Jacques Rozier is one of the unfortunately forgotten filmmakers of the French New Wave. He finished his debut film, the excellent

Adieu Philippine, only with difficulty and some monetary help from his friend Jean-Luc Godard, and afterwards he wouldn't make another feature for over 10 years. His second feature,

Du côté d'Orouët, is, like his debut, a charming and moving depiction of young people on vacation. Ambling and nearly plotless, the film meanders through two and a half hours of beachside antics as three friends — Caroline (Caroline Cartier), Joëlle (Danièle Croisy) and Kareen (Françoise Guégan) — take their September vacation in a seaside cabin owned by Caroline's family. It's a relaxed and simple film, and also a really beautiful one, progressing slowly and organically from carefree goofing around to the rich and subtle emotional complexity that begins to develop later in the film. Rozier is paying tribute to the joys of youth, the pleasures of a month-long escape from the day-to-day mundane slog of work and normal life, but as in

Adieu Philippine there's a subtle undercurrent of melancholy that, as the film goes along, is increasingly laid bare beneath the surface giggling and good times.

This somewhat more serious subtext is first hinted at early in the film, soon after the three girls first arrive at their summer villa. They've been laughing and goofing around nonstop throughout the whole trip, even laughing breathlessly all through a steep climb up a sand dune, lugging their suitcases step by laborious step up its slippery slope. Then they arrive at the house, throwing open its shutters to let in the slightly chilly September sea breeze, and Caroline and Joëlle go running off to look at the rooms upstairs. Kareen walks by herself into a side room, suddenly quiet and introspective: she was childhood friends with Caroline, and the two girls used to spend summers here when they were very young. This is the first time she's been back since then, and a flood of memories come pouring in, bringing her back to her girlhood. Suddenly, Rozier cuts in for a series of probing closeups in which Kareen's face fills the screen, and she looks into the camera and whispers her thoughts about being suddenly overcome by nostalgia, recognizing all these little details from her childhood vacations. It is the only moment in the film when Rozier breaks the fourth wall like this, and the only moment when he so directly and intimately reveals the inner thoughts of these young women. The effect is all the more striking for its status as a solitary stylistic break in the film's aesthetic, a lone moment in which the intensity of emotion necessitates total unguarded honesty and confession. Later, the women will keep their emotions more veiled as they throw themselves into a month of fun and laughter and silliness.

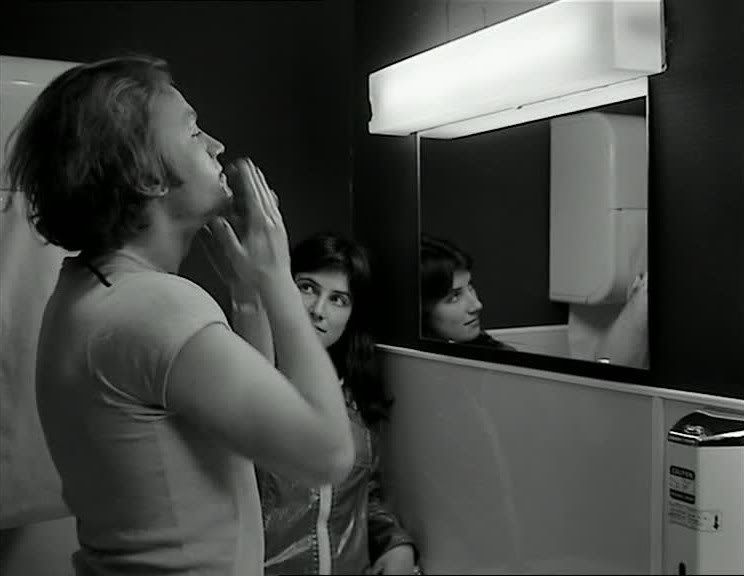

They're joined on this vacation by Joëlle's boss Gilbert (Bernard Menez), who is obviously attracted to Joëlle and surprises them by showing up in the town where they're staying, then tagging along and eventually pitching his tent right in their garden. His presence provides the first hint of fracture within the group, as Joëlle, who's all too aware of his interest in her, doesn't want this tension on her vacation, while the other two girls just delight in tormenting and mocking Gilbert, who at first seems slightly stiff and serious around the giggly girls. Gilbert provides the comic relief initially, as the butt of their jokes — they wake him up one morning by playing cacophonous music on a trumpet and drums right outside his tent, then entangle him in fishing nets — but he becomes a more poignant character later in the film. He hoped to finally form a relationship with Joëlle on this vacation, but instead the girls treat him like a servant, having him fetch things for him while they sunbathe, or leaving the dishes for him to wash while they run off to the beach.

In one sequence towards the end of the film, Gilbert and the girls return from a fishing trip with a big fish, which he prepares for an elaborate meal. Rozier, whose sense of pacing is always unhurried, spends several long minutes with Gilbert as he cooks, swigging wine and looking a little tipsy when Rozier captures him in closeups. He is putting a lot of effort into the meal, juggling large pots on a crowded stove with only two burners, carefully slicing up the fish, preparing vegetables and sauce to go with it. After all this preparation, the meal is received with lackluster indifference, as Caroline and Joëlle, exhausted from a long day of fishing, pick feebly at the food before falling asleep right at the table. Joëlle, additionally, is withdrawn and upset because Kareen has earned the attentions of the sailboat-owning Patrick (Patrick Verde), who Joëlle herself had wanted. Kareen's absence from the table, out on a date with Patrick that's gone way later than they'd expected, hangs over their uncomfortable silence, and at times Joëlle seems on the verge of tears while Gilbert gamely tries to lighten the mood and encourage the girls to eat. Instead, they sleep and the next morning Joëlle, who seems to realize how desperately Gilbert wants her to like him, can barely meet his gaze.

The film acquires a great deal of poignancy by its end, though the shift is mood is subtle and gradual, and doesn't really come until the film is nearly over. Earlier, it's all charming days in the sun, aimless days with nothing to do but chat, argue over what to eat, go on little trips that never lead anywhere. The girls have fun dressing up at home, pretending like they're going to go to a nearby casino they've seen signs for, dancing goofily in wooden clogs. When Gilbert finally does take them to the casino, dressed in a tuxedo and fussing with his bowtie, the casino turns out to be a converted and rather ramshackle farmhouse located in a muddy field. A sailboat expedition with Patrick is more successful, and Rozier spends a great deal of time watching as Caroline and Joëlle hang on through the waves, leaning off the boat to keep it from tipping, laughing and screaming the whole time, while the camera rocks and shakes with the waves.

The film's style is loose and verité, unobtrusive but nonetheless striking. Rozier shot in ragged, grainy color, in the Academy ratio, which gives the film the look of home video vacation footage. Its looseness is appealing, though, and there's an offhanded beauty to many of Rozier's shots. His images, in their unforced beauty, capture the sense of a late-season beachside resort where the vacation traffic is slowing down, most people starting to leave for home just as the girls arrive. It's windy, maybe a little chilly, and the beaches are usually all but empty except for the three girls and a few other stragglers. The season is integral to the film's sadness, a part of the sensation that things are winding down, that this isn't quite the peak, and by the end of the film, as all the local businesses are being shuttered for the winter and the boardwalk is even more desolate than ever, the melancholy becomes almost overwhelming.

This sadness is especially apparent in the character of Joëlle. Rozier never gives her the moment of unguarded confession that he gives to Kareen early in the film, but her sadness slowly shows itself anyway. At one point, after the group has gone horseback-riding and returned home for dinner, Joëlle silently observes as Kareen and Patrick whisper conspiratorially across the table from her, quietly making plans for the next day. Rozier shoots across the table, over the shoulders of Kareen and Patrick, framing Joëlle's face between them as her sad eyes dart back and forth between them. Gilbert praises Kareen's riding skills, and Patrick agrees, saying that she's so light that she almost flies. It's an offhanded remark but Rozier's emphasis on Joëlle captures how much it must sting her; throughout the film, she been very self-conscious about weight and dieting, and the compliment to Kareen feels like a slap to her. All of this plays out very subtly, without anything overt being said. It's simply Rozier's acute concentration on Joëlle's face, his attention to her unspoken emotional state, that makes this little moment and others like it hit so hard.

The film's final half hour uses the end of the summer holiday as a metaphor for the other endings and missed opportunities that underscore this elegiac conclusion. First Gilbert leaves, sick of being treated like "an imbecile," and then Kareen leaves as well, having quickly grown tired of her brief fling with Patrick. Only Caroline and Joëlle remain at the end, sulking through the cold final days of vacation, closing up the house and returning for home and work in a downcast mood. These scenes are gray and overcast; winter is coming, chasing them away from the beach, away from the freedom and irresponsibility of summer. There's a sense of loss in the film's final act that's hard to pin down. Is it that these women are on the verge of having to grow up for good, to leave behind the girlish fun that Kareen remembers from her childhood and which they're recreating here? Is it the sense that soon they'll get married and settle down? Or is it simply that now, as another girl says at the very end of the film, they have to wait 11 months for their next taste of this freedom and adventure, as now they return to the work and routine of the rest of the year? Whatever the case, it's an affecting coda, as the haunted-looking Joëlle watches Gilbert, who has now given up on her, flirt with another girl, talking about vacation plans for next year.

Du côté d'Orouët is a sweet and ultimately sad movie that builds a great deal of emotional richness from what initially seems rather simple. The sadness in the film is not as explicit or as specifically defined as Rozier's first film,

Adieu Philippine (in which a vacationing young man was poised on the brink of military service in the Algerian War) but there's nevertheless a sense that Rozier sees the summer holiday as an opportunity to examine, simultaneously, the joys and the anxieties of youth. The vacation is a metaphor for youth itself: sunny, fun, consequence-free, but always finite, always with an end point after which the vacationers will have to return to the real world, to work and responsibility and seriousness. That constant awareness of the end, which at first seems so distant and soon comes to loom very close indeed, is what makes the film so poignant, so bittersweet, so joyous and so melancholy.