Joseph Losey's Mr. Klein, made in France during the director's long post-blacklist exile from the US, is a chilling (and chilly) parable about identity, fascism, exploitation and oppression. Set during World War II in occupied France, the film centers around the titular Robert Klein (Alain Delon), an art dealer who exploits the situation in his country by buying cheap paintings from fleeing Jews, who are mostly looking to get just enough money to escape the increasingly restrictive Nazi regulations. Klein is indifferent to those he exploits, caring only about his own luxurious life, until one day he receives a Jewish newspaper addressed to him. He realizes, soon enough, that there is another Robert Klein in Paris, a Jew disguising himself as a collaborationist Frenchman, and he becomes obsessed with ferreting out this other Klein, this mirror image alter-ego. This, in turn, attracts the attention of the Vichy police, who become suspicious of this Klein as well.

Losey's mise en scène is methodical and austere, evincing a cold distance that suits the abstract story of a man losing himself in a doppelganger he never quite meets. The multiple shots of Klein standing alone in a tightly wrapped overcoat and hat, isolated even in crowd shots, deliberately echo the hyper-cool image of Delon from his iconic role in Le samouraï. He wanders around, earnestly staring with his cold blue eyes, encountering various mysterious figures who fail to aid him in his search — with an impressive supporting cast populated with the likes of Jeanne Moreau, Juliet Berto, Francine Bergé, Michael Lonsdale and Rivette muse Hermine Karagheuz. The film's most stunning scene, however, is its first, a seeming non sequitur in which a doctor examines a naked female patient, clinically reciting various attributes that suggest an "inferior race." The cold horror and bureaucratic precision of this scene sets the tone for the remainder of the film, immediately establishing Klein's milieu as one in which human beings are treated like animals, their teeth examined like racehorses — an association recalled in the next scene, when Klein's pampered mistress examines her own teeth while applying lipstick. Losey's unforgettable film is concerned with this matter-of-fact horror, and with the oblivious mindset that ignores such things, insisting that everything is normal, everything is OK, even in the face of tremendous evidence to the contrary.

10 comments:

This is Losey's best film, and Delon's as well. You're quite right about the opening scene. It's incredibly shocking to see a human being treated this way. Yet we know this happened and we know what's coming. What's doubly upsetting is that the woman still holds out hope she'll be spared. She won't.

As for Delon there's no actor alive who could do this part. It's not simply that he's the embodiment of the suavely sinister, but as film acting requires bringing out everything to the surface of the face Delon is expert at presenting human duplicity. It's not simply that Klein offers a "self" to the world that's constantly shaded -- its' that he hides from himself as well. See Delon in everything from Plein Soleil, La Piscine, Un Flic and (Losey's underrated) The Assassination of Trotsky for the evolution of this persona. But here it reaches its apex -- at the film's end. For Delon's Klein truly thinks he's escaped -- even though he's headed straight for the extermination camps.

All the other actors in their turns (particularly Moreau and Berto) are superb. And the anti-semitic cabaret (performed by the "Grand Eugen" troupe) must be seen to be disbelieved.

Yeah, this is my favorite Losey too, definitely his masterpiece. I love your analysis of Delon/Klein as someone who hides from himself, wrapping himself in self-delusion. That theme is especially embodied here in the idea that there are two Kleins, even though as the film goes on it increasingly begins to seem like the second Klein exists only in the mind of the first, an embodiment of his paranoia and fear.

In this Klein resembles Poe's "William Wilson" -- who Delon played in Louis Malle's episode of Histoires Extrordinaires (aka)Spirits of the Dead )

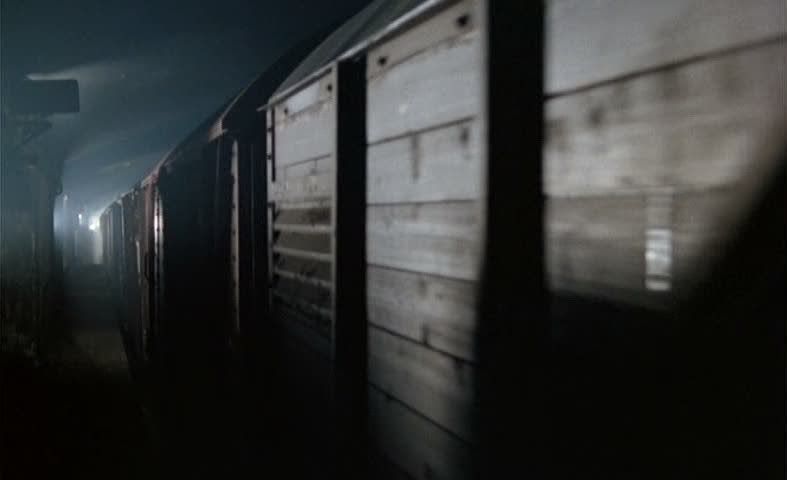

Great evocative summary Ed, getting at the core of the film in a scant two paragraphs and a few screen captures. I especially like your horse metaphor in the films opening, a sequence I've always thought sees its natural outcome at the films close when the hordes of 'horses' are packed into a stable train car as if they are livestock of some sort. It's a film that relies on our intimate knowledge of the events, knowing what is probably in store for all involved.

I think it is one of Losey's best pictures, but not his best. I happen to be an immense Harold Pinter fan and that trio they did are just all sublime films. THE ACCIDENT is savage and sublime, THE SERVANT surreal and subversive, and THE GO-BETWEEN is prim and proper but also quite horrific (many consider it a horror film). All those films, in that order, I'd consider Losey's best, then this one and probably THE PROWLER.

I've never seen THE CRIMINAL but know that it is highly rated as well.

I love Delon. I remember when I was little, my mother looked at all his movies. Looking at all the films I began to admire him. It's a great actor.

And a very complicated and dangerous human being. Go forth and "Google."

Losey's The Criminal (aka. The Concrete Jungle) is not bad. Script by Alun Owen (who went on to write A Hard Day's Night) and a great performance by Stanley Baker.

Thanks, Jamie. You're right about how Losey relies on our knowledge of the period to build this incredible sense of dread. And the not-so-subtle horror of scenes like the opening add to the claustrophobia and tension. It gives a real edge to Klein's aimless confusion. I love Losey's Pinter collaborations, too, of course, though I haven't seen The Go-Between (or The Criminal) yet. He's such a fascinating director. One that doesn't get mentioned much is La truite, a very weird and savagely funny film that makes the phrase "cold fish" seem like a hilariously literal metaphor.

Alexander, Delon is one of the greats. Always such a magnetic screen presence, even when so many of his iconic roles seem to turn on projecting blankness and ennui.

La Truite has one of my all-time favorite movie lines, delivered with appropriately devestating aplomb byt eh great Jeanne Moreau: "Heterosexual, homosexual -- people are either sexual or they're not!"

Just my two centimes...

The way Robert Klein deals with the painting in the second scene mirrors the way doctors at the hospital deal with people : art is an object of anatomy, a thing that can be precisely - and profitably - studied, measured, handled and accounted for. Something devoid of humanity. The shot of the couple after the wife has been examined is echoed by the shot where the seller of the portrait looks for the last time at his family's treasure. "For me, it's a job" says Robert Klein - this line comes all the way from the Nuremberg trials.

Monsieur Klein is the story of a predator in a predatory environment (much like Don Giovanni, The Servant, Accident, The Damned, Eva, Secret Ceremony, even the Go-Between and the Romantic Englishwoman). Alain Delon plays a perfect example of what Gilles Deleuze called the 'static violence' of many of Losey's leading characters : a polite, silent man dominated by the impulses of a bird of prey. At the cut at the end of the second scene (the sale of the portrait), the colors of the painting in Klein's corridor perfectly match the color of the tapestry auctioned in the opening of the third scene. The tapestry depicts a vulture, and the cabaret audience is made of scavengers.

As others pointed out above, the private investigation has little to do about who the 'other' Klein might be: Robert Klein has been hiding from himself and now becomes engaged in a quest for his own identity. A totally selfish quest of course, especially considering the circumstances, yet an universal quest that can trigger some of the viewer sympathy. From a man trying to prove who he isn't, he turns into a man trying to grasp who he is. Yet he makes little progress, as he tends to relate everything to himself (Moby Dick, the 'dutch gentleman', the woman) and still doesn't realize that he cannot reach humanity unless he acknowledges the 'absolute otherness' of other humans.

The very dark irony being, of course, that he might come to that point through his shared ordeal with the Paris Jews, finally becoming at the same time free and dead - along, alas, so many people. My guess is the main point of view here might not be about the indifference of European societies, but rather about their pretense to succeed in defining the others, and the catastrophic failure to which this pretense leads. I don't want to sound grim, but I'm afraid it is something we haven't got rid of.

Thanks for the lovely reading of MK. I took some M. Klein images for a post on the Blowup Moment: http://theblowupmoment.blogspot.com/2011/07/m-klein-joseph-losey-1976-kodak.html

and there's one here in a context of Nazis and maps, on the Cine-Tourist:

http://www.thecinetourist.net/1/post/2011/07/115-yoyo-pierre-etaix-1964.html

Roland-François Lack

Post a Comment