The Last Command is a remarkably clever and poignant Hollywood story, a moving tale of war, doomed love, and the ways in which Hollywood's dream factory can resonate with reality. The exiled Russian Sergius Alexander (Emil Jannings) comes to America as a poor, haunted old man, his head involuntarily shaking, reflecting an old mental trauma. Struggling to survive and make some money, he takes a job as a Hollywood extra, one of countless small-timers waiting in crowds for the chance to be a fleetingly glimpsed face on the silver screen. The irony is that, in Russia, he was a general, a cousin of the Czar himself, until the 1917 Russian Revolution toppled the czarist regime in the name of the Bolsheviks (here referred to as "revolutionists").

Josef von Sternberg infuses this tragic, melancholy story with a beautifully hazy soft-focus aesthetic, honing in on Jannings' heartbreaking performance in sensuous closeups that capture the nuances of the actor's embodiment of this crushed, broken man. Jannings delivers a real tour de force performance, his body shaking uncontrollably, haunted by the war and his humiliation, his face retaining just a trace of his former haughty grandeur in the extra's shuffling walk and heavy-lidded eyes. Then, when the film leaps into a flashback to 1917, in the days leading up to the general's downfall, he seems to be swelled with life and vibrancy, a man of pride and honor, by turns vivacious and intimidating. It's such a great performance because the shell of this man is already apparent in his shattered present-day self.

The flashback reveals how Alexander is outdone by the foolish decisions of the Czar — who seems as out-of-touch as the Bolsheviks claim, unworthy of the service of a truly honorable man like Alexander — and by the plots of the revolutionaries Lev Andreyev (William Powell) and Natalie Dabrova (Evelyn Brent). Later, in 1920s Hollywood, Andreyev has emigrated as well, serving as a director; it's Andreyev who casts Alexander as a Russian general, recreating their real life conflict, a twist that's either utterly cruel or a grand tribute to their rivalry.

The lengthy flashback sequence is especially compelling, as Alexander falls in love with Natalie, even while knowing that she's his enemy and could betray him at any moment. In one fantastic scene, he visits her in her room and notices the handle of a pistol sticking out from under her pillow, but he remains quiet, doing nothing about it, fatalistically waiting for whatever's going to happen. It's doomed romance at its best, embodied in Natalie's sad glances at this man she's growing to respect and maybe even love, while he looks at her with adoration, blinded by her dark beauty and danger. Von Sternberg has a feel for this kind of potent romantic melodrama, highlighting the tiny snub-nosed gun in a charged closeup, and then of course, instead of shooting, the woman throws herself down, her head in her arms. "From now on you are my prisoner of war," Alexander says in a title card, "and my prisoner of love."

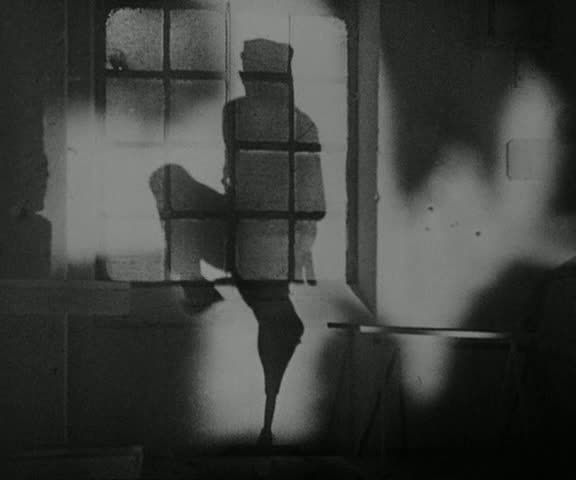

The film reaches its climax with the tragic end of the flashback and a return to the Hollywood backlot, where Alexander is preparing to reprise his historical role in a Hollywood production that Andreyev obviously intends as a propaganda piece for the Bolsheviks. Instead, it becomes Alexander's last chance to shine, his last chance to inhabit the grand role of the heroic general, his face framed against a billowing czarist flag, his eyes wild and wide, losing himself in the past. It's a great moment, the movies providing a kind of tragic closure for this man's sad life, art imitating life in every way. He's still being manipulated and defeated by his enemy Andreyev, in a way, but he's also breaking free, refusing to be confined by the movie's boundaries, briefly making it seem as though he's back at the front, rallying his troops to battle. And then he collapses, and gets a typically Hollywood epitaph from a bystander: "too bad — that guy was a great actor."

That tragicomic send-off suggests that The Last Command is a sly commentary on Hollywood's glossy approach to reality, subtly satirizing the ways in which film's power can deceive as much as inform, reducing the emotional complexity of history as it's lived to extras running around the trenches. But at the same time the movies do have great power, and Alexander's brief moment of fantasy glory suggests that this power is the power to dream, to remake reality, to transform tragedy into a profound aesthetic triumph.