Eros

Eros is an anthology film that brings together shorts from three international directors — Hong Kong's Wong Kar Wai, American director Steven Soderbergh, and Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni — for an old-school throwback to the heyday of the portmanteau film. The subject, naturally, is eroticism, and all three directors come at it from very different directions.

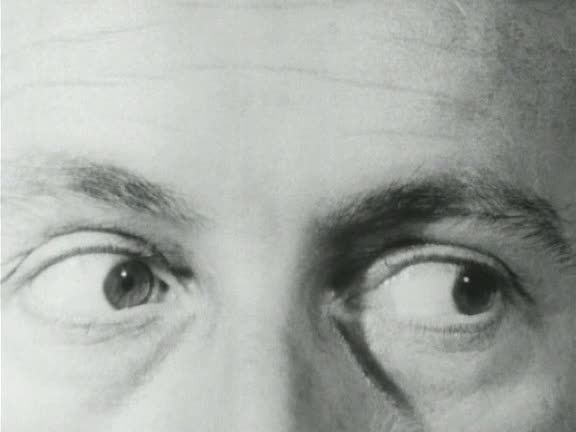

The Hand is Wong Kar Wai's contribution to the anthology, and its eroticism is inflected with a deep, poignant sadness, a sense of regret and loss that's built into the film's very structure. The opening shot is a sustained closeup of a man having a conversation with a woman who remains offscreen throughout these introductory minutes. The woman is obviously very ill, close to death, and the fact of her imminent death seems to be encoded into their conversation, into the way they talk about the future without really seeming to believe that there's any future for her. Their words eventually trigger a reminiscence about their first meeting, and Wong transitions smoothly into the extended flashback that will eventually bring the film back, full circle, to this moment, to continue this sad goodbye. Even within the flashback, the woman remains tantalizingly offscreen for some time, as the man, younger then, goes to visit her for the first time. He is a tailor's apprentice, Zhang (Chen Chang), and she is the high-class call girl Ms. Hua (Li Gong) who, due to her many wealthy clients and suitors, is rich enough to afford the most expensive, lavish clothes, so she's attended to by the tailor like nobility.

Wong deliberately withholds the image of the woman, retaining the air of abstraction achieved by the opening's closeup on the man alone. When Zhang goes to see his client, he first has to wait in the next room while she services a lover, and the sounds of their noisy lovemaking drift through the wall as Wong shoots the back of Zhang's head and the wall behind which the woman is moaning and crying out. Then, Zhang is called in, and still the woman is hidden from view by a wall, as she interrogates the nervous, shy young man. When Wong finally cuts to an image of the woman, it's a strikingly framed shot, looking slightly down on her, with Zhang standing nearby so that his hips are around the level of her head. With her head slightly cocked back, she regards him with a sultry, hungry expression, the look of a woman with a great deal of experience and confidence. In the strikingly erotic sequence that follows, she gives Zhang his first sexual experience with her hand, eying him all the while with that steely but sexually suggestive gaze, her dark red lips slightly parted, her glamorous aura a stark contrast to the tawdry gropings of the act itself.

This one act is sufficient to provoke an erotic fascination between Zhang and Ms. Hua, one that continues to affect Zhang even as, in periodic visits to provide clothes and take measurements, he watches her age, squander opportunities for security with several of her benefactors, and eventually pass her peak and gradually begin to fade away. She grows ill, eventually, but even before that she's lost her glamor, as she pushes away the rich men who could help her, and her haughty, provocative demeanor grows tinged with sadness and regret. Soon enough, the only man for whom she really holds any fascination is her lowly and adoring tailor, to whom she gave the most casual introduction into sexuality, and who has remained an unmarried loner, sustained only by his obvious desire for a woman he has to know he'll never really have.

Eventually, the film winds back around to its opening moment: Zhang sitting by Ms. Hua's bedside in the rundown hospital room where she's wasting away. The tailor brings her a fancy new dress, intended to impress a rich American man who she hopes will be her "last chance," but that chance is of course already long gone. Instead, there's simply a startling last union between the prostitute and the tailor, replaying the first scene — this time alternating closeups so that Ms. Hua's un-made-up face is revealed for the first time, her glamor (but not her beauty) entirely eaten up by her illness — and then continuing it. This final love scene transcends its potentially tawdry details to become something bracing, and intense, infused with the kind of sadness that only comes from a wasted life, and the knowledge of just how much has been wasted.

Only Wong could make this last, defiantly un-intimate sexual contact between Ms. Hua and her longtime admirer not only erotic, but depressing and loaded with the horrible emotions that linger between them: Zhang's unfulfilled longings, Ms. Hua's regret over lost possibilities, the mutual despair over their limited lives. There's a sense that both of these people, in very different ways, are confined and restricted by class and gender roles that create only a particular set of possibilities for them, and once those possibilities are exhausted there's just nothing left for them.

Steven Soderbergh's contribution to the anthology is

Equilibrium, a clever skit based around an erotic dream and the analysis of it; it's a formal game about style and structure, light and funny, buoyed by a pair of charismatic and expressive performances. Nick (Robert Downey Jr.) is an advertising executive troubled by a mysterious dream he's been having, night after night, and to decipher the meaning of this dream he goes to see the psychiatrist Dr. Pearl (Alan Arkin). The dream itself, wordless and sensuous, forms the opening minutes of the film: the first shot is a hazy closeup of a woman's face, a little

Mona Lisa smile curling the corners of her lips. Soderbergh follows this image with a series of crisp, clean images of the woman walking, in the nude, around a strikingly designed apartment, decorated all in bright blue shades, the woman's often shadowed, silhouetted form contrasting against the diffuse lighting of the rooms. Soderbergh's images are appropriately sensual and dreamy, the camera dizzily wavering to evoke the lack of the title quality — a loss of equilibrium that the dream represents — as the woman shifts in and out of focus. The camera is never quite able to capture all of her: as she prepares for a bath, she is sometimes a hazy out-of-focus blur, sometimes a dark and curvy silhouette, sometimes clearly in view and yet partially obscured by the angles of walls or doors. The swaying, dizzy camerawork has a voyeuristic quality, and yet the images are unmistakably intimate as well, as though conveying the sense of spying on someone who's so close that there would seem to be no possibility of, or need for, hiding. It's a lovely, moody — and, yes, erotic — opening sequence.

The film then transitions into an equally stylized black-and-white aesthetic — the shadowy, strikingly lit chiaroscuro of the film noir, with slatted shadows falling lightly over everything — as Nick visits Dr. Pearl and describes this dream. At this point, the film becomes a low-key but goofy farce, as Dr. Pearl manipulates Nick into lying down on a nearby couch and closing his eyes, ostensibly to comfort the patient and facilitate their work, but really for a mysterious ulterior motive of his own. For as soon as Nick lays down and closes his eyes, the doctor carefully pulls out a miniature pair of binoculars and, while maintaining a conversation with Nick as the latter relives his dream, spying on an unseen sight through the window facing outside. Soderbergh stages the sequence as antic comedy, with Arkin broadly enacting his obviously ritualized set of gestures, which feel like familiar games that he plays, perhaps, during all of his therapy sessions. As Nick walks through the dream, Dr. Pearl pulls out a bigger pair of binoculars, rearranges his furniture to get a better angle on whatever he's looking at, and finally throws a paper airplane out the window and begins excitedly waving and making complicated pantomime gestures to whoever is across the street.

Soderbergh stages the best moments in deadpan deep-focus shots that capture Nick on the couch in the foreground, utterly oblivious to all the fetishistic antics happening behind him as he spills the details of this dream that has obviously affected him very deeply. The effect is of two different forms of eroticism competing against one another, the verbal sensual description of the dream and the pantomime play of the voyeuristic doctor. It's funny and charming because the actors are funny and charming — and because there's something inherently funny in the passing thought that Downey's verbal recounting of a sexual/sensual dream is perhaps a little nod to Bibi Andersson's famously steamy storytelling in Bergman's

Persona.

The film's finale eventually provides a further level in a wry punchline that recontextualizes all these sensual shenanigans as semi-conscious expressions of anxiety, while calling into question exactly which part(s) of the film were dreams — maybe all of them. More than anything the film seems like an exercise in style, a chance to set hazy digital color (evoking Hollywood Technicolor extravagance and the visual language of vintage advertising by way of modern technology) off against the deep blacks of noir's shadows. As a stylish and diverting little short, Soderbergh's contribution is entertaining and easily forgotten, nowhere near the emotional depths and complexity of Wong's

The Hand, but then, hardly trying to enter that territory, either.

The final segment of this anthology is Michelangelo Antonioni's

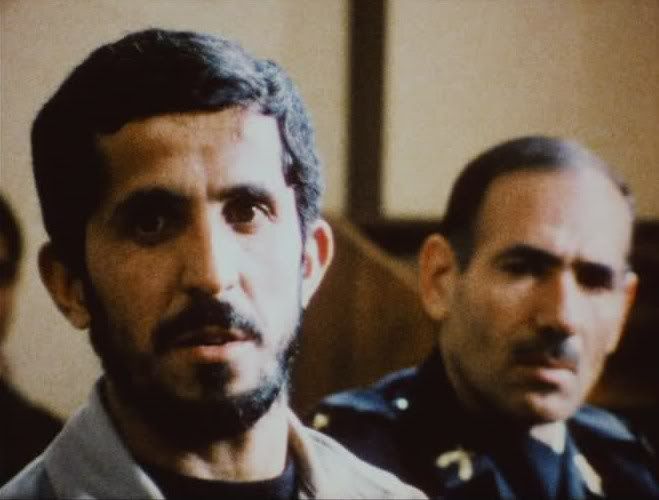

The Dangerous Thread of Things, a rather empty and unsatisfying fragment, the main purpose of which seems to be providing a venue for its actresses to cavort around naked. The plot, such as it is, centers on the couple of Christopher (Christopher Buchholz) and Cloe (Regina Nemni), who are obviously teetering on the edge of a breakup, disaffected and alienated from one another like so many other Antonioni characters. The couple fight constantly, then Christopher meets another woman, Linda (Luisa Ranieri), has sex with her, leaves, and the film ends with both women completely naked on the beach, Cloe dancing at the water's edge until she comes across Linda lying in the sand. The two women stare silently at each other, Linda with a smile on her face, Cloe's face hidden from view by the slightly elevated angle of the shot, and then the film ends.

What this short suggests, perhaps more than anything, is just how thin a line there is in Antonioni's cinema between the examination of emptiness and the perpetration of emptiness. The generous interpretation is that this is another attempt at a study of disconnection, an attempt to show how sex without feeling is just a surface, glossy and perhaps attractive but lacking in depth. The not-so-generous interpretation is that the film is a flimsy excuse for the nude scenes; both women spend much of the film in various states of undress, and several leering shots of the buxom Linda running up and down stairs seem to have dubious narrative or cinematic value in comparison to their making-things-bounce value. This impression is only enhanced by the cheesy synth soundtrack, which adds to the atmosphere of bad vintage porn.

Even so, there are some striking images and some beautifully photographed seaside settings here. At one point, the central couple visits an ocean-view restaurant where the waves of the ocean, oscillating sensuously in a reflection, all but blot out the couple as filmed through the large glass windows of the restaurant. It's an image that recalls, in a vague way, the layered montages of Jean-Luc Godard's later films, with their celebration of natural beauty, their love of light, water and reflections, and their unabashed sensuality. Needless to say, the promise of such images is not followed through here. More generally, Antonioni achieves a low-key pictorial beauty, the beauty of serene landscapes and well-framed shots, like a sequence where Christopher climbs a tall staircase to Linda's home, a very memorable stone tower. Antonioni frames the image to maximize the impact of the geometric design of the tower, which broadens above its first level, creating an upside-down trapezoid, the slanted sides of which overhang the approaching visitor ominously. After Christopher and Linda have sex, Antonioni frames the woman's foot, lounging at the edge of the bed as Christopher gets dressed, a very non-sexual shot that nevertheless winds up being more erotic, in its suggestiveness and its aesthetic beauty, than the softcore explicitness of the love scene itself.

Antonioni is the only one of these three directors to approach eroticism in the most obvious way — through copious nude scenes — and perhaps that's why his film feels so slight. These are generic characters and generic situations, with no time in the short's brief span to develop into anything more, and despite the film's occasional intimations of something deeper and more mysterious — like a weird little interlude in which bathing, naked sirens sing to lure the characters into lust — it never quite adds up to a whole. The same might be said of

Eros itself, which features one great short, one enjoyable one, and one fairly disappointing one, and doesn't make much effort to integrate the three parts in any real way. The anthology would be worth a look for Wong's

The Hand alone, though.