[This is a contribution to the Boris Karloff Blogathon, which has taken place from November 23-29 at the Frankensteinia blog.]

The Mask of Fu Manchu is, it has to be said, an utterly bizarre movie in so many ways. This quickie shocker casts Boris Karloff as the titular Fu Manchu, a sinister Chinese scientist and criminal who's determined to find the sword and mask of Genghis Khan in order to secure his own power as a new world conquerer. In order to do so, he kidnaps the professor Lionel Barton (Lawrence Grant), who's about to lead an expedition to the newly discovered tomb of Khan. When this doesn't work, Fu Manchu sends out inept assassins, kidnaps more scientists and adventurers, concocts elaborate torture devices involving pits of crocodiles and spiked walls, and plots in his laboratory with his slinky, oversexed daughter Fah Lo See (Myrna Loy). The plot is so over-the-top it's not worth taking seriously, so it's fortunate that the film, directed by Charles Brabin (replacing Charles Vidor, who was fired after a few days), offers up plenty of outrageous images and outlandish moments to distract from its ludicrous narrative.

The film's whole construction is rough and even sloppy. Everything seems to be happening at an accelerated pace, as though the actors were instructed to get through every scene as quickly as possible. This is often frankly hilarious, as the actors spit out lines, sometimes stumbling and stuttering — mistakes that obviously no one thought were worth doing another take to correct — or scrambling to perform some physical task at triple speed. The film was made early in the talkie era, and this too shows in the roughshod aesthetic. Brabin films mostly in static tableaux from a distance, occasionally tracking into or out of the scene but mostly just setting up and letting the action play out in front of the camera.

What happens in front of Brabin's camera, mostly, is Karloff and Loy outrageously mugging as the sinister Chinese villains, while the ineffectual heroes — led by Barton's daughter Sheila (Karen Morley, shamelessly overacting even in comparison to the makeup-caked Karloff and Loy) and her whitebread boyfriend Terry (Charles Starrett) — stumble into their enemies' traps over and over again. Karloff, even covered in ridiculous slant-eyed makeup, is in fine form, making his Fu Manchu snakelike and strangely dignified, insisting on being called "doctor" and stressing his fancy American/British education even as he vows to destroy white culture. Loy, as his daughter, is equally entertaining to watch; Fah Lo See is a seductress who turns her attentions to Terry almost as soon as she sees him. Fu Manchu is very aware of his daughter's ways, too, first offering her as a payment to Barton (with the girl standing right there) and then telling her to hold off on her usual seduction routine until her latest target has outlasted his usefulness to Fu Manchu's plans. Indeed, the film is surprisingly open and explicit in its sexual and other undertones. At one point, trying to find Fu Manchu, the adventurer Nayland Smith (Lewis Stone) asks an innkeeper for some "rest," and the obvious implication is that he wants either opium or women.

As interesting as these surface elements are, the film's strange undercurrents of homoerotic imagery and exoticization are even more fascinating. Once Terry is taken prisoner by Fu Manchu and Fah Lo See, he's stripped to the waist and chained to a slab so that Fah Lo See can lounge over him, running her long claw-like fingernails across his chest. And then there's the scene where Fu Manchu does the same thing, running his own nails across Terry's chest, mirroring his daughter's admiration of this white man. At one point, she even implicitly offers up Terry for her father's appreciation: "He is not entirely unhandsome, is he, my father?" To which Fu Manchu responds, "For a white man, no." This homoerotic undercurrent certainly extends to the black servants who are kept by the Chinese: strapping, muscular dark men, half-naked in tiny underwear-like shorts. They stand around looking like statues with their sculpted bodies, and it's hard to look at them without thinking that Fah Lo See, and probably Fu Manchu as well, likes having such models of masculine physicality hanging around.

Of course, beyond these under-the-surface sexual implications, there's the obvious fact that the film posits a fantasy world where Chinese warlords have black slaves: it's an expression of white fears about non-white races joining up to overthrow the whites. The film is shockingly racist, and not just the run-of-the-mill racism one expects of a 1930s film with stock Chinese villains. It's not just that the Chinese speak with affected accents or that the two most prominent Asian characters are played by white actors in slant-eye makeup. No, Fu Manchu's sinister plot is explicitly framed as a racial conquest, as an attempt by the sneaky, evil "yellow" people to conquer the white races. And not just conquer them, either. Fu Manchu extols his Chinese warriors into battle by promising that they will be able to kill all the white men and steal their women. Fu Manchu's goal is thus couched in terms of non-white races defiling white female sexuality, a tradition that stretches back at least to Birth of a Nation and is often at the core of racist thinking. Racist ideologies excite fear by suggesting that white female sexuality — represented here by willowy blonde Karen Morley, who looks frail and vulnerable despite her shallow tough attitude — is in danger of being corrupted and destroyed. The Mask of Fu Manchu goes even further by placing male sexuality in danger too, as Terry nearly gives in to the wiles of Fah Lo See. Of course, in one of the film's more laughable scenes — and there's some tight competition for that title — Sheila wins Terry back to white women by melodramatically urging him to put his arms around her and then smugly gloating at Fah Lo See when he wakes out of his trance.

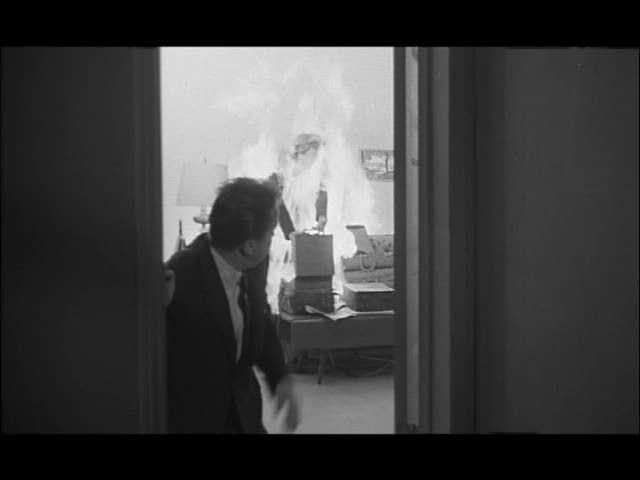

Because of all this drama surrounding race and sexuality, The Mask of Fu Manchu is a fascinating and problematic film, messy and absurd and teeming with wild images. Fu Manchu's introduction is especially iconic, as the mad doctor appears, sneering and mugging, on the right side of the frame while on the left an oval funhouse mirror distorts and stretches his face into a disembodied monstrous mask. Later, when Terry is being whipped by some of the black slaves under Fah Lo See's direction, Fu Manchu's head appears floating in blackness, disembodied again, leering at the spectacle of the white man's torture. Images like this, along with the ornate designs of things like Genghis Khan's forbidding tomb, make the film an interesting spectacle, dominated by lurid imagery, loony ideas and unfettered performances.