Claude Chabrol's Merci pour le chocolat cleverly wreaks havoc with the underpinnings of the bourgeois family, disrupting its stability at every turn, eating away at its foundations until the family seems to be propped up only by lies, jealousy, suspicion and violence. The film opens with a wedding, as the chocolate heiress Marie-Clarie (Isabelle Huppert) and the virtuoso pianist André (Jacques Dutronc) get married — though they've actually been married before, and are now getting remarried after the death of André's second wife. During the ceremony, Marie-Claire even quips that they're using the same rings as they had the first time around. The gossipy chatter of the guests — with Chabrol's camera, predatory as ever, endlessly circling around them — only further undercuts this institution, this ceremony, that is ordinarily seen as the bedrock of bourgeois respectability. The rest of the film will further disrupt family structures, calling into question the foundations of paternity and inheritance: in this film, parentage is always vague and uncertain, shrouded in multiple deceits.

The plot is built around a long-ago confusion regarding André's child with his second wife, Lisbeth: there had been a momentary switch when André had been shown a baby girl as his own, rather than the son who was, apparently, actually his. Now the girl, Jeanne (Anna Mouglalis), is grown up and coincidentally also training as a pianist, and when she finally hears the story, she decides to visit André. As she ingratiates herself into André's home and begins taking piano lessons from him, she gets tangled up in a strange chamber mystery as she witnesses the odd behavior of Marie-Claire, who's outwardly solicitous and pleasant but seems to be masking a deeper chilliness and some odd behavior involving the hot chocolate she makes every day. Multiple suspicions arise, mostly revolving around the death of André's second wife, who'd died in a car crash, her system full of alcohol and sleeping pills.

It's obvious, of course, what happened, though Chabrol is typically indirect. Even when Marie-Claire thinks back to the night Lisbeth (Lydia Andrei) died — the flashback is triggered by Marie-Claire's expressionless face dissolving into a scene of the family clustered around André's piano — there's no decisive indication of foul play. Instead, Chabrol's camera subtly insinuates by showing Lisbeth by the piano, walking away to go out, passing Marie-Claire, who watches the car pull away out the window and then walks over to the piano, the camera drifting over with her to watch her take the place previously occupied by André's wife.

It's that stalking, insistent camera that makes all of Chabrol's thrillers so distinctive. The camera circles around the characters, probing their relationships with its ever-so-slow turns, its persistent and incremental process of tracking around them, getting closer and closer without quite ever penetrating the surface. At one point, Marie-Claire enters a room in which Lisbeth's photographs are displayed. The camera lags behind her as she walks past it into the room, staring at a point offscreen, and then the camera tracks through the empty space, finding her face again in the blurry blankness, and continues past her to reveal the photo she's staring at, a head-on self-portrait of Lisbeth resting her face in her hands. Downstairs, Chabrol's camera begins circling again, as André and Jeanne listen to a piano recording together, Jeanne resting her face in her hands exactly as Lisbeth had — the girl has seen the photo, and is obviously evoking the dead woman's pose, which suggests that in a way Jeanne is as calculating, as manipulative, as Marie-Claire herself.

But they both hide it so well. Huppert and Mouglalis deliver subtle, subdued performances, each of them presenting a lovely, friendly exterior that perhaps masks something more calculating: in Marie-Claire's case, a truly sociopathic indifference that reveals itself, chillingly, in the final scenes, and in Jeanne's case a perhaps more benign penchant for selfish scheming. After all, as soon as she hears of the mix-up with André, knowing that he's a famous pianist, she seizes the opportunity to sneak into his life, to earn his help. Chabrol, by linking these women, seems to be suggesting that the sinister evil of Marie-Claire is only the most blatant manifestation of this kind of bourgeois self-interest. At root, it's about an insistence that surfaces are all that's important: "keeping up appearances is all that counts," Marie-Claire tells the board of the chocolate company she's inherited. She's talking about chocolate packaging, but she could just as well be talking about a broader bourgeois philosophy of life, a deep-seated belief that appearance is all that matters, even if the truth has little relation to the appearance.

That ties back into all the confusion over parentage: even beyond the baby mix-up, Jeanne eventually learns that she was conceived through a sperm donation from an anonymous man, while Marie-Claire reveals that she was adopted, which means that the chocolate fortune she's inherited is not her biological right after all. Considering how important biology generally is in the ancient roots of inheritance, these biological disconnects muddy the waters, slyly chipping away at the ways in which wealth and prestige are passed down through bourgeois families. Marie-Claire, especially, is an infiltrator, an adoptee who's taken on a bourgeois mantle but is essentially in disguise, a pretender. At the end of the film, she has a startling scene — remarkably honest and direct after all this shiftiness — in which she confesses that the happy homemaker guise she presents to the world is just that, a mask, a façade. "I have a knack for doing wrong," she says mildly, her face blank, when she's finally been caught in her deceits and schemes. "Instead of loving, I say 'I love you,' and people believe me."

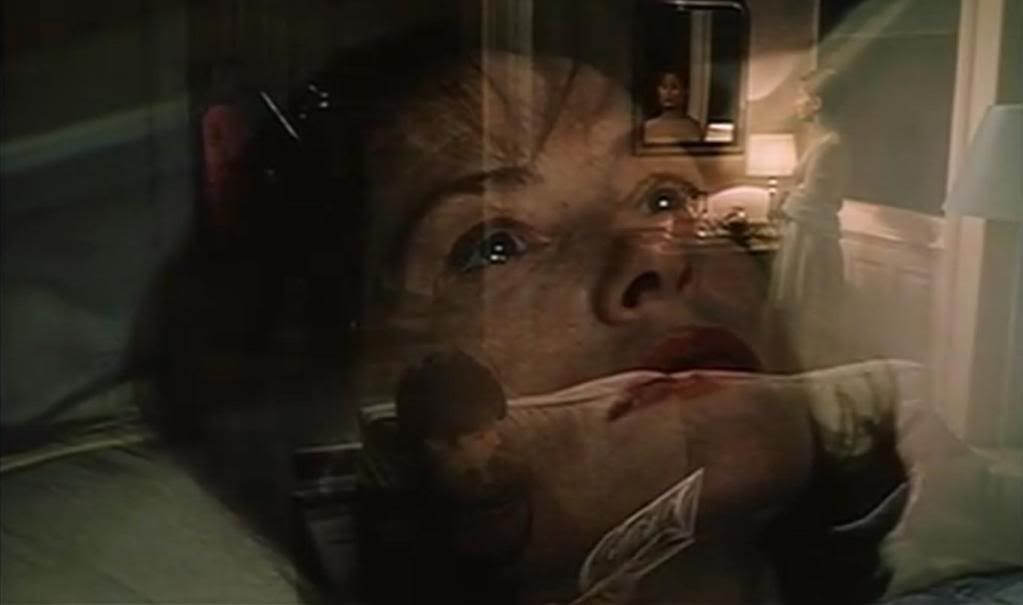

This is a sharp, smart, low-key thriller that revolves around all these mostly unstated tensions about family. It has a typically chilly Chabrolian tone that is periodically broken by bursts of genuine emotion, like the lengthy final shot of a wet-eyed Marie-Claire, or the scene in which André's son Guillaume (Rodolphe Pauly) remembers his mother's death in a sloppy outburst of raw feeling. As usual for Chabrol, the biggest secret here is not anything to do with the plot, but rather a bigger secret, maybe even the biggest secret, which is the essential flimsiness and silliness of bourgeois conventions, which can hide so much.

No comments:

Post a Comment