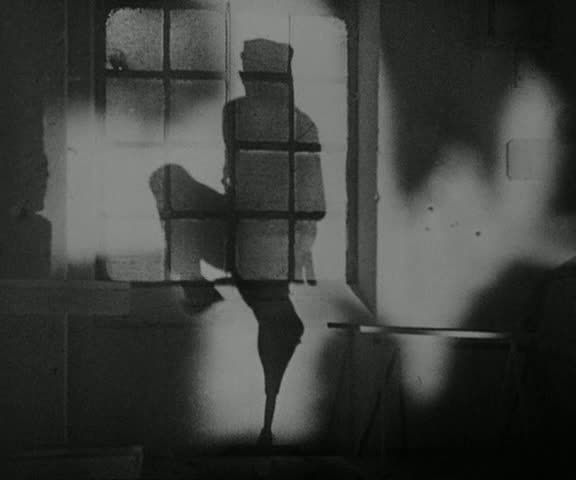

Vampyr was Carl Theodor Dreyer's first sound film, a hypnotic and dreamlike horror movie, a chilling masterpiece whose hazy, fuzzy beauty has only been enhanced by decades of wear and tear, by the degraded, scratchy quality of the surviving prints. A film that started out vague and blurry — much of it was shot with a filter in front of the camera lens to give it a distant, gauzy look — has only become more faded, more eerily unclear, over the years, its beauty and strangeness enhanced rather than hurt by its imperfections. It's a surreal and haunting experience, a rather indirect horror movie in which its atmosphere of fear arises from what's not seen rather than what's seen.

The handsome but abstracted everyman hero, Allan Grey (Julien West), is pursuing evidence of the supernatural for vaguely defined reasons, and he finds what he's been seeking in a sparsely populated small town. Grey's wanderings through the town have a feeling of surreal disconnection as he seems to be passing from the material world into a place of shadows and illusions, a world where the concrete fades into the immaterial. A farmer with a scythe rings a bell, an ominous tolling that seems to forebode grave events in the offing. Shadows are disconnected from any physical bodies, passing along walls without any sign of who might be casting the shadow. A reflection of a child runs, upside-down, along the surface of a pond, with no corresponding figure upon the shore who could be creating this reflection. A man's shadow shovels in reverse, the dirt seeming to leap from a pile on the ground to his shovel. Other shadows dance upon the walls to a sprightly tune, echoes or memories of previous eras, ghosts haunting a place where they'd once danced and played.

This imagery is creepy and somberly beautiful, and Grey is getting sucked into this strange dreamworld along with the audience. Dreyer's camera drifts and tracks behind the protagonist, following him on his wanderings, suggesting that the audience is his unseen companion on his quest. Indeed, Grey himself is mostly an observer, stumbling into the middle of a haunting horror tale that he watches play out around him like an audience member wandering in a daze through the middle of a supernatural play. Grey follows the shadows to a country estate where an old man (Maurice Schutz) and his daughters (Rena Mandel and Sybille Schmitz) are plagued by the vampire's curse. The old man is killed by a shadow soon after Grey's arrival, and then one of the daughters is attacked as well, infected with the vampire's bloodlust, grinning madly at her sister with a thirst for blood.

While all this is going on, Grey observes with mild detachment, and after each incident he returns to reading a book about vampires given to him by the old man, reading passages that both explain the action and foreshadow future developments. Interestingly, although this was a sound movie, it still feels like a silent film most of the time, and the extensive use of text contributes to that impression. There are poetic intertitles that punctuate the film early on, describing Grey's journey and mental state, eliminating the need for any expository dialogue whatsoever. As a result, Dreyer can reduce the spoken dialogue to a bare minimum, allowing most scenes to play out wordlessly, accompanied only by the expressive orchestral score. At times, even the score drops out or is reduced to a minimal murmur, exposing the hollowed-out silence of this village that seems to be populated almost entirely by shadows and ghosts. When there is sound, it's often strange and disconnected, due to the movie's post-dubbed soundtrack: people wander through the fog, their calls for their missing loved ones muted and echoey, and occasionally the silence is pierced by the clatter of horse's hooves or the somber chiming of church bells.

Dreyer also uses the vampire book similarly to silent movie title cards, interspersing excerpts from the book throughout the scenes at the mansion. The way in which Grey keeps returning to the book, as though he's more drawn to its text than to the very strange happenings all around him, contributes to the film's eerily affectless tone. Even the protagonist seems disconnected from what's going on, easily distracted by this text, immersed in reading rather than truly interacting with the sinister goings-on. Soon after, Grey becomes disembodied, his self splitting apart as his non-corporeal form has an out-of-body experience, wandering into the lair of the vampire's creepy associates, and the film's dreamlike atmosphere is especially pronounced here. Dreyer again toys with the audience's point-of-view, this time by shooting from the perspective of a body laying in a coffin, staring up at the sky and the looming buildings of the town as this coffin is carried away.

Vampyr is an unforgettably haunting experience, unsettling more for its shadowy, foggy atmosphere than for anything that happens in its minimalist narrative. Dreyer makes the vampire legend an abstracted nightmare, a journey into a strange, unstable world of shades and spirits that might just be the mind itself.

Without question one of the strangest films ever made. Reflexively catagorized as a horror film Dreyer slides along the surfaces of the genre with ever really "delivering the goods" as Murnau and Whale do. In narrative terms it's strikingly incoherent. Dreyer claimed he didn't remember making the film at all -- a neat alibi for continuity errors. Others have said he was distracted by his DP, Rudolph Mate who he had fallen madly in love with. Whether or not this was reciprocated is not known, but Mate does as lovely a job here as he was to later in the almost as incoherent Gilda.

ReplyDelete"Julian West" is Nicolas de Ginzburg, the fashion editor. And in many ways Vampyr is like a fashion spread.

There's a marvelous hommage to it in Adolphas Mekas' Hallelujah the Hills

I second the motion with the esteemed David Ehrenstein in concurring that it's one of the strangest (as you say "eeriest") of films. Your descriptive prose hauntingly captures the essence of what is probably the most celebrated surrealist work in film history, (I know CABINET is another for sure) with the famed burial seen through the eyes of a corpse, a sequence that would surely set the stage for Ingmar Bergman decades later. This is as sinister a film as the cinema has ever produced, and it was filmed away from the studio and devoid of professionals. It's definitely a film class kind of work, but it's one that invites repeated viewing with all kinds of new discoveries. Dreyer advocates that "We have changed, not the objects which are as we conceive them."

ReplyDeleteAnother great piece. You rightly stress the atmospherics over the minimalist narrative.

I absolutely adore this film, simply because it is so incoherent. It adds a level of sublime mystery that I find mesmerizing and strangely satisfying.

ReplyDeleteDavid: I know Dreyer was married and deeply dependent on his wife (at least in an interview with Preben Lerdorff Rye on the Criterion edition of Day of Wrath). Is it a prevalent theory that he was closeted?

I have no idea how prevalent it is.

ReplyDeleteAgh, I didn't mean "prevalent," I meant "popular." I suppose your answer applies there also. I've just never heard that theory about Dreyer.

ReplyDeleteIt's not a theory, it's just an anecdote.

ReplyDeleteI've heard claims of Dreyer "experimenting" with homosexuality in the 1930s, but not that specific anecdote.

ReplyDeleteMy first encounter with the film was on TV a bit over 20 years ago, in a print with Raymond Rohauer's name stamped on it. It was about ten minutes shorter than the full-length film, at least one scene was in the wrong place, and parts of the film were in English (and one part in French). And the English-dubbed bits were still subtitled in English with the rest of the film. Somehow this mess of a print only added to the overall feeling of the film; as splendid as the restored version on DVD is, that mangled text I first watched in 1991 still holds an odd place in my heart.

Vampyr was amde in several versions. What you saw was a mash-up of all of them. For once incoherence actually coheres.

ReplyDelete