The Heckling Hare is a fairly typical Bugs Bunny cartoon animated under the able direction of Tex Avery, though the film doesn't have much sign of the frenzied energy Avery would later become known for. It runs through the usual Bugs gags, setting his wily charm against the incompetent pursuit of whatever poor creature is trying to catch the wascally wabbit this time. The adversary here is one in a long line of sad-sack dogs, with droopy ears, a pointer's tale, and a malleable, expressive face. Warner cartoons frequently revolved around delayed reactions, and Bugs' appearances often had a special variation on this trope, in which a hunter of some kind chats amiably and unsuspectingly with his prey before abruptly realizing who he's talking to. This schtick is best known from the Bugs shorts with Elmer Fudd, but it cropped up frequently with the whole Looney Tunes stable, and especially in the many cases where Bugs is futilely pursued by a much dumber adversary.

As the Bugs versus dumb enemy shorts go, this is somewhere in the middle tier, an average cartoon that runs through the whole array of recycled gags familiar to anyone who's watched any number of Warner cartoons before. The dog chases Bugs down a hole, while Bugs nonchalantly climbs out of a nearby second hole to make his escape. Bugs assaults the dog with slapstick violence, plants a juicy kiss on his lips, and races off. During a swim, Bugs calmly waltzes through any number of water hazards, avoiding rocks and diving only into deep-enough water, while the dog continually gets battered and halted by the obstacles in his path. The film's only unique variation comes with a scene where Bugs begins mimicking the dog's facial expressions, frustrating his pursuer into trying out increasingly outlandish faces to try to trip up Bugs. Avery basically uses this as an animation showcase, an excuse to run his characters through a barrage of funny faces and rubbery poses, and it's a nicely executed tour de force with some great gags. The ending recycles another typical Warner device, as it blithely breaks the fourth wall to come up with an ending: both Bugs and the dog are hurtling towards the ground, having fallen from a great height, and then abruptly pull up short at the last moment, gently touching down on their feet. "Fooled ya," Bugs drawls, and the cartoon ends. It's a funny, unexpected moment, but it lacks the subversive punch of other fourth wall shattering moments in the Warner oeuvre — it seems more like the writers were stumped for a way to end this umpteenth cookie-cutter Bugs cartoon and simply used the device as a clever cop-out.

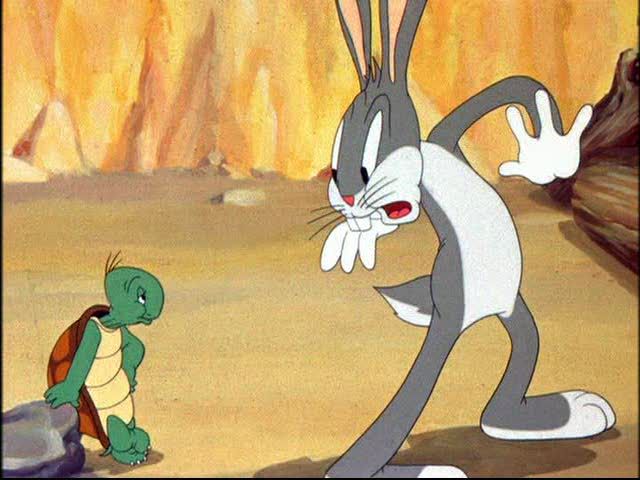

Tortoise Beats Hare is yet another Bugs Bunny cartoon directed by Tex Avery, but it flips the usual storyline on its head by making Bugs the dupe instead of the sly wisecracker who always gets the upper hand. It also breaks the fourth wall right from the opening credits, using the device to propel the story into motion. Bugs strolls casually in front of the credits and begins reading them out, peering intently at the words and mangling the names of the animators and writers. The joke is that his indignation over the title is what kick-starts the action: furious over the idea that a mere tortoise could ever beat him, Bugs rips the credits to shreds, revealing the forest scene behind them, then tracks down Cecil Turtle and challenges him to a race. The film then gets a lot of mileage out of its reversal of the usual Bugs tale. Instead of Bugs deftly avoiding a pursuer and making a fool out his hapless adversary, he's taken in by the turtle's clever scheme, which involves using all of his turtle friends, strategically placed along the race's path, to make Bugs think that he's always losing. Every once in a while, Bugs passes one of the turtles, is puzzled how Cecil ever got ahead in the first place, and soon comes along yet another of the turtles, who he again thinks is his seemingly sluggish opponent. The turtle even steals Bugs' signature move, planting a big kiss on the rabbit whenever he encounters him.

As much of a kick as it is to see Bugs in a somewhat different role than usual, this is still a middle-of-the-road Warner short, with surprisingly standard animation considering what Avery could do when he really cut loose. During the race, the animation is fairly static, conveying motion and speed primarily by layering blurring effects over Bugs' body and moving the scenery behind him. His body and pose is fairly static from frame to frame, hovering in mid-air with his arms chugging a bit, the backgrounds and speed lines doing most of the work. The result is that, in motion, the race doesn't have the manic intensity that Avery's best cartoons convey.

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is Warner director Robert Clampett at his peak, in a showcase for Daffy Duck that is one of the best representations of this character. Clampett's animation is fluid and wacky, typically relying on wild transitions to give his characters a rubbery, unstable quality that's particularly well-suited to Daffy. In the opening scenes, where Daffy waits anxiously for the mailman to deliver his favorite comic, Dick Tracy, Clampett enlists a staggering array of transformations and exaggerated effects to convey Daffy's enthusiasm and impatience. The duck paces despondently until he sees the mailman coming, at which point he leaps and bounds across the screen like a pogo stick, contorts himself into wild postures, sticks out his tongue and stretches his beak into outrageous angles, his eyes wide and his head shaking in anticipation. He slinks around the back of the mailbox, improbably hiding his entire body behind its slender post while his eyes, bulging and physically directing themselves towards the approaching mailman, sidle out from behind the pole along with the tip of Daffy's beak. This is exciting, visceral animation, expressing the character entirely through the hyperactive contortions that the animation goes through to get across Daffy's outsized emotions.

Once he actually gets his hands on the comic, things get even wilder, as he cheers on the comic detective with the energy of an acrobat, throwing himself into cartwheels through the air, his beak arcing both upwards and downward until its angle nearly reaches 180 degrees. Finally, his celebration of Tracy's victory reaches such proportions that he actually succeeds in knocking himself out with an uppercut to the jaw, sending the duck into dreamland. Clampett occasionally employs motion lines and blurs to achieve his effects, smearing areas of black and yellow across the screen to suggest Daffy's motion, but more often his animation hinges on the prodigious stretching and morphing that he enacts on the character. In individual frames, Daffy's body is often twisted into odd shapes, so that in motion the overall flow has that distinctive rubbery style. The rest of the short doesn't have anything quite as dazzling as the opening minutes centered on Daffy, but the duck's fantasy of himself as the private eye Duck Twacy is amusing, especially when it opens with a shadowy outline of the duck dick which, just for a fleeting moment, takes on the famous profile of the funny page cop that Clampett is paying tribute to.

The short even borrows Tracy's famous rogue's gallery, with visual references to Flattop and other Tracy villains, with even the cartoon's original gangsters obviously modeled off the precedent set by cartoonist Chester Gould's grotesque creations. There's something curiously stiff about these appropriations, though, and they're awkwardly integrated with the riotous energy of Daffy. The Tracy villains barely move at all, and some of them are just completely static drawings, no more active than the backgrounds. They nicely capture the gothic atmosphere of the Gould comics, but as animation most of this segment just doesn't work at all, pitting as it does the absurdly frantic Daffy against what appears to be an army of cardboard cutouts. The short feels incomplete as a consequence, but it's still a miniature masterpiece if only for being the definitive presentation of Daffy Duck as a lunatic perpetual motion machine.

Despite its title, Frank Tashlin's The Case of the Stuttering Pig is mainly notable for its villain, a dastardly lawyer who ingests a Jekyll and Hyde potion in order to wrest an inherited estate away from young Porky Pig, Petunia Pig, and their assortment of more generic relations. Porky's the titular star, but other than his trademark stutter he doesn't have much of a character, and his main job here is to act scared and creep around an atmospherically lit old house. Tashlin does an excellent job of establishing an eerie mood, inspired by classic horror fiction to such a great degree that when, in the opening scenes, a knock at the door on a stormy night inspires fear in the pigs inside, one almost expects Poe's raven to be on the other side. He makes great use of negative images in order to convey the shifting of light and shadow brought on by lightning strikes, alternating the areas of black, white, and grey in the exterior shots of a hilltop mansion. It's a simple but expressive effect.

The film moves along at a brisk pace after the atmospheric opening, focusing mainly on the lawyer as he transforms himself into a Hyde-inspired monster, with an elongated black nose, a bulky torso, and tremendous teeth that are constantly exposed in a fiendish grin. Tashlin gets the maximum impact from the transformation by stretching it out, as the lawyer drinks the potion once with no effect, straining to change and then mixing up a second, more potent glass that does the trick. The scene is filmed from straight on, so that as the transformation is completed the monster begins to take up more and more of the frame, leaning forward until the whole frame is filled with his horrifying face, his teeth bared as though he's about to devour the audience — a threat made explicit when the monster's rant about his pending piggy victims soon spills over to take in the movie theater audience as well, pointing out a guy in the third row who especially annoys him for some reason. The monster eventually figures out that breaking the fourth wall can go both ways, with a neat ending gag that saves the piggies and delivers the villain's comeuppance. But before this, Tashlin gets the most out of his monster, accentuating its strangely graceful walk, with its skinny legs supporting a tremendous body, its evil grin and black-rimmed eyes. This is classic horror performed with cartoon pigs, and oddly enough no less creepy for it.

5 comments:

I've been getting into Tex Avery recently and while reading about him online, I discovered an anecdote which relates directly to the first cartoon you describe. In fact, that ending which you felt was rather lame precipitated Avery's departure from Warner Bros.: his original gag had the duo going off the cliff not two but three times and then on the third time, turning to the audience to say, "Hold onto your hats, folks, here we go again!" which was apparently the punchline to a scatological joke popular at the time. The studio thought this went to far and redid the ending behind his back. Infuriated, he left Termite Terrace for good.

Or so my source indicated. (To pull a Scooter Libby, my source was wikipedia. Take that for what you will.)

For some reason, I much prefer the 40s Looney Tunes. Something more unhinged about them, plus the animation is often richer than that spare 50s style. And I prefer Daffy as an almost frighteningly deranged manic personality than as the irritable, short-tempered fowl he became.

Hey MovieMan. Yeah, after I posted this I was reading up on that cartoon, and came across the story about Avery's departure. That makes sense, the ending as it is now has the feeling of a cobbled-together cop-out of some kind, I just didn't realize it was the studio stepping in to censor the original, which sounds much funnier.

I'd agree with you that there seems to be something special about the late 30s and early 40s Looney Tunes, but I haven't watched nearly enough of them (at least not since I was a kid) to make any general pronouncements. Part of what I don't like about the otherwise great Golden Collections is how difficult it is to get some idea of chronological or artistic trends within the 'toons.

Hello Ed. I'm no great fan of this kind of thing but you write so lucidly that it was fascinating to read.

I've been doing a few reviews of animated films recently entitled 'Animation Month'.

I was wondering if I could link to this piece or maybe one of your Svankmajer reviews as part of a post of links shining greater light onto the animated media.

Thanks, Stephen

Hey Stephen, thanks for stopping by. Of course you're free to link to this post and any other animation-oriented ones you like here. I really appreciate it, and now I'll have to go check out your Animation Month; sounds great!

Thanks Ed.

Post a Comment