Erich von Stroheim's Greed is one of the cinema's most legendary lost films, another in a long line of compromised, butchered, hacked-up could-be-masterpieces from the unlucky director, whose complete vision rarely emerged intact from the studio assembly line. Greed suffered perhaps more than any of his other works: originally nine hours long, it was sliced apart multiple times by studio-hired editors who finally produced a two-hour release version, at which point the remaining seven hours of celluloid were recycled and discarded. Von Stroheim said of the editor who put together the final cut, "the only thing he had on his mind was his hat." It's hard to know what other outcome von Stroheim expected, and it's hard to know why the studios let him film these unwieldy epics in the first place when they knew they'd never screen anything even vaguely resembling the full cuts. Von Stroheim's massive projects were destined to fail, destined to be destroyed and compromised, resulting in a career strewn with wrecked partial films. He was too ambitious, and too unconcerned with commercial and practical considerations, for the era in which he lived and worked.

Greed is especially compromised; whereas von Stroheim's earlier Foolish Wives feels nearly like a complete work despite the similarly massive edits to the director's original vision, the incompleteness of Greed is very apparent. This is true of both the two-hour theatrical cut and the four-hour "reconstruction" that attempts to approximate some of the original film's narrative through the use of still images and text taken from Frank Norris' novel McTeague, the source that von Stroheim was scrupulously adapting here. Greed's fragmentary nature is obvious in either form, at times verging into incoherence, and whole characters were almost entirely chopped out of the shorter two-hour cut, so there are characters and subplots that only appear in the still frames that attempt to bridge the gap between von Stroheim's original vision and the ragged remains left behind by the studio intervention.

Neither existing version of the film is especially satisfying, though the broad outlines of von Stroheim's vision can still be discerned. This is an almost unrelentingly bleak film, and even the prospect of enduring nine hours of this misery, to end up in the film's harrowing Death Valley climax, is exhausting and disheartening. As the title implies, this is a study of avarice, of people corrupted by the love of money above all else. At the center of the film is the dentist McTeague (Gibson Gowland), a brutish lout with a quick temper and a slow intellect, who falls in love with Trina (Zazu Pitts), the cousin and girlfriend of McTeague's best friend Marcus (Jean Hersholt). Marcus, learning of McTeague's desire for Trina, graciously steps aside, until Trina wins five thousand dollars in a lottery shortly before getting married to McTeague. Marcus, who could have tolerated his friend taking his girl, now grows jealous of the couple's newfound riches.

This is a pretty miserable excuse for a love triangle. Indeed, McTeague and Trina's romance is curiously ambivalent and inconsistent, and one senses it's not entirely because of all the missing footage: sometimes this ill-matched couple seems drawn together, and sometimes they barely seem interested in one another. McTeague's marriage proposal is offhanded, as though they might as well get married just because they can tolerate each other, while Trina, with her drawn face and wide eyes, looks perpetually frightened of this bulky lug of a man. McTeague is capable of both great violence and surprising tenderness — he's introduced kissing a wounded bird and then throwing a man off a cliff for mocking his affection for the bird — but the moments of actual sweetness and love between the couple are rare. Even the moment where McTeague first grows obsessed with her is tinged with creepiness: she's his dental patient, drugged and passed out, and he leans in to smell her hair and kiss her before operating on her teeth. Once they're married, Trina grows more and more caricatured as a miserly witch who caresses her hordes of gold while denying McTeague even a nickel for a bus fare.

Everything is drawn broadly here, with bold, over-sized performances that project the intense, unrelentingly ugly emotions at the core of this story. Among the plots trimmed from the theatrical cut is the side story of the junk dealer Zerkow (Cesare Gravina) and Maria (Dale Fuller), who he marries only because of her (possibly imagined) stories about a treasure trove of gold plates she once possessed in her childhood. This subplot echoes the increasingly unhappy romance of the leads, and foreshadows the grisly end of their tale. Zerkow is a rather nasty and obvious anti-Semitic caricature, a grasping, greedy Jew who's only obsessed with gold, but he barely stands out here because nearly everyone in the film has the same traits, the same lust for gold (inevitably tinted yellow whenever it appears), the same singleminded fixation on riches to the exclusion of all else.

Von Stroheim is crafting a mocking satire of middle class desires, which is especially apparent during the lengthy wedding sequence. While Trina and McTeague are getting married, a funeral procession passes below, the black-clothed mourners passing by on the street, visible as a long parade through the window behind the preacher who's officiating the wedding. After this gloomy association of marriage with death, the wedding becomes a series of materialist rituals: the bride and groom greedily open the gifts, and then everyone stuffs their faces in an orgy of gluttony. After the wedding is over, as the guests are leaving, Trina becomes overcome with fear: she's terrified of the wedding night physicality to come, the encroaching loss of her virginity. She looks at her new husband with eyes wide, covering her mouth as though shivering before a monster, and then she sees him replaced by an image of a bird cage with two birds trapped inside. That's the life she sees before them, a mutual prison with no hope of escape.

Clearly, von Stroheim isn't especially interested in subtlety, and Greed is an interesting, unresolved blend of theatrical overstatement and quotidian realism. Von Stroheim was apparently committed to capturing the full sprawl of Norris' novel with all its detailed depictions of poverty and daily money woes for the lower middle-class, living check to check and juggling bills to survive. Traces of this sensibility survive in the extant versions of the film, always balanced against the more melodramatic, grotesque exaggerations of the performances and the over-the-top characterization of nearly everyone as being cartoonishly overcome with lust for gold. In the most literal depiction of that lust, slightly trimmed and censored for the theatrical release, Trina actually strips naked in order to crawl into a bed strewn with gold pieces, so that she can feel the gold against her bare skin.

Von Stroheim's aesthetic naturally tends towards the grandiose in this way; he unfailingly thinks big, which is perhaps why he kept trying to make nine-hour movies and why he filled those enormous canvases with bold, expressive symbolic images. When Marcus is in the middle of a seemingly jovial, friendly conversation in which he tells Trina and McTeague that he's going away, von Stroheim cuts away and inserts an interlude of a cat squinting hungrily up at McTeague's caged birds. The symbolism is obvious, and undercuts the seeming sincerity of Marcus' promise that "bygones is bygones." In the subsequent scene in which McTeague receives a letter ordering him to stop practicing dentistry without a license, a cat stalks around the frame in the background, still eying that bird cage, connecting this incident back to Marcus, who apparently provided the information about McTeague's illegal business.

Von Stroheim, channeling Norris, is creating a sustained, narrowly focused study of the grim fate awaiting all of these money-obsessed people. The only small bright spot of decency in the film, ironically all but chopped out of the theatrical cut, is the sweet, shy romance of two good-natured elderly neighbors whose pure, kind love provides a contrast against the selfishness and nastiness that corrupts and destroys the other relationships in the film. Although the film is horribly mangled at only two hours, and not much better in its awkwardly reconstructed form, it's also hard to imagine it at nine hours, which would have to seem overwhelmingly excessive for such a singleminded study of a simple theme.

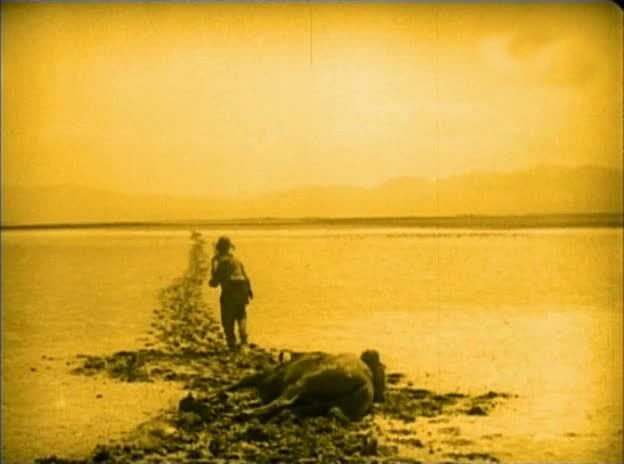

In any event, Greed is a flawed, fascinating, incomplete epic, from its bleak opening portrait of McTeague's youth with a drunken, philandering father and unhappy mother, to its harrowing, sun-drenched Death Valley climax, which von Stroheim, to the chagrin of his crew, insisted on shooting in the actual sweltering Death Valley heat. As with many of the director's excesses, it's hard to say what effect this verisimilitude had, but the sequence is undeniably powerful, with its minimalist desert vistas coated with a pale yellow filter to evoke the heat pouring down from the sun overhead. Whatever Greed might have been if its full version had remained intact, it has survived as a mere scintillating fragment of what must have been a great and possibly insane landmark of the cinema.

Even in its ruined form Greeed is a fascinating piece of work. But because of the legend of the 7-8 hour cut the film we always "see" is the one that isn't there.

ReplyDeleteStroheim was attempting to put an entire novel on film (though with cosiderable alteratiosn as Jonathan Rosenbaum's invaluable BFI book on the film shows) What he was trying to do was fully achieves by Rainer Werner Fassbinder in his adaptation of Alfred Doblin's Berlin Alexanderplatz -- whose character have much in common with Stroheim's.

rare watch !!

ReplyDelete