Otto Preminger's weird, disjointed Whirlpool is an intriguing mess of a film, part film noir, part psychological case study, an unflinching examination of marriage, fidelity and the ways in which rigid ideas about gender and propriety can cripple and deform relationships. Ann (Gene Tierney) is seemingly a model wife to her psychiatrist husband Bill Sutton (Richard Conte). She's pretty, loving and devoted, and he's proud to be married to her — and even prouder, he tells her, when he sees how people gape at her at parties, awed by her beauty and envious of him for being her husband. For her part, she feels grateful just to have him, and is sorry that she can't do more for him. She regrets that she isn't intelligent enough to have a conversation with him about his work, and he just pats her paternally on the head and tells her he wouldn't change a thing about her — a condescending gesture that's also sort of an insult, an acknowledgment that he agrees she isn't on his level intellectually. Their marriage, so admirable and loving on its surface, is warped by an inability to communicate, by Ann's desperate desire to maintain this illusion. Beneath her façade, she's miserable. Feeling constrained and hemmed in, she asserts her freedom through acts of kleptomania, shoplifting even though she and her husband have more than enough money to buy almost anything she could want.

Unfortunately, Ann's shoplifting brings her to the attention of the disreputable hypnotist and con artist David Korvo (José Ferrer), who uses her weakness to gain control of her, worming his way into her life. Ann believes she's sick, but unwilling to go to her husband and shatter his perfect image of her, she turns to Korvo to cure her of her kleptomaniac outbursts, her headaches, her insomnia. Tierney plays Ann like a blank slate, a vacant Barbie doll just waiting to have her head filled with anyone else's ideas. Even before Korvo begins hypnotizing and manipulating her, she is in a sleepwalking daze, her pretty face as inexpressive and blank as a doll's, her eyes staring off vaguely into the distance. She seems completely devoid of substance or vitality, her every movement and facial expression carefully studied and deliberate, her face a mask. She is crafted from something hard and cold and inanimate, anything but flesh.

This is a strikingly cynical portrait of the "happy" marriage: the husband mainly concerned with how jealous other men are of him, the wife trying her best to maintain the public image of their ideal union. This fragile situation makes it very easy for the sinister Korvo to use Ann towards his own ends, namely to dispose of his troublesome former lover Theresa (Barbara O'Neil), who has been threatening to expose his crimes. His complicated plot to frame Ann for Theresa's murder is where the film begins to fall apart, where the threads of the screenplay start to fray. The whole thing is so obviously ridiculous, so convoluted and yet transparent, that it requires a prodigious ability to suspend disbelief just to go along with it on even the most superficial of levels. Korvo's a fine villain, slippery and slimy, and Ferrer's performance is appropriately despicable. He slithers into Ann's life, insinuating himself into a position of power over her with his sinister grin and thin, rodent-like face.

This makes it doubly unfortunate that the film wastes such a good villain on such a shaky plot. For a guy who's supposed to be a clever manipulator, it's bizarre that his scheme includes planting crucial evidence against himself at the crime scene, hypnotizing Ann into hiding it when he could have just as easily made her destroy it. By the same token, his alibi for the murder — a gall bladder surgery — seems clever when one suspects that he's faking it, or that he's hypnotized a doctor into giving false evidence. It becomes less clever once one realizes that Korvo actually subjected himself to a genuine operation, and that his brilliant scheme requires him to hypnotize himself into not feeling pain, so that he can sneak out of the hospital to perform his nefarious deeds. The script is a mess, one of those absurd Hollywood concoctions that provides only the barest of rational explanations for its twisted narrative. Even at the finale, it's by no means clear that Ann has actually been cleared of Korvo's crimes, but the kindly police inspector acts as though everything's been resolved and she's free to go. By that point, so much other ludicrous business has been required by the plot that this seems like a relatively minor logical hole.

The fractured, often nonsensical plot is a large hurdle to get over in enjoying this film, but Preminger's typically calm, assured direction smooths out some of the more egregious wrinkles. His darting, swooping camera helps define the relationships between the characters, as in the scene where Ann is first hypnotized by Korvo, and the camera makes a slow rightward move, a short arc that ends with a perspective looking past Korvo's shoulder and slightly down at the staring, distant Ann. The camera calls attention to what's happening, to Korvo assuming a dominant position over Ann, looming above her as he takes control of her. In a later scene, Preminger signals Korvo's tightening grip on Ann by literally tightening the shot, slowly inching the camera in until the two are packed closely together within a constrictive frame, their intimacy forced not only by Korvo's shady maneuvers but by the borders of the image itself. Preminger's formalist sensibility continually asserts itself, his purposeful blocking delineating the ideas and relationships within the film even as its script collapses into incoherence.

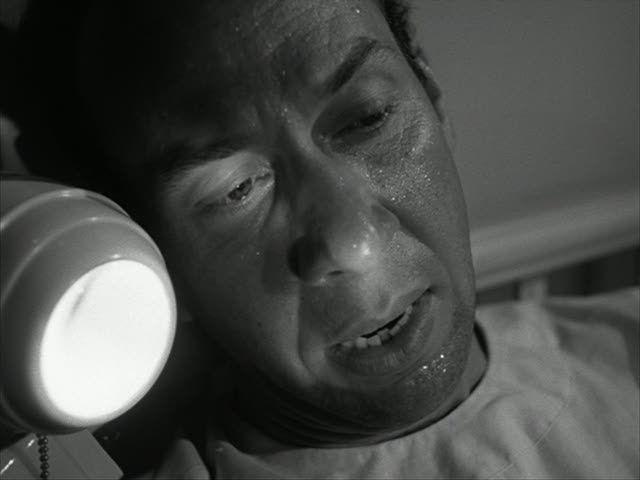

He's at his best in visualizing that which goes unstated, the emotional underpinnings of the story lingering beneath the surface. This tortured script doesn't actually leave much unsaid, but Preminger's subtle sensibility is still present. There's a wonderful short scene in which the police lieutenant (Charles Bickford) wakes up in the middle of the night, unable to sleep from thinking about the case. It's a simple scene — the lieutenant just calls his precinct and gives out an order — that for another director would be a practical formality, a quick, necessary transition. Preminger sees more in it, sees the policeman's grief over his dead wife and the direction in which his sadness might lead his thoughts. Preminger carefully frames the shot to accentuate the photo of the wife in the background, her presence just behind the policeman calling up the unspoken undercurrents of his decision to allow Ann and Bill a chance to prove her innocence and redeem their marriage.

All the same, this is undoubtedly minor Preminger, one of the weakest films of his stint at Fox. The film starts with an interesting premise, and it's fascinating to watch Ferrer's sinister Korvo interacting with Tierney's blank-faced portrayal of a blank non-entity. The ending's confused jumble is weirdly compelling partly because Ann doesn't actually seem to have changed much: she has the same blank stare, the same zombie-like intonation, when she's coming out of her trance as when she went into it. This injects an element of uneasiness into the ending's supposed marital reconciliation, suggesting that the only changes are on the surface, while the deeper problems remain. The film is a failure as a whole, but its disarmingly frank subtextual commentary on marriage and appearances, along with Preminger's crisp visual treatment of the material, makes it at least worth a look.

2 comments:

I never saw this film, but as it's a Preminger, I understand it does need to be negotiated. So basically you are saying here that Preminger's ability at visualizing what goes unstated manages to at least partially mitigate the weak script. But you also admit later that it's one of the weaker Premingers.

Pauline Kael refers to it as a "stinker" and says that "the scriptwriters, Ben Hecht (hiding in shame under the pseudonym Lester Barstow) and Andrew Solt, must have really had it in for the director, Otto Preminger.

LOL!

It's undoubtedly minor Preminger, and the script is a true mess. But it's Preminger, so there are at least interesting images and ideas here and there. Worth seeing if you're a Preminger completist, otherwise easily skippable.

Post a Comment