Adapted from one of David Mamet's plays by Mamet himself, Glengarry Glen Ross is severely constrained by the stagebound nature of its material, giving it a claustrophobic, airless quality that director James Foley does nothing to mitigate. The story of a group of real estate salesmen struggling to meet rigid sales goals with the threat of losing their jobs dangling over their heads, the script mainly consists of a set of repetitious, utterly circular conversations in which these angry, frustrated men rant and rave, spewing vulgarity and saying the same things over and over again. Their leads are no good. They can't close these leads. The leads are shit. The leads are fucking shit. The boss is a no-good cocksucker. They curse a lot: a lot. Mamet seems to think that realism means having his characters say "fuck" every other word and constantly repeat themselves, but the result is merely strained and, very quickly, exhausting. It doesn't help that Foley has only the most pedestrian solutions for directing most of these conversations. In a movie that consists of virtually nothing but one long, heavily stylized conversation or monologue after another, it is absolute cinematic torture when the director can think of nothing better to do than to cut, on the dialogue, back and forth from one closeup to another, occasionally varying things with a two-shot. In some of the more quickly paced conversations, it even becomes unintentionally kind of funny, as Foley cuts back and forth between actors exchanging quick words or bits of words, the syncopated rhythms of the editing completely disrupting the sense that the actors are even in the same room with one another, let alone sitting at the same table. It's maddeningly distracting.

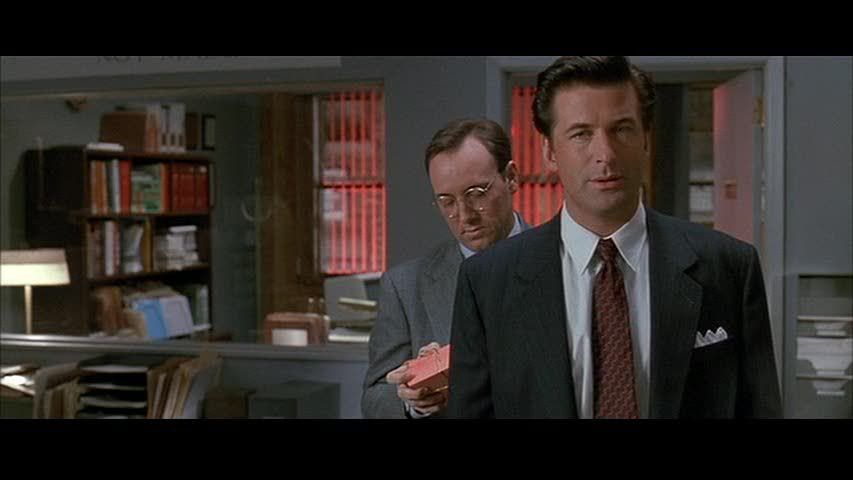

The film's basic idea certainly has some promise to it. A bunch of down-and-out salesmen are working on squeezing the last bits of life out of their mostly dead prospects. The best of them is Ricky Roma (Al Pacino), who's on a streak of luck. Meanwhile, neither the stuttery, awkward George (Alan Arkin) nor slick old-timer Shelley (Jack Lemmon) have done much of anything lately, and even the cocksure, abrasive Moss (Ed Harris) is struggling. They're all overseen by the smug, rigid office manager Williamson (Kevin Spacey), and they're given some fiery "motivation" by a representative of the uptown head office, the priggish Blake (Alec Baldwin), who gives the salesmen an ultimatum: make the top two slots this month or get out. There's some high-powered acting talent on display here, even if this stellar cast isn't given much to do besides bluster endlessly. The script has so much spit and venom that none of these great actors are really able to add much depth or nuance to their one-dimensional characters, with one very notable exception.

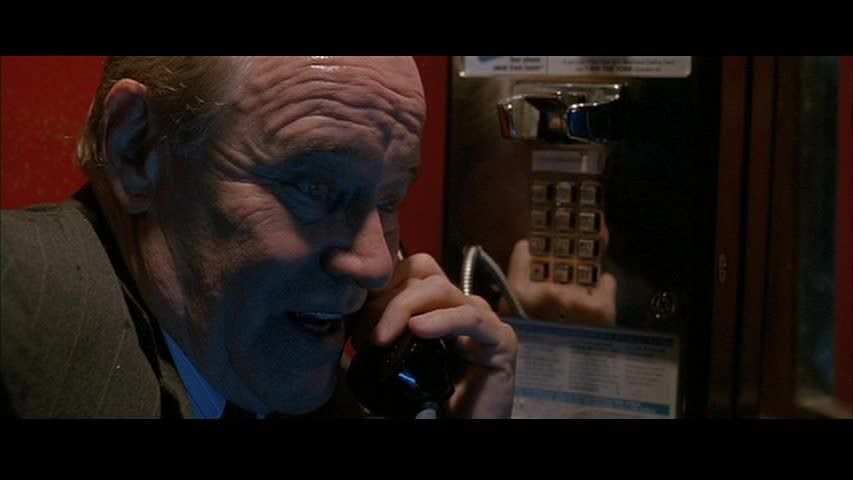

In a film mostly populated by soulless caricatures with no substance, Jack Lemmon's Shelley shines as the one decent, truly fleshed-out portrayal of the bunch. Other than Arkin's non-entity wallflower, Lemmon's is the only performance that consists of more than cursing at the top of his lungs. He takes the script's vulgarity and broad strokes and makes them his own, really sinking into this character, living it, writing it in the lines of his face and the earnest, pleading quality in his voice. There's more than a little Willy Loman in his over-the-hill salesman, still ready with lots of fast talk and slick double-dealing, but no longer having the numbers to back up his skill. He insists he's just hit a streak of bad luck, but nobody cares, focusing only on what he's done lately. Lemmon brings his quiet dignity and reserve to the film, adding much needed subtlety to a script that is otherwise inclined to use bigger and bigger hammers to hit its tiny nails. The film's apparent messages — about the uselessness of a life dedicated only to a soulless job — are most forcefully felt in the character of Shelley.

Foley also reserves his most potent directorial flourish for Shelley's pivotal moment, after he finally succeeds on an important sales call and is describing his victory to Roma. As Shelley describes his sale in hushed, quasi-spiritual tones, the camera drifts airily backward, forsaking the back-and-forth cutting on dialogue to take in the whole scene in the office, with a low angle shot that increasingly isolates the two salesmen in the center of this big empty space. It's a shame that Foley isn't able to expand upon the material like this more often. It's a lovely shot, commenting on the emptiness of Shelley's victory even as it captures his very real enthusiasm and nearly ecstatic joy. Elsewhere, the exterior shots, bathed in neon colors and pouring rain, are evocative but don't really add up to anything. And Foley's simplistic way of dealing with the vast majority of the dialogue scenes drags the life out of them, even if there are still some sparks in the best patches of Mamet's dialogue. There's a truly great sequence in which Roma delivers a lengthy, rambling monologue about absolutist morality, attitude, religion, and the importance of personal choice. It is a speech of astonishing amorality, and the scene's payoff comes when Roma climaxes this dazzling oration by whipping out a sales brochure and spreading it out on the table in front of his slack-jawed companion: all this eloquence and ranting for the sake of selling a parcel of Florida real estate.

At its best moments, like this, the film has the capacity to surprise with its dark wit and harsh insights; its mordant satire has some real sharp teeth. But its rambling structure, functional style and repetitive dialogue diminish the material's potential. Large chunks of the film are dedicated to hammering home the same points repeatedly, particularly anything involving Harris or Arkin, who play the same note throughout as though they're incapable of hitting any other. The scenes where the two of them are talking together are thus doubly exhausting, especially since they converse at length throughout the whole first half of the film. There's the foundation of an interesting film here somewhere, but the film that actually got made isn't it. Despite flashes of quality, and even sporadic brilliance, Glengarry Glen Ross is mostly monotonous and cinematically limited.

5 comments:

"... this stellar cast isn't given much to do besides bluster endlessly ..."

"... Large chunks of the film are dedicated to hammering home the same points repeatedly ..."

"... is mostly monotonous and cinematically limited ..."

Amen. I only got around to watching this film within the last year, and I was stunned at just how limited it is. By the halfway point, it's really said about everything it has to say, and then it spends the next hour saying it again.

The thing that really irks me though is the habit of having characters ramble endlessly one scene and not say a word the next, depending on if they're supposed to be the blusterer or the listener. I think that's the biggest element of why it feels so staged. It's like a series of monologues rather than dialogues.

"Glengarry Glen Ross is severely constrained by the stagebound nature of its material, giving it a claustrophobic, airless quality that director James Foley does nothing to mitigate."

Well, that's kinda the point, isn't it? These guys operate in a hermetically sealed world that is closing in on them because of the threat of being fired. I think that Foley did a great job conveying this feeling in an atmospheric way that did not distract from the performances. I also think that he managed to make it all look very cinematic with the film noir vibe of the night-time scenes -- the oppressive rain and that great shot of the elevated train passing by.

"the script mainly consists of a set of repetitious, utterly circular conversations in which these angry, frustrated men rant and rave, spewing vulgarity and saying the same things over and over again."

You have to ask yourself why is that? What is Mamet trying to say? To me, the point he is making is that these guys who are trying to sell property to people hate their jobs. They get nothing but abuse from their bosses and have to fight tooth and nail with each other in order to not get fired. If you listen closely, there is rhythm to Mamet's dialogue and the actors nailed it perfectly.

"It doesn't help that Foley has only the most pedestrian solutions for directing most of these conversations. In a movie that consists of virtually nothing but one long, heavily stylized conversation or monologue after another, it is absolute cinematic torture when the director can think of nothing better to do than to cut, on the dialogue, back and forth from one closeup to another, occasionally varying things with a two-shot."

What would you have him do? With dialogue that good and a cast that great, the worst thing you could is over-direct a scene or go with some fancy camerawork/angles that would only distract from what is being said. Instead, Foley just lets the actors do their thing which I found absolutely riveting. And, the editing rhythm of the dialogue-heavy scenes, seems to me, be in rhythm with how the dialogue is being said.

"Elsewhere, the exterior shots, bathed in neon colors and pouring rain, are evocative but don't really add up to anything."

Well, they are there to add atmosphere and to give us little breaks between marathon sessions of dialogue. I also think that certainly lighting effects, like bathing the actors in red in one scene symbolizes the hellish predicament they are in. Foley does a fine job as far as I'm concerned. Aside from AT CLOSE RANGE and CONFIDENCE, he's done pretty unremarkable work and this is definitely his best effort to date.

What I like about GLENGARRY is how it is searing indictment of salesman, showing how brutal the daily grind is for these guys, the cutthroat nature of it, and what these guys do to each in order to survive. There is a palpable desperation as epitomized by Jack Lemmon's character to what they do. And then, on the other end of the spectrum you've got the super slick salesman as represented by Al Pacino's character who will do and say anything to land a commission.

I disagree that the film feels like a series of monologues rather than dialogues -- that certainly isn't evident in the scenes between Ed Harris and Alan Arkin who banter back and forth or near the end with Pacino and Jonathan Pryce or even the scenes between Lemmon and Kevin Spacey. I think that monologues tend to stand out because they are so impressively written and performed as epitomized by the famous cameo by Alec Baldwin who really nails his speech.

I'll agree that some of the dialogues are dealt with poorly by the back-and-forth editing, and at times uncoordinated direction, but I certainly like the film a whole lot more than you did.

I think your approaching it from the wrong angle when you note that, "Mamet seems to think that realism means having his characters say "fuck" every other word and constantly repeat themselves," in that I don't believe what Mamet is striving for is realism. In fact, I think the dialogue in this film is exemplary among his other works. The reason being that Mamet is less like a Smith or a Tarentino who use their cursing like punctuation in order to fill out their exposition, and is more like a Chayefsky (stylistically, not substantially) in that he uses cursing as well as overlapping dialogue and repetition to craft a stylistic approach, his writing doesn't represent the reality of the sales room, but what's behind the reality. A hollow, empty, repetitive existence that is rendered utterly superfluous, and he illustrates this through his stylistic flourishes. But that's just me.

"Mamet seems to think that realism means having his characters say "fuck" every other word and constantly repeat themselves,"

To Joshua's point, it seems as if you're not too familiar with Mamet's body of work. The statement quoted above is usually made by those that haven't really seen his plays.

Tony, you're right that I'm not familiar with Mamet's work -- I can only respond to what's onscreen in this film, and to me the dialogue quickly became monotonous and circular. This techique can be effective -- Joshua mentioned Tarantino and I think he often does it well -- but here there was just no variation in the repetitious dialogue. I really don't get why so many people praise the writing in this film. I also don't see much of a fundamental difference in the way Mamet uses cursing here versus the way Tarantino does; except that the latter's dialogue, even at its worst, seldom strikes me as limited as this. I might very well enjoy other Mamet films (or his plays), but this one is so one-note, in both its themes and its language. There are so many scenes that just repeat the same idea over and over again. I wanted to scream at the screen: we get it, move on.

Post a Comment