François Truffaut's Day For Night is a love letter to the movies, a celebration of everything that happens on a film set, from the moment the director says "action" to the moment he says "cut" and everything that goes on around those boundaries, the personal dramas and business negotiations and constant attention to tiny details that all gets woven into the finished product of a movie. Truffaut himself plays a director making a movie, a melodramatic tragedy called Meet Pamela, and Day for Night is structured entirely around the production of the film within the film, with sporadic detours into the romantic dramas of the cast and crew, as well as the day-to-day logistical problems associated with making a movie.

The film is a love letter not just to the movies, but to a specific form of movies, the studio-bound big production. Truffaut at times seems to think he's making an elegy for a dead form of movie-making; his character, the director Ferrand, says in voiceover that this kind of movie is outdated, that from now on movies will be shot in the streets rather than on studio sets. Truffaut is offering a nostalgic look back at the movies made before the French New Wave came along, seemingly with the assumption that Truffaut and his compatriots had rendered these big productions and artificial sets obsolete. It's an elegy that, forty years later, seems more than a little premature, as Truffaut himself — who, whatever the merits of his work, hardly ever followed up on the radical promise of his shot-on-the-streets debut — should have understood very well.

Despite this misplaced nostalgia, the film is charming because it's so packed with the director's obvious love of the movies, his affection for actors, stuntmen, script-girls, props crew and makeup artists, even producers. There are countless little affectionate nods to the love of movies. The crew passes "Rue Jean Vigo" on the way to a shoot, there are references to everything from The Rules of the Game to The Godfather, and at one point Ferrand spills out a package full of books, all of them tributes to directors, including Buñuel, Hawks, Robin Wood's book on Hitchcock, even a book about Truffaut's fellow New Wave legend Godard, who had taken such a different path through the cinema, and with whom Truffaut had had a rocky relationship for years. (Godard, unsurprisingly, hated the film with its celebration of a studio-bound, craftsmanlike approach to the cinema, and the fallout from their angry letters about this film severed their friendship for good.)

Ferrand is also haunted by a dream of a boy stealing posters for Citizen Kane from a movie theater, a sign of how early in life the love of cinema manifests for these characters, and a nod to the director's continuing fascination with childhood. It's touching, even though Ferrand himself, haunted by dreams of cinematic greatness, hardly seems to be making an ambitious artistic masterpiece like Kane. Maybe Truffaut, whose own career was spotted with uneven, traditionalist love stories of the kind that Ferrand is making here, is suggesting that the charm and the pleasure of movies can be found in even some less satisfying and ambitious examples of the form. Just as Jean-Pierre Léaud's character, the actor Alphonse, is happy to go to the movies to see anything, Ferrand seems happy to be making a movie, any movie, and whether it's good or bad he'll be happy to have made it, to have created something from all this chaos and unpredictability.

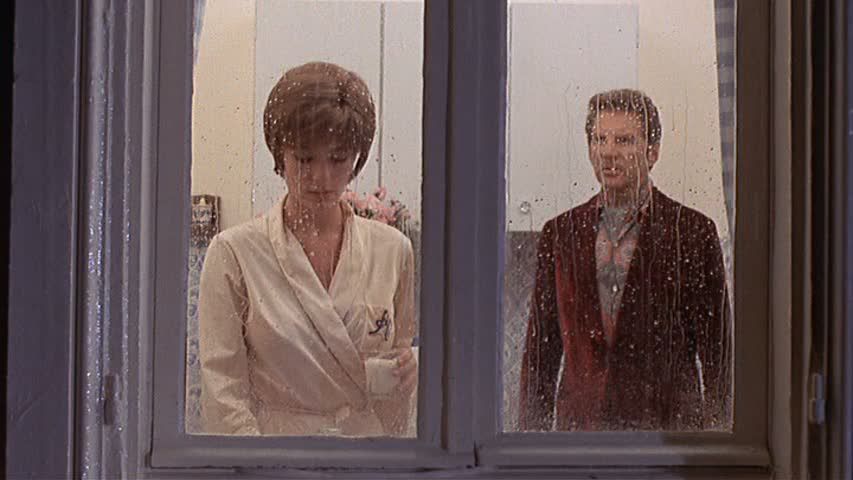

Where Truffaut really excels, as always, is in honing in on little moments of searing emotionality amidst the chaos. On this set, everyone is sleeping with everyone, and while much of this plays out as typical bed-hopping farce, there's also genuine pathos in the on-set romances, particularly surrounding the production's lead actress Julie (Jacqueline Bisset) and Léaud's Alphonse. Alphonse spends much of the movie angrily pining for his girlfriend Liliane (Dani), who promises she's his but takes every opportunity to sneak off into a corner with other crew members, and finally leaves the set entirely with a departing British stuntman. Julie, trying to calm Alphonse down and prevent him from storming off the production, winds up going to bed with him, a mistake she instantly regrets when the needy, emotionally immature Alphonse (a very similar character to Léaud's Antoine Doinel) decides that he loves her and calls her husband to tell him so.

After the fallout from this has played out, the subsequent scenes of Julie and Alphonse together are infused with a somber gravity, the unscripted emotions of their private lives seeping into the script, sometimes intentionally as when Ferrand writes some of Julie's private words into the script for her character to say. One scene in particular, in which Julie walks with a candle casting a warm glow onto her features, staring straight ahead at the camera while Alphonse caresses her face, seems loaded with the emotions from the actors' offscreen affair, reverberating with the equally troubled onscreen relationship of their characters, who are supposed to be married.

There is also a great deal of emotional subtext surrounding two actors who are meant to represent the dying studio system, the old way of doing things. Severine (Valentina Cortese) was a once-great actress who now seems to be falling apart, constantly drunk on set and barely able to remember her lines or her cues. (Hilariously, she says she's used to working with Fellini in Italy, where dialogue is generally dubbed, so all she had to do was recite numbers while performing.) Scenes with her are repeatedly reshot, often becoming more and more disastrous with each take as she becomes drunker and more inconsolable over her failures. At one point, she laments that she's growing older, that her contemporary and costar Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Aumont) is still getting roles as dapper lovers, while she gets cast in thankless parts as the jilted wife. There's a feminist subtext here about the differential treatment of men and women in the movies, but Truffaut, typically, briefly hints at the idea rather than really developing it; he's interested in stories, not ideas, which is always what separated him most decisively from Godard.

Alexandre himself is the other old-guard actor who embodies the film's nostalgia for old ways of doing things. Throughout the film, he's continually relating charming anecdotes about old Hollywood, about the quirks of the star system and the gossipy behind-the-scenes chatter that flows through the movie industry. At one point, as he relates one of these anecdotes, Truffaut's camera drifts in, probing towards a closeup as this actor waxes nostalgic about the glamour and magic of movies and Hollywood stars. Soon after, Alexandre, this symbol of the old era, is dead, in an offscreen car crash that might be a nod to Godard's own tribute to moviemaking, Contempt. Indeed, Contempt is an interesting comparison point in general. Godard's film is seemingly more personal in its focus on the emotional torment and romantic drama that gets woven into the production of a movie — Truffaut's bed-hopping dramas are low-key and tangential compared to the searing power of Contempt's apartment argument centerpiece — but Truffaut's film is personal in a different way. It's personal in the way it communicates a deep love of the movies that goes beyond the particular quality, or lack thereof, of a particular movie, to extend to the whole process of making movies, good or bad, ambitious or straightforward, commercial or arty.

Indeed, this is a film about, and probably for, people who love the movies, and live the movies as well. Alphonse wonders if the movies or life are more important, but for Truffaut — as for Léaud, and in his very different way for Godard too — the movies and life are intimately interconnected. And the movies, which transmute life into art, perhaps have the advantage. In one of the film's best and truest lines, the script-girl Joelle (Nathalie Baye), upon learning that Liliane has run off with a stuntman, says earnestly, "I'd drop a guy for a film. I'd never drop a film for a guy." One suspects that Truffaut, for all the romanticism of his movies, feels similarly.