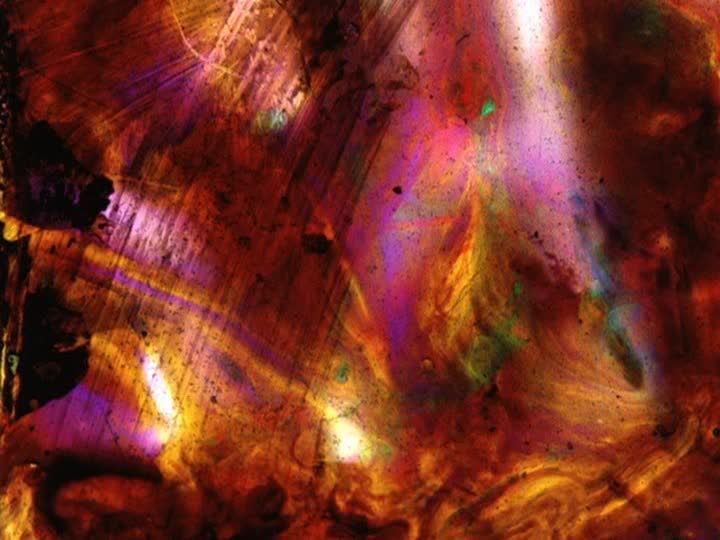

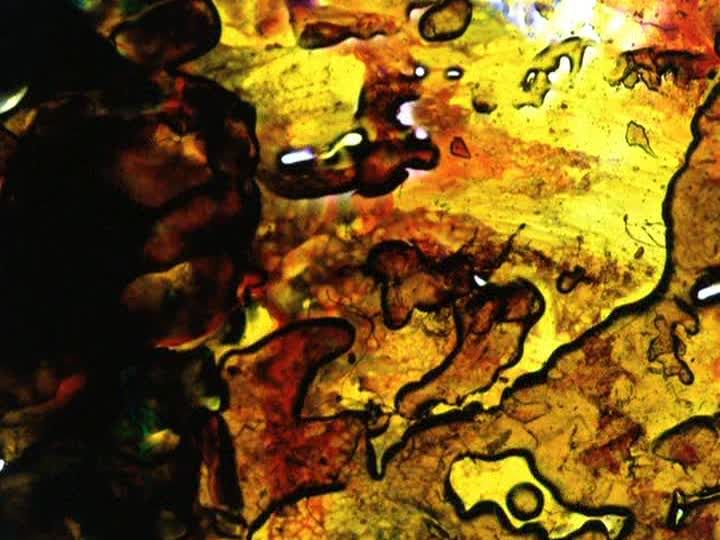

Stan Brakhage's painted films are extraordinarily difficult to write about. These films, more even than Brakhage's films utilizing primarily photographic images, create their own purely visual and abstract language that can not be translated easily into words. The Persian Series, an 18-film series of hand-painted, optically printed works, represents Brakhage at his most resolutely abstract, dealing purely with color, rhythm and form(lessness). The first three films in the series capture different moods, different sensations, while each maintaining a similar palette of bright, thickly clumped paints. Persian #1 is stuttery and hesitant, interspersing bursts of colorful painted hysteria with black-leader pauses, and ending with a few glimpses of blurry color forms that reveal the abstracted photographic foundation that is elsewhere either absent or all but entirely obscured by the dense layers of paint laid atop it. Persian #2 is slow and sensuous, an elegant dance of colors swirling around. Persian #3 is fast and frenetic, introducing more deep blacks and sharp-edged fractal patterns within the rapidly boiling stew of images.

These films are intense and sensually satisfying, suggesting a surprising range of emotions and sensations with their abstract paint blots. Persian #2 opens with an extraordinary sequence that gives the impression of a series of zooms in or out, the "camera" seeming to move forward and then backward. This sequence (achieved via optical printing) creates the impression of entering a tunnel, hurtling down into a wormhole carved out of black space, every color of the spectrum stretched and speed-blurred as the viewer descends towards the center of the whirlpool, only to start pulling away, zooming backwards, rejected by the black hole and its intense swirl of colors. Later in this segment, the images slow down subtly and change to a steady rhythmic beat so that it looks like a rapidly edited montage of still photographs, each seemingly random spill of paint briefly frozen in time, captured in a flash, then flickering away to be replaced by another.

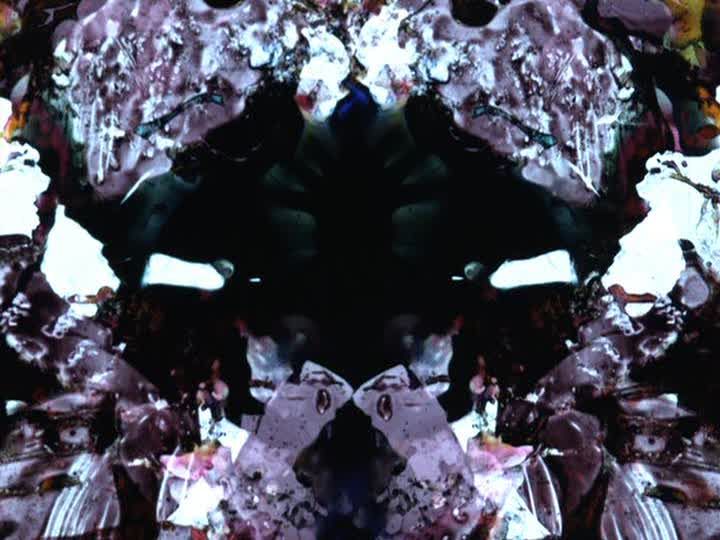

This steady pulsing is entirely unlike the frenzied montage of Persian #3, which starts fast and gradually accelerates to a mad pace that's dizzying and disorienting and utterly hypnotizing. The faster the images fly by, the deeper the viewer is encouraged to stare, the more trapped one feels by the overwhelming density of the montage. The mind nearly shuts down, short-circuited by the tremendous beauty and exhilaration of this sequence. Many of the strangely haunting fractal images embedded within this section subliminally suggest the shape of skulls, with circular forms as eye sockets and nostrils. Mortality is a common subject for Brakhage, who tends to view death as natural, part of a cycle that links birth (Window Water Baby Moving) and death (The Act of Seeing With One's Own Eyes). Here, these hints of death's head skulls are not integrated into the natural world, but provide a context-free evocation of what's hidden beneath the skin, and what is, here, hidden within the constantly shifting, unstable chaos of Brakhage's painted frames.

Such representational associations are perhaps unavoidable even with Brakhage's most abstract work: these meticulously painted frames are like Rorschach ink blots, evoking many concrete forms that may or may not have been intended as associations by Brakhage himself. But whatever can be seen within the chaos of these images is secondary to the visceral, emotional, sensual appeal of the images for their own sake.

It is impossible to watch Stan Brakhage's final film, the two-minute Chinese Series, without thinking about the circumstances in which it was made. As the title suggests, the film was to have been part of a lengthy series of the kind that Brakhage had made before with the Persian Series, the Arabic Series and other serials. He completed only two minutes of the projected series before his death. The film consists entirely of white scratches on a black field: Brakhage carved these marks directly into the emulsion of a filmstrip by wetting the film with his own saliva and scratching with his fingernail. It was perhaps the only method of creation still available to the ailing filmmaker, a process of production founded from the interaction of the filmmaker's own body with the filmstrip.

It is as direct and personal a film as Brakhage ever made, perhaps the ideal of total sympathetic alignment of film and maker that Brakhage had always worked towards. Personal engagement is one of the keystones of Brakhage's art, whether he was using a handheld camera as an extension of his body or foregoing photography altogether to experiment with pasting objects directly onto the filmstrip (as in works like Mothlight) or hand-painting on film. He also often scratched and clawed at the film, as he does here, but rarely so singlemindedly, rarely as the only means of expression through which he acted upon his chosen method. Here, constrained by physical limitations, but also enlivened by aesthetic impulse — he planned to make the entire Chinese Series, however long it would have been, using only these emulsion scratchings — he pares his art down to its bare essence, and it's startling how much of the unmistakeable beauty and mystery of Brakhage's art remains intact in this skeletal form.

The images resulting from this literally hands-on process are as minimal and stark as one would expect: abstract hieroglyphics stuttering across the frame, seeming to spell out words in some indecipherable language. It's calligraphic and graceful. This not-quite-language is a poignant metaphor for Brakhage in the last days of his life, painstakingly (and maybe painfully) scratching out his last communication to the world, the very last images he'd create. There's a simple beauty to these curved white lines, their edges slightly frayed, sometimes densely hatched, sometimes forming just a few scattered, delicate tears in the surface of the film emulsion.

No comments:

Post a Comment