Zelig marked a very unexpected departure for Woody Allen, who had ended the 70s with a series of increasingly introspective and psychological films that seemed to directly reflect his own modern Manhattan milieu. Then, following 1980's Fellini tribute Stardust Memories, he retreated to work on two new projects simultaneously. One was a farcical period piece based on the work of Bergman, Shakespeare, and Renoir (A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy, as already discussed), and the other was a faux-documentary set in 1920s, about a man who transformed himself to be more like whoever was around him. Allen himself plays Leonard Zelig, one of his most memorable, inventive, and deeply symbolic characters. Zelig was so chronically insecure, and so eager to fit in with a world that seemed to hate him, that he developed a "condition" whereby his personality and physical appearance would alter in response to whoever was around him. For a time, he is happy to blend in everywhere — he poses as an aristocrat, a black jazz man, a Yankee baseball player — but his talent is soon discovered and he is placed under medical scrutiny.

Allen was committed to making this project appear to be a true documentary, and to that ends he filmed with 1920s equipment and lighting, scratched the negatives, and in some cases inserted himself, with a blue screen, into vintage footage of Babe Ruth, Adolf Hitler, and other 1920s famous figures and moments. This latter technique, of course, is predictive of its much later use in Forrest Gump, which also had a symbolic character passing through the moments of history via blue screen magic. The difference is that the later film is deeply nostalgic, sentimental, and conservative, whereas Woody's is witty, intelligent, and much deeper than its surface laughs would indicate. It also presents a diametrically opposite idea about life to the one found in Gump — where Gump excels by blindly obeying what people tell him, Zelig only comes into his own when he develops his own personality and stops trying to be like everyone else. As the film itself points out, in documentary voiceover, Zelig is a lightning rod for all sorts of metaphorical interpretations. He is the prototypical Jew, desperately trying to assimilate in his home culture. He is, more broadly, the American immigrant, also forced to smooth out his differences in favor of the conformity of the wider culture. And, as the film's final segment drives home, he is the average man unable to express his own opinions and ideas for fear of ostracism. In the film's last 20 minutes, when a distraught Zelig finds himself in Germany, happily adapting himself to the Nazis around him, the film makes it clear that conformity is at the root of fascism and oppression. Zelig started out on this path because he was afraid to admit he hadn't read Moby Dick when someone asked him; eventually, his conformity led to him "fitting right in" in the early days of fascist Germany.

It's important to emphasize that despite these deeper implications, Zelig is a very funny film. Woody's attention to detail allows him to flawlessly recreate the texture of the 1920s, as filtered through documentary techniques. And he packs every inch of this imagined past with all manner of gags and jokes. The documentary format allows him so freedom and looseness in his narrative, a step back from the tighter storytelling of his relationship comedies like Annie Hall. Structurally, this film looks back more to Woody's earliest era, when films like Bananas were essentially just collections of loosely related scenes whose primary purpose was to get the joke across. The disparate scenes come fast and furious here, with a crackling pace that makes the film seem a lot denser and longer than its slim 79 minutes. This is classic Woody, a wonderfully sophisticated film that approaches weighty ideas with a quick wit and lightness that truly sets Allen apart among comedic directors.

Even as I continue my odyssey through Woody's oeuvre, I keep returning to Fassbinder's equally massive filmography. Tonight it was his very first feature, 1969's Love is Colder Than Death. What's remarkable here is that Fassbinder seems to have come out fully formed, not only exploring many of the themes and ideas which would have continued importance for him throughout his career, but in full possession of the aesthetic means to express those ideas. True, he had directed a number of stage plays (including this one) before turning to film, but he clearly adapted to the cinematic medium with ease. Fassbinder himself plays the lead, Franz Walsch, a petty gangster who lives with his prostitute girlfriend Joanna (Hanna Schygulla), and whose life is disrupted by the arrival of his friend Bruno (Ulli Lommel). Bruno's quietly magnetic personality clearly attracts both Franz and Joanna, and together the threesome embark on a violent crime spree before a jealous and distrustful Joanna betrays Bruno to the police.

The film is bathed in the aesthetics of the French New Wave, which was an important early influence on Fassbinder's work. He even dedicates the film to French directors Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, and Jean-Marie Straub, and the unmentioned Jean-Luc Godard seems an especially important influence here. There's more than a little similarity to Godard's own debut feature, Breathless, which also featured a matter-of-fact deployment of violence and a distancing deconstruction of Hollywood gangster cliches. Lommel's character, in his cocked fedora, trenchcoat, and dark sunglasses, looks like he stepped right out of a French gangster movie, maybe Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Samourai from 2 years prior. But despite these similarities and a clear lineage of influence (Hitchcock also comes up, with a reference to the cop from Psycho), Fassbinder's style is, on balance, wholly his own. The film's editing has an odd, halting quality to it. Scenes stretch on for a long time with very little happening, remaining static, then suddenly there will be a flurry of activity and a rushed line, and the scene clips off abruptly, as though Fassbinder was suddenly reluctant to linger any longer on this moment. Because of this, the film tends to alternate between engagement and distancing, with long static takes keeping the viewer at arm's length from the characters before a sudden outburst of emotion or activity draws the audience back into the story — and just as suddenly, it's over and on to the next scene.

Just as Fassbinder's proficiency with the dialectic of distance/emotion is fully formed at this early point, he's also already exploring his interest in the power dynamics of relationships and the ways in which outside forces impinge on the individual. There's also a strong undercurrent of repressed homosexual desire here, another theme that would run through the subtext in many of Fassbinder's less overtly "gay" pictures. This is a remarkable debut, a glimpse at the future Fassbinder and a wholly satisfying film on its own merits as well.

This must've been a good day for first films, because I also watched Chocolat, the directorial debut of Claire Denis, surely one of the finest of today's filmmakers. Denis, like Fassbinder, also seems to have come out fully formed in her debut, although for a different reason — before directing Chocolat, she was an assistant on the sets of directors like Jim Jarmusch, Wim Wenders, and Costa-Gavras. This background shows on her self-assured debut, which flows with the smooth and deliberate pacing of a seasoned professional who knows what she wants to say. Denis today is known for her collaboration with Agnes Godard, who became her regular cinematographer only shortly after this, and served as a camera assistant on this film. The cinematography here lacks some of the visual flair that Godard brought to Denis' films, but the imagery of northern Africa is undeniably beautiful anyway, and moreover has the same sense of carefully modulated time that is present in all of Denis' work.

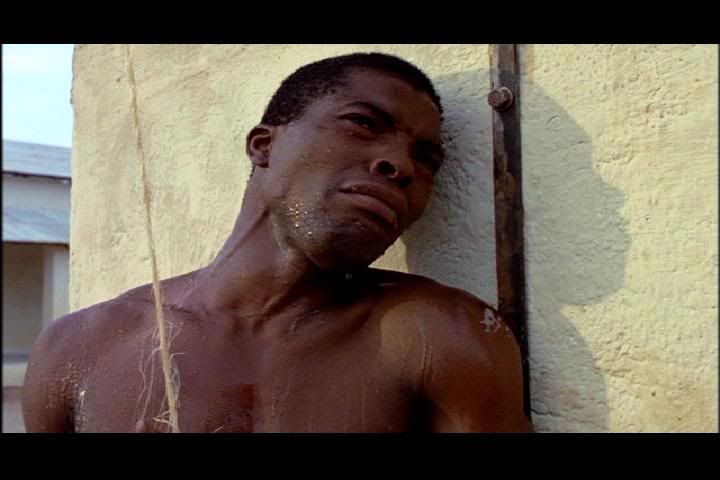

Denis' films always have a surface calm and quiet that belies the often intense emotions boiling away beneath that surface. This is certainly the case here, as Denis probes into the racial tensions inherent in late-colonial Africa. The film concerns a French colonial governor and his family living in Cameroon, and in terms of plot, Denis fans shouldn't be surprised to learn there isn't much there. The governor is often gone, leaving his beautiful wife and young daughter to fend for themselves, watched over by their black manservant Protée. There is plenty of incident, presented with Denis' typical elliptical editing, but not much that ever adds up to a story in traditional terms. Instead, Denis allows the simmering erotic desires and the tension of the racial divide slowly come to a head without ever quite erupting as you might expect. Denis never lets her story verge into melodrama, and she never makes her points overtly — everything here exists in the subtext, since the surface is exactly the placid and formal milieu required by this colonial upper-class setting. And what a rich subtext, in which sensuality, racism, and colonialism intrude subconsciously upon every aspect of daily life, upon every interaction, no matter how trivial or seemingly innocent. It's a dazzling debut, and like all of Denis' films, it's much easier to enjoy than it is to talk about — her way of presenting her ideas is so subtle, so gentle, that they almost seem to seep into the viewer without notice.

Finally, the last film of the evening was Edgar G. Ulmer's B-noir Detour, a fine example of the kind of gritty, true B pictures that were so common in the 40s and 50s. The film is a lean 68 minutes, obviously designed to precede a more expensively produced main feature, and these humble origins show in every inch of film here. Nevertheless, despite the cheap sets, rough transitions, and shoddy back projection, there's a raw energy and vitality that elevates it above many of its contemporaries. The story is simple, following the innocent and gentle-natured Al Roberts (Tom Neal) hitchhiking across the country to meet up with his girlfriend in California. Along the way, he's picked up by a shady bookie, who promptly dies when he falls asleep and falls out of the car. The hitchhiker knows he'll be blamed, so he hides the body and takes the dead man's car and identity, planning to ditch both once he can get to a big city and disappear. His plans are disrupted, though, when he himself picks up a woman hitchhiker (Ann Savage), who happens to be the same woman who was picked up previously by the dead man.

She of course knows that Roberts is not who he claims to be, and she uses this knowledge to take control of him, taking all the money he got from the dead man and keeping him prisoner in an apartment they rent together. Savage dominates this film, delivering a performance of totally uncompromising fierceness. Her character is the ultimate femme fatale, driven by greed and a total disregard for others. When she first rounds on Roberts with her accusations, it's a truly terrifying scene, as her flashing eyes and sneer seem ready to rip him to pieces just with a look. Neal can't do much to compete with this scenery-chewing tour-de-force, but he ably portrays his character's innocence and sad resignation to his fate; his sad eyes convey depths of emotion whenever the camera closes in on him. This is no masterpiece: its plot is sometimes slack or frankly unbelievable, and its aesthetics are ragged and uneven. But in terms of pure energy and mood, it's hard to top this.

No comments:

Post a Comment