idea. I do know the vast majority of your reviews at the site are enthusiastic and positive, and that you'd certainly want to highlight that for the blogothon proper.

ReplyDeleteIn any case I am relieved, as I wan't anywhere close to completing (much less starting) my own contribution to the venture. Ha!