Fritz Lang's M is such an enduring classic that it's hard to imagine a Hollywood remake of it, but that's exactly what director Joseph Losey did, twenty years after Lang's original film about the hunt for a child killer. Losey's remake of M, made under the aegis of the original film's producer Seymour Nebenzal, is extremely faithful to its source, following more or less the same script and at times even recreating scenes virtually shot for shot. It would be easy to dismiss the film as an inferior copy of a classic, and many have: the remake was a flop at release and doesn't have much of a reputation even now. But, though it unquestionably does not match the power of the Lang film, it's still a compelling noir in its own right, transplanting Lang's richly ambiguous social parable to 1950s Hollywood at the height of Red hysteria, which is clearly a prominent subtext here.

For Lang, the film was an anti-death-penalty treatise, a somber and timely warning of the dangers of widespread fear and paranoia, and, of course, a plea to watch out for one's children. For Losey, it's a psychosexual thriller and a parable for the McCarthyite anti-Communism that would soon drive the director out of the United States for the remainder of his career. At one point, in a scene that also appears in Lang's film, two witnesses are arguing over whether a kid's dress was red or blue. Losey adds a key detail: the witness who insists the dress was blue angrily asks the other, "what are you, a Communist?" That loaded question, which was already being casually tossed around at the least pretext in the US of this era, hangs over the film, with Losey subtly reinterpreting Lang's persecution parable, replacing 1930s Germany with 1950s Hollywood to suggest a link between the rise of the Nazi party and the rise of McCarthy. The change in context resonates throughout the early scenes, as random innocent people are persecuted in the streets by a public worked up into hysteria by the child killings.

Losey also subtly changes the film's meaning by making the motive for the child murders implicitly sexual; the film is loaded with sexually charged symbols in a way that Lang's original wasn't. The opening credits show the killer (David Wayne), seen only from behind, approaching little girls, luring one with a string toy that he suggestively pulls and teases with his hands, the framing often hiding the toy altogether so that it's not clear what he's doing, just that he's walking up to a little girl with his hands pumping around at his hips. Another shot shows him turning on a water fountain for a girl, who bends over to drink, her head obscured by the mysterious stranger standing in front of her. Already, Losey, dodging the censors, is suggesting a transgressive sexual component to the murders, a creepy subtext that distances Wayne's killer from the more famous portrayal by Peter Lorre.

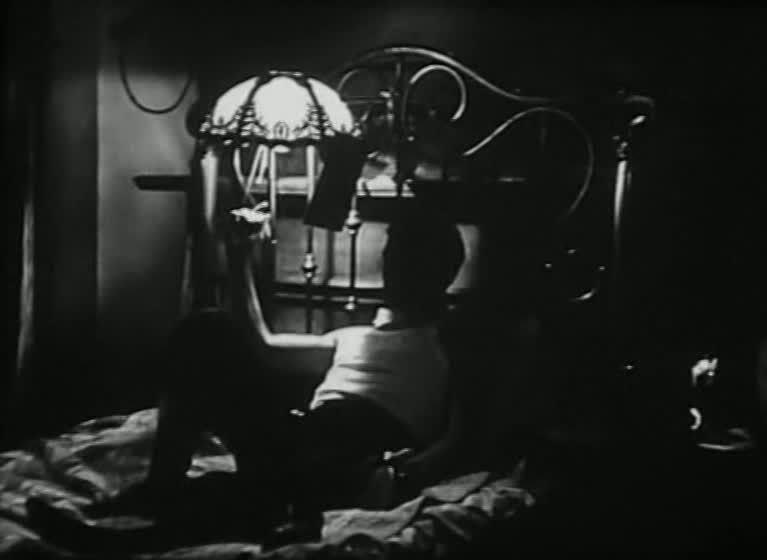

Indeed, Wayne plays killer Martin Harrow with a bland-faced intensity and mommy-fixated sexual dysfunction that prefigures Anthony Perkins' Norman Bates in Hitchcock's Psycho more than it looks back to Lorre. Most chilling of all is the scene of the killer sitting in the dark, his face shrouded in shadow, tightly grasping the dangling cord of the lamp hanging above him, wrapping it around his fist, breathing heavily and pulling his hand further and further up the cord. It's such an obviously sexual scene that one wonders how Losey got away with it, especially when the killer "climaxes" by finally pulling the cord and putting out the light. (That the cord is later revealed to be a shoelace taken from the shoes he collects as fetish objects from his victims only confirms the sexual metaphor.) This is immediately followed by a scene where he goes over to his desk, still panting breathlessly, and begins molding a clay sculpture of a child, wrapping a cord around its neck and squeezing to pop its head off, while Losey prominently highlights the photograph of a matronly older women behind the sculpture, a mise en scène detail that suggests the killer is a sexually frustrated mama's boy.

Such scenes proliferate throughout Losey's remake, suggesting that the killer instinctively makes a connection between masturbation and strangulation; at one point, he finds a wounded bird and picks it up between his fists, its head popping out between his fingers as he squeezes it, before letting it go and sobbing with guilt. His final confessional speech is significantly different from Lorre's version of the scene, too, as he talks about a childhood dominated by his mother's tyrannical insistence that all men are evil and need to be punished — a speech comically punctuated by his aside that she's "a good woman."

In this way, Losey makes the material his own even while largely sticking to the template of the original film. He can't match the overwhelming formal beauty of Lang's film, but he has his own minimalist, low-budget aesthetic that gives his take on this material a rough, shot-on-the-streets realism very different from the shadowy expressionism of Lang's M. Losey shot a lot of footage on the streets of Los Angeles, and staged the climactic search for the killer in the instantly recognizable Bradbury Building, an iconic location for many movies, its angular staircases and multiple levels used well in the scenes of the city's criminal underworld tracking Harrow. Losey's austere aesthetic — only occasionally broken by diversions like the Hitchcockian cut from a mother worrying at home to a screaming, cackling clown — puts the emphasis on Wayne's increasingly unhinged performance and the slightly comic efforts of the police and criminals to catch him. Losey dared to remake a classic, and though the remake is not on the same level as Lang's masterpiece, it should be remembered as a noir classic in its own right, with its substantial differences from its source marking it as a worthy extension of Lang's themes.

"He can't match the overwhelming formal beauty of Lang's film, but he has his own minimalist, low-budget aesthetic that gives his take on this material a rough, shot-on-the-streets realism very different from the shadowy expressionism of Lang's M."

ReplyDeletePrecisely Ed. Losey has his own aesthetic, and much to his credit this "re-make" was negotiated by his own terms during the year he also released THE PROWLER, a seminal noir that uses some of the same ingredients. Kudos to you for the excellent descriptive delineation of the vital sexual context and metaphors in the film and of course for the terrific assertion that this isn't really a Langian encore, but more of an "extention of Lang's themes."

Yes, Wayne's performance is far closer to Perkins's turn in PSYCHO and even to a degree Michael Rooker's in HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER than it is to Lorre's personification. What Losey has done with the film is not really an attempt at a re-make but more a "picture prompt" for creative writing. Show me a picture, and then write about what ideas develop from it.

Losey's M is yet another example of why the eclectic and diverse talent was perhaps the most underrated director in the history of the cinema. Exceptionally written and observed review of an important work.

Indeed, Ed, it takes a lot of testicular fortitude to remake a masterpiece on the level of 'M', but this Losey sounds wonderfully bizarre and incredibly suggestive for its time. Can't wait to see it.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Sam, I'm glad you like this one so much too. Of course David's a big fan as well, but for the most part this film has been forgotten, dismissed for the crime of remaking an acknowledged classic. I love how your phrase Losey's approach to this project: taking Lang's original as a "picture prompt" and elaborating his own ideas in response to the images and scenario that he takes from the original. That's really well-stated and gets to the essence of what Losey's doing here, creating a "faithful" remake in which his own imprint and ideas are nevertheless strongly present. Losey was definitely a signature talent and he's not appreciated nearly enough.

ReplyDeleteMark, I'll be curious to see what you think if you get ahold of this; it's definitely a thoroughly unique and daring film.

An exceellent analysis. Besides the bradbury Building, Losey's "M" features the "Angel's Flight" furnicular rialway in its very first shot. Another unforgettable scene takes place in one of the gigantic apartment buildings that used to be on Bunker Hill. Karen Morley (in what would turn out to be one of her last major film roels thanks to the blacklist) is the mother of one of the Killer's victims. The sight of her helplessly calling her name down the building's enormous stariway is unforgettable.

ReplyDeleteAlso in the supporting cast -- the great Norman Lloyd, who is still with us as he approaches the cnetury mark.

And speaking of Bunker Hill, Losey's "M" would be ideally double featured with one of two other great Bunker Hill films: "The Exiles" and "Blade Runner"

ReplyDeleteThanks, David. All those iconic LA/Bunker Hill locations are definitely well-used here, adding to the film's distinctive atmosphere. And the cast is full of highlights as well.

ReplyDelete