Considering Spike Lee's career-long examination of various American attitudes about race and culture, it's not surprising that at some point he should take a look at the concept of inter-racial relationships. Many of Lee's films have thesis-like ideas at their core, from Bamboozled's satirical dissection of the history of blackface and the issue of race in the entertainment industry, to School Daze's inquiry into divisions within the black community, to the consideration of black/white romance in Jungle Fever. Like so many of Lee's films, Jungle Fever fearlessly looks at race head-on, and like so many of his films, it's messy, provocative, awkward, contradictory, uneven — and unevenly acted — stylistically eclectic, and (over)loaded with ideas. It's never a smooth viewing experience, but then it's clearly not meant to be; its barbs are there to get caught on, to provoke viewers of any race into thinking about ingrained prejudices and the ways in which the history of race in America continues to dominate current-day interactions and relationships between races.

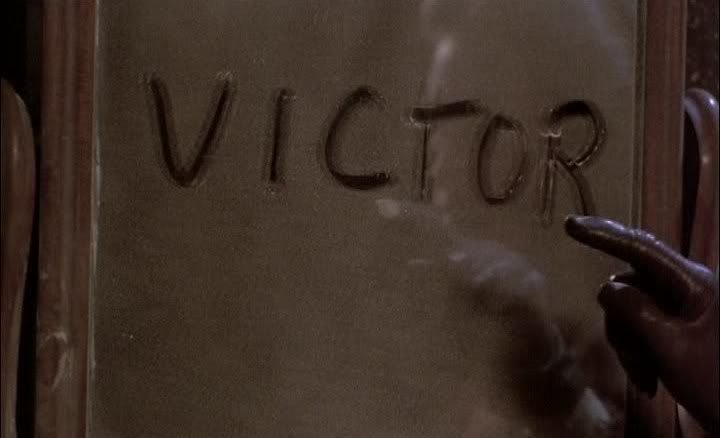

The narrative of Jungle Fever skips all over the place a bit sloppily, but basically it's about the relationship between the black architect Flip (Wesley Snipes) and his white Italian secretary Angie (Anabella Sciorra). Flip is initially antagonistic — he'd wanted his white bosses to hire a black secretary for him — but one night, working late in the moodily lit office, the pair suddenly develop a romantic rapport that leads to a night of passionate sex, even though Flip is in fact married, and seemingly very happily, to Drew (Lonette McKee). There's no explaining attraction or lust, and Flip and Angie simply give in, with predictably problematic results.

Lee places the emphasis on the reactions to this affair more than the affair itself, and at times the film seems to keep forgetting about Flip and Angie for long periods of time. Instead, he detours into scenes with Angie's former boyfriend Paulie (John Turturro) and his crude Italian buddies hanging around a convenience store, expressing racist attitudes while simultaneously lusting after the pretty, educated black woman who visits the store every morning and is friendly with Paulie. Much of the film turns around these kinds of nakedly polemical scenes, shoving character and narrative into the background for scenes like the one where Drew and her friends discuss men and skin color, Lee's camera circling relentlessly around the room while the dialogue, though apparently improvised by the actresses themselves, hamfistedly delivers these ideas.

All of Lee's films have this dichotomy, this tendency to interrupt the narrative for scenes of straightforward political and racial preaching, but Jungle Fever is probably one of his most unbalanced films in that respect: it's not as straightforwardly satirical and polemical as a film like Bamboozled, so its preaching sits uncomfortably with the moments that are more about character or narrative. A prime example is the scene where Flip and Angie visit his parents (Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis), only to have his reverend father deliver a long, to-the-camera address on the history of slavery, miscegenation, and the rape of female slaves by white masters. What could and maybe should be a character scene, about the discomfort of the couple with the reverend's distaste for their relationship, instead becomes just another of Lee's immersion-breaking history lessons, and the central relationship gets shifted more and more to the fringes of the film.

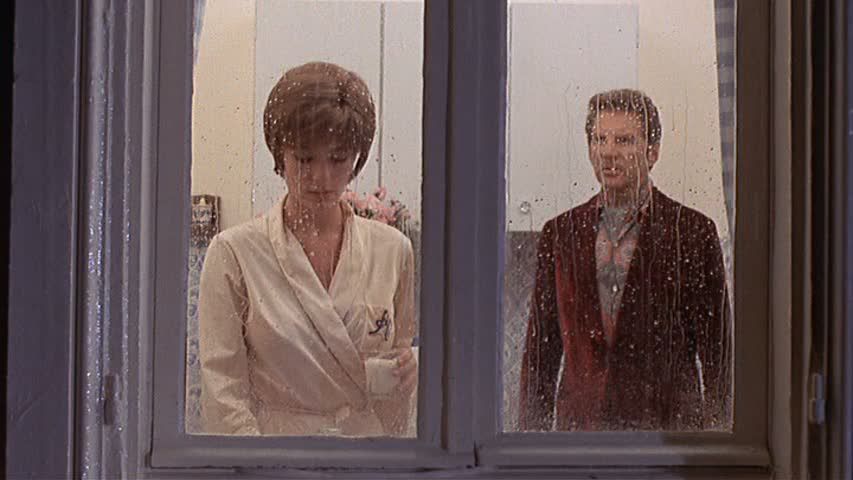

There's still some interesting material here, especially in the way Lee shows the couple receiving prejudice and judgment from all quarters, in both Flip's black Harlem community and Angie's Italian Bensonhurst community. One of Lee's recurring themes is the way that blacks and whites are trapped by race and by the racist history of this country, fated by culture and history to play certain roles, to repeat certain mistakes over and over again. There's some uncertainty here about just how real Angie and Flip's relationship is, regardless of race, but race ensures that they don't stand a chance; it's just too big a barrier to get around. Flip's sudden voicing, late in the film, of prejudiced attitudes about mixed-race children is hard to justify narratively or in terms of his character up to that point, but thematically it makes perfect sense: these ideas, ingrained as they are, are exceptionally difficult to escape, passed down from generation to generation and running through entire cultures, both white and black.

The specter of race makes it impossible to judge this relationship like any other relationship, impossible even to think of Flip's adultery as just adultery rather than a betrayal of his entire race. In that sense, the way the film keeps getting bogged down in polemics and theoretical discussions of race and history is part of the point: these issues are so tangled and complex that this story can't just be a story.