Fascination is a very apt title for a Jean Rollin film. Rollin's ethereal horror oeuvre revolves around the idea of fascination: fixation, obsession, fetishism, the irresistible allure of danger and death, great beauty tangled up with supernatural horror. His cinema repeatedly examines the fascination of the director and, often, his protagonists, with the strange, unsettling, eerie occurrences that haunt his movies. From film to film, Rollin wove together increasingly familiar images and themes that constitute the subject of his fascination: beautiful women naked or dressed only in diaphanous see-through gowns, gothic rural settings, vampirism, seduction, ruined castles lit by candles, secret societies that seem to flicker on the edges of the material world, trapped between states, their exact nature uncertain.

Fascination embodies so many of these fixations that it feels like an ultimate statement of the director's vision; perhaps not his best film but definitely one of his most characteristic, which is why it's also become, within this unusual auteur's cult, one of his most iconic works. The story is, in the usual Rollin fashion, extremely simple, a bare sketch of a scenario used to set up the dreamy, vaguely menacing atmosphere that is the film's true substance. The thief Marc (Jean-Marie Lemaire) betrays the rest of his criminal gang and flees their revenge, arriving at a nearly empty rural estate where the only residents are a pair of girls, Eva (Brigitte Lehaie) and Elisabeth (Franca Maï). Marc holds the girls prisoner while fending off his gang's attacks, but it soon becomes clear that if this is a hostage situation, who's the hostage and who's the captor might be the reverse of what Marc thinks.

Certainly, Marc believes that he's the one in control here, but a driving theme of the film is the exploration of power's relationship to gender and sexuality. Marc is a sneering, arrogant jerk, dominating these two girls from his position of power, waving his phallic gun around as a symbol of his sexual and physical dominion over them. Eva and Elisabeth sometimes play their expected roles, cowering in fear before him, but soon their show of fear and submissiveness gives way to a much more playful, mocking attitude, skewering his belief in his dominance, suggesting that they're really the ones in control. While taunting him with the prospect of sex, they actually go to bed together, in a scene of sumptuous softcore eroticism that could've come directly out of one of Rollin's adult productions. When Eva does give in to Marc, she's quite open about her motives: she wants to keep him there until nightfall, using her sexuality to lure him into what increasingly seems like a deadly trap.

There's clearly something sinister going on here, even if the hapless, arrogant Marc laughs off all the premonitions and warnings about the fate awaiting him once midnight strikes. Elisabeth, who seems slightly less unhinged than her compatriot, warns Marc that he should flee, that something horrible is in store for him that night. Anyone who enters the orbit of these girls is trapped within "the universe of madness and death," she says, clutching the gun she's stolen from their guest. Later, the girls are joined by more members of what seems to be a blood-drinking, Satan-worshipping club of wealthy bourgeois women, but Marc still doesn't catch on. The audience is a few steps ahead of him anyway, having been warned more explicitly by the gorgeously morbid prologue in which these women daintily drank ox blood from goblets while standing in a slaughterhouse, their frilly dresses dragging in the bits of cartilage and bloody flesh strewn across the reddened floor. The leader of this club, Hélène (Fanny Magier), warns Marc, "Beware, death sometimes takes the form of seduction," but even then he treats this night like a game, so secure in his masculine superiority that it never occurs to him that he's not in control, that he's become the prey rather than the predator.

The film's most enticing predator is undoubtedly Eva, who is especially terrifying in a sequence where she methodically, ruthlessly kills the members of Marc's gang, stabbing one man in the side during sex and then prowling after the others with a black robe billowing around her naked body, a scythe held threateningly in front of her. She's a sexy, seductive grim reaper, blonde death with a vicious blade that easily outdoes Marc's puny gun as far as penetrative phallic imagery goes. Rollin had first featured Lahaie in one of his bills-paying adult film productions, then given her a small but unforgettably intense role in his moody zombie classic The Grapes of Death.

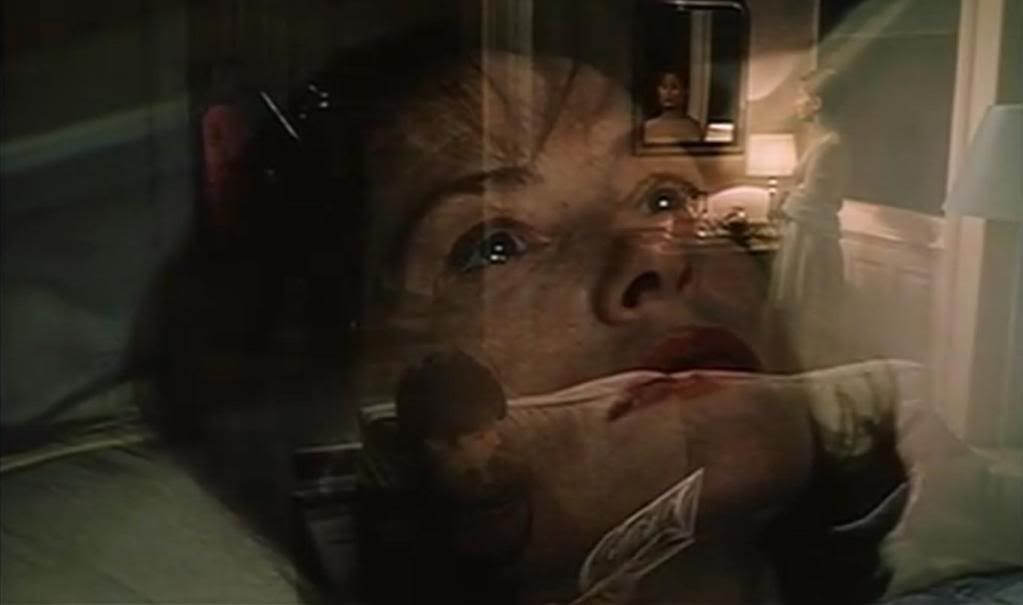

Here, she magnifies and extends the sexy insanity of her part in that film, killing with her mouth locked in a horrible/alluring rictus grin, baring her teeth and smiling as she slashes throats with her reaper's blade. There's something feral about her, an animalistic quality that somehow only makes her more appealing, and more unsettling. Rollin captures her in evocative closeups in the moments before the kill, her eyes above the blade, her lips below it. Rollin seems to be asking, which is more dangerous, the scythe or the girl who wields it? Her alluring lips, her piercing eyes, they're as deadly as a knife to the guts, and with her, one leads to the other — her beauty and sexuality are lures into death and oblivion.

The strange attractiveness of death and perversion are at the core of this film, which perfectly captures the fascination that these beautiful, deadly women hold for their victims. Rollin makes the girls and their surroundings ravishing: the mansion, lit by candelabra, is lavishly decked out with fancy furniture and paintings, the surfaces of which Rollin's camera frequently probes whenever it's not being distracted by the lovely anti-heroines. Sensual and chilling in equal measures, Fascination is a nearly comprehensive catalogue of Rollin's obsessions and themes, exploring the appeal of the macabre and the impotency of male power through this hypnotically languid horror tale.