[This post is prompted by The Oldest Established Really Important Film Club, which will be spotlighting a different blogger-selected film every month. This month's selection is courtesy of Pat Piper from Lazy Eye Theatre. Visit his site to see his thoughts on the film and to join the main discussion.]

[This post is prompted by The Oldest Established Really Important Film Club, which will be spotlighting a different blogger-selected film every month. This month's selection is courtesy of Pat Piper from Lazy Eye Theatre. Visit his site to see his thoughts on the film and to join the main discussion.]

Lindsay Anderson's

If.... is a harsh, uncompromising nightmare vision of British society as a culture unhealthily obsessed with tradition, locked into brutal, nearly fascist rituals and a blind, cowering respect for authority. Set in a British boys' college where the discipline is draconian and completely without rationale, the film examines the peculiar pressures placed on young men in a society where militaristic virtues such as loyalty, obedience, servitude and conformity are held up as the example. This school establishes a rigorous chain of command, selecting the most obedient of the older boys as "whips," who then become disciplinarians, keeping the younger boys under control. The result is that the school seems structured not so much for real education as for indoctrination and control — the only thing these boys are learning is that, in order to get by, they must learn the rules by rote, parrot back what they're told, never question orders, never think for themselves. Anderson juggles multiple storylines throughout the first half of the film, showing the way the school is run from multiple perspectives.

Jute (Sean Bury) is a new boy in the school, and he provides the newcomer's perspective in the early scenes, looking at the chaos around him with wide, terrified eyes. He is quickly taken under the wing of another boy, who impresses upon him the importance of obedience, of learning the rules quickly and being able to pass the complicated tests that will be imposed upon him. Jute is the film's icon of innocence, a usually silent and cherubic witness to the horrors around him, confused and disheartened by what he sees, unwilling to be shaped into the cold, brutal thing that this place seems design to churn out. There are other boys drifting around the film's edges, too, mostly stock types like a scrawny loser who's constantly being beaten up, a fat kid, and a quiet intellectual who generally buries himself in his telescope or his studies. But the film quickly centers itself around the school's trio of rebellious outcasts, the three friends who refuse to conform, who refuse to bow politely before the pointless discipline and cruelty of this place. Mick (Malcolm McDowell) is the de facto leader of the trio, with Johnny (David Wood) as his best friend and co-conspirator, and Wallace (Richard Warwick) as their somewhat slow-witted, dopey buddy. These three boys have the only reasonable reaction to the absurd regulations of power-hungry whips like Rowntree (Robert Swann) and Denson (Hugh Thomas).

Anderson presents this college as a nasty, suffocating place, piling on one infuriating incident after another until it seems obvious that

something has to break, that no one could sustain this much tension and pressure. There is more than a hint of the absurd here, too. The whips are fey and masochistic, fingering their canes as though they'd really love to use them at any moment. They shout at the students to stop talking even before anyone has talked, as though always anticipating some minor infraction over which they can exercise their power. They survey their fellow students in the lower levels like military drill inspectors, advising them to cut their hair, making sure they're docile and ready for bed at the proper time, and capriciously confiscating any trivial item they deem unnecessary. The teachers are no better. The headmaster (Peter Jeffrey) is a pompous elitist who seems to fancy himself an education reformer, adapting to new times, when in fact his school is run like a barbaric Middle Ages prison. He leads the whips around the grounds at one point, boldly orating about the necessity to encourage creativity in young minds, to enlighten the next generation, to prepare them for life. His words are hypocritical, of course, considering his audience — the brutish thugs whose job it is to beat and suppress the younger students — and his spiel about education is especially empty when contrasted against the scenes in actual classrooms.

The teachers, for the most part, barely engage with their students. A professor of mathematics marches around the room intoning abstract phrases about geometry, lessons that can have no real meaning without demonstrations and diagrams, and yet he randomly stops every so often to ask a student if he understands. Then, even if the poor boy says yes, he slaps him in the head, or molests him in some way, at one point worming his hand inside a boy's shirt to caress his chest. Anderson's style is exaggerated and absurd, presenting these shocking, over-the-top images side by side with more naturalistic and conventional presentations of college life, the brutality and oppression of students guided by pointless rules. The result is metaphorical more than realistic: Anderson views education as a process of molesting and deadening the minds of the young, so he presents the education system in his film as

literally abusing and violating the children it's supposed to be teaching. Only one teacher here even tries to engage his students, talking about the power of fascism and asking the students if they believe that fascism arises because of one powerful, evil leader, or because of a whole society of docile, casually evil people. As if to prove his point, the students simply stare back at him, uncomprehending.

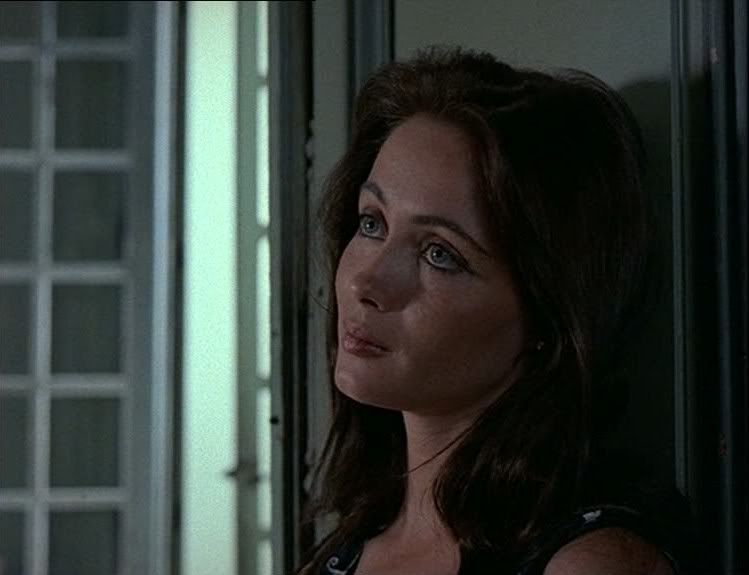

This question is a central theme of the film, particularly in its final acts. The film slowly slips more and more into an absurd, surrealistic dreamworld in its second half, particularly after Mick and Johnny go out on a trip to town. The two boys steal a motorcycle, riding through the lush, open green fields of the countryside, laughing as the speed blurs their faces; it's a potent image of freedom in a film where these boys are hemmed in on all sides by oppression and a denial of free will. At an empty offroad café, the two boys meet a young girl (Christine Noonan), a waitress who will turn out to be a pivotal and mysterious presence, gently nudging the film into the spiraling surrealism of its denouement. At first, her confrontation with Mick and Johnny is utterly prosaic and nearly silent, as the boys snarlingly order coffee and Mick tries to grab her for a kiss, getting violently slapped for his efforts. But then the tenor of the scene abruptly changes, as the girl begins seducing Mick; they act like tigers, snarling and clawing at one another, rolling around on the floor tearing at their clothes, until suddenly their clothes disappear altogether and the girl is biting Mick's arm. The whole interlude is over as suddenly and inexplicably as it began: a lurid and transitory dream vision of animalistic sexual release. It's a true down-the-rabbit-hole moment, signaling the film's increasing departure from reality into a netherworld of dreams and nightmares.

The girl, who periodically reappears without explanation as an icon of freedom and sensuality for the three rebel boys, leads them into the final act of the film, in which the school is taken over by militaristic fervor. Generals and bishops visit, along with distinguished men and women dressed up for some pomp and circumstance, while the students, now dressed as soldiers, march around in formation, chanting and playing tightly controlled war games with paintball guns and firecrackers. This, Anderson suggests, is what this kind of oppressive conformity is grooming people for: to be soldier-automatons, ready to die for God and country, always willing to obey, never questioning orders. Only Mick, Johnny and Wallace really stand out, refusing to go along with this absurdity: while they lounge around in exhaustion, bored with this ritualistic violence, other students teach each other the "scream of hatred" that's yelled out when charging one's enemies. Then, just as these war games are starting to die down, the three boys begin shooting real bullets at the administrators and teachers, finally shooting and then bayoneting a priest in a general's garb. Absurdly, the boys are given a slap on the wrist for this offense, and asked to apologize to the dead man's corpse, which is kept in a wooden drawer in the headmaster's office and sits up to shake their hands before lying back down, playing dead. Obviously, the film has departed from reality by this point, increasingly existing in a fragmented fantasy in which these boys are finally able to strike back at their oppressors, using the headmaster's much-vaunted creativity and imagination to fashion an alternative world, one in which they're actually free.

The paradox, of course, is that having been themselves created by an atmosphere of cruelty and violence, the only freedom they can imagine is the freedom to wage war. The film's final scenes are a horrific vision of anarchy and destruction in which the rebels and the authorities (the latter represented, cartoonishly, by stereotyped authority figures like generals and bishops, as well as a knight in armor) go to war, everyone handling submachine guns as though they were born to. This anarchic finale suggests burning everything down to start anew, but Anderson's vision is more nuanced than Mick's punk rage. There's a moment earlier in the film that suggests a more utopian possibility for change, when Wallace's graceful exercises on a high bar halt a gym class, as the younger students, including the gay Phillips (Rupert Webster), stare at him in awe and admiration. The scene is staged in languid slow motion, as the younger students watch the fluid movements of the older boy as he spins around the bar, his body curling up and unfurling like a jackknife. There's a sense of wonder in this scene, a sense of real connection, that presents an alternative to the violence, hatred and disconnection that's everywhere else in this film.

This scene, like many others dotted throughout the film, including the café scene, is shot in black and white, which Anderson randomly intersperses with the color footage, creating disjunctions that call attention to the film's essential unreality. This approach separates Anderson's

If.... from its obvious black and white influences,

Zero For Conduct and

The 400 Blows, the seminal French films of youthful rebellion and authoritarian oppression. Anderson nods to those films, but tweaks their verité aesthetics by often setting his most disjunctive and surrealist scenes in black and white, reversing the usual conventions about black and white stock versus color. Elsewhere, during a church service that's shot in black and white, Mick looks up briefly and sees a stained glass window in dazzling, brilliant color, a sudden vision of spirituality and clarity to offset the numbing banality of this college. This is a startling, utterly original film, a potent and unrestrained critique of a society seemingly teetering on the brink of fascism. Anderson is spitting in the face of the establishment, crafting a film as rebellious and revolutionary as his proto-punk protagonists.