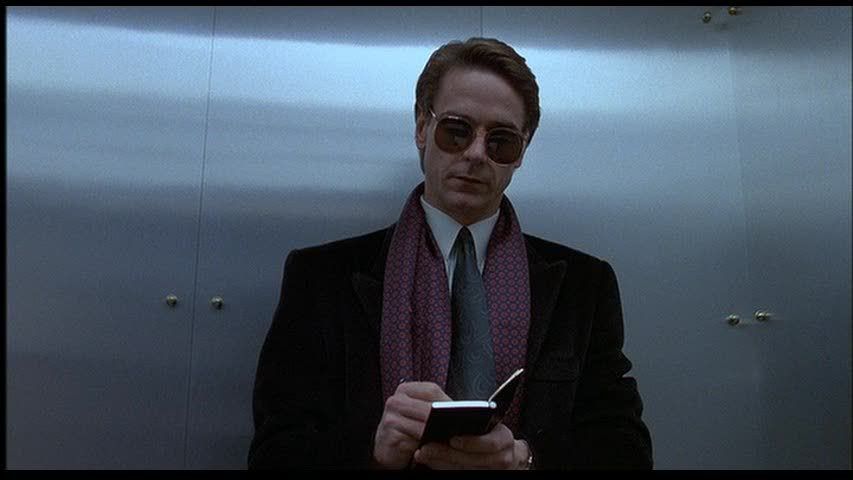

The Fourth Man, Paul Verhoeven's final Dutch-language film before his sojourn to Hollywood to direct films like RoboCop and Basic Instinct, is a typically delirious fantasia from this gleefully controversial director. Awash in lurid Christian symbolism and a fluidly multisexual eroticism, the film is a nightmarish adventure that would do David Lynch proud: a man's dreamlike, elliptical journey into strange territory, guided by a possibly deranged imagination that finds unexpected patterns and recurrences in his experiences. The writer Gerard Reve (Jeroen Krabbé) travels to a distant town in order to give a lecture. Once there, he meets the mysteriously alluring but icy Christine (Renée Soutendijk) and spends the night with her, having sex with her while praising her for her boyish body. In the morning, Gerard plans to leave but is stopped by the discovery that Christine's regular lover is a young man named Herman (Thom Hoffman), who Gerard had previously seen and desired during a brief encounter at the train station. In the hopes of seeing more of Herman, Gerard stays on, supposedly working on his next novel but mostly just drinking and bouncing around within Christine's palatial home, which is adjacent to her lucrative beauty salon.

Christine, it turns out, is a "black widow," a precursor to Basic Instinct's Catherine Trammell, another icy blonde with a predilection for devouring her mates. Just in case Christine's deadly undercurrents aren't apparent from the sinister, gloating smile she displays when she realizes Gerard is going to stay with her, Verhoeven layers on the unsubtle symbolism: the opening credits feature a nasty-looking spider crawling across Christian iconography and wrapping its victims in a web cocoon, while the sign for Christine's "Sphinx" beauty parlor keeps flashing out to read "spin" instead, the Dutch word for "spider." The film is so packed with tongue in cheek visual symbols like this that half the fun is in spotting the references and unraveling the densely tangled webs of meaning. Gerard's story is a confused mingling of Christian sin/redemption and gay fetishism, no more so than in the hilarious sequence where Gerard goes to church and finds a vision of Herman, clad only in a speedo, nailed to a cross like Christ and waiting for Gerard to unclothe him.

Indeed, Gerard's entire story is driven by dreams and visions, by his writer's imagination, which can't help but spin out wild variations on whatever is in front of him. He's obsessed with death. As soon as he steps off the train, he encounters a funeral party that he's at first convinced is for him: the letters on a wreath seem to spell out "Gerard" until the funeral director unfolds the banner, revealing an entirely different name. Later, Gerard makes the same mistake with a letter to Christine, baffled to find it seems to be from him until he smooths out the paper and finds it's from Herman. Throughout the film, appearances can be deceiving, and often the illusory surface falls away to reveal something else. In one of Gerard's dreams, a woman (Geert de Jong) who keeps appearing in both his dreams and his waking life seems to be pointing a gun at him, but then turns the "barrel" to the side to reveal it as a harmless key instead. At another point, a door Gerard sees in his dream, with a distinctive cross-shaped design, is mirrored in a cabinet at Christine's house, which holds film loops chronicling her three dead husbands. Later, Gerard stumbles upon the real door and location from his dream, discovering that it is the crypt where the ashes of Christine's husbands are kept. Dreams and reality weave into one another: a literal resting place, a grave, is echoed in a film vault, which also retains the traces of dead men.

Gerard's portents and nightmares, his outlandish fantasies, lead him through the film, slowly discovering the truth about Christine even as he tries to seduce her lover. This writer's rich fantasy life provides Verhoeven with ample opportunity for visual indulgence, and there are several marvelous tour de force scenes, packed with overt Freudian symbolism and references to the director's cinematic forebears. Early on, Gerard is pulled into a poster in a train car, a photo of a hotel: he wanders into the photo, steps into the eerily empty hotel and walks through its corridors clutching a key, looking for his room number. When he gets to his room, however, the number on the door turns into an eye which stares at him for a moment before oozing out of its socket with a trail of blood and slime behind it — foreshadowing the film's gory conclusion. The whole sequence is reminiscent of Kubrick's The Shining, with its haunted hotel and endless tracking shots down creepily barren hallways. The connection becomes particularly apparent when Gerard is snapped out of this disquieting fantasy to the realization that the poster he was staring at has been streaked with blood — or, actually, tomato juice leaking from a woman's bag in the overhead compartment.

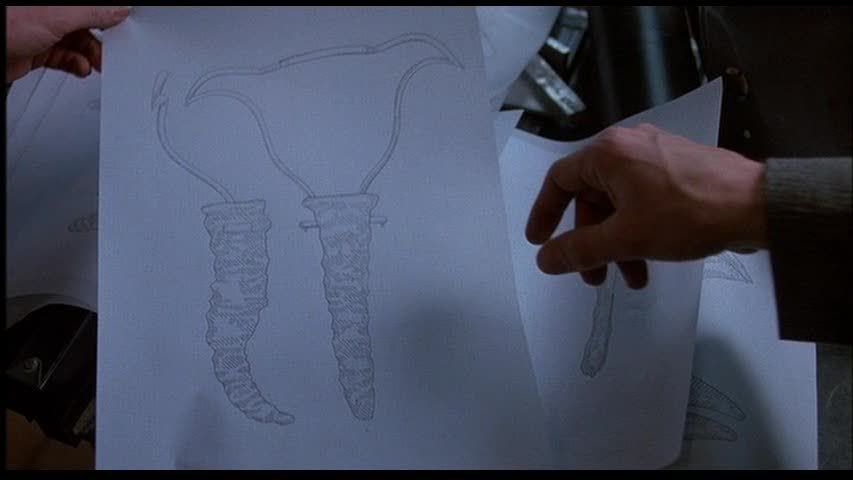

Later, during an even more horrifying sequence, Gerard wanders down a tree-lined path in pursuit of a woman wrapped up in a cloak — the same woman from the train and elsewhere, who he comes to think of as the Virgin Mary, sent to save him. She gives him a key and leads him into a crypt where three slaughtered pigs hang above buckets, their blood dripping out of their flayed carcasses. Finally, Gerard seems to wake up in bed only to experience an even more Freudian nightmare: he is literally castrated, his organ snipped off with Christine's scissors. The scene recalls both the most excessive moments of Fassbinder's oeuvre — especially the slaughterhouse sequence of In a Year With 13 Moons and the hallucinatory epilogue to Berlin Alexanderplatz — and the languid, dreamlike imagery of Maya Deren's avant-garde classic Meshes of the Afternoon. These disparate influences bubble through the film, much like the blending together of ordinarily incompatible elements like religious allegory, dark comedy and the sexual thriller genre.

Of course, this confusion of moods is typical of Verhoeven: he's definitely a genre director but is seldom content with mining just one genre at a time. The Fourth Man is a fun, ridiculous farce, a self-referential loop of a movie that revels in the blasphemous, erotic chaos of its imagery. The film evokes a multitude of potential readings, dealing as it does with gender confusion, male fears and insecurities about women, the complicated intersections of sex and religion and the ways in which ideas about death color and inform all of these things. Verhoeven irreverently throws all these loosely developed ideas together, allowing them to flutter like ribbons through his colorful, visually sumptuous and unforgettable entertainment. Verhoeven defies the usual template of the genre director who smuggles his themes into his films beneath the cover of surface thrills and shocks. With Verhoeven, surface and subtext are flamboyantly united: the ideas of his films are impossible to miss, scrawled as they are with the brightest possible crayons right on the most apparent layer of his films. Verhoeven is not a smuggler, preferring instead to amplify his subversive subjects, to make them entertaining in themselves. In Verhoeven's best work (a long list which surely includes this stunner) he is able to take the subversive and mold it into something garish, beautiful, exciting and viscerally entertaining. He takes the dark undercurrents of other films and lets them out into the sunlight to play.