The Castle was one of the novels Franz Kafka left unpublished upon his death, the unsettling story of a land surveyor who repeatedly and fruitlessly butts up against the unyielding absurdity of a labyrinthine bureaucracy in a snowy mountain village. Michael Haneke's 1997 adaptation of the novel is mostly faithful, both to the spirit of the work and often to its letter, liberally quoting from the novel in the narration that runs through the film. The novel is a masterpiece, one of Kafka's best and most richly layered works despite its lack of an ending; if Haneke's film is not quite as good, it's still an interesting adaptation with a lot to recommend it.

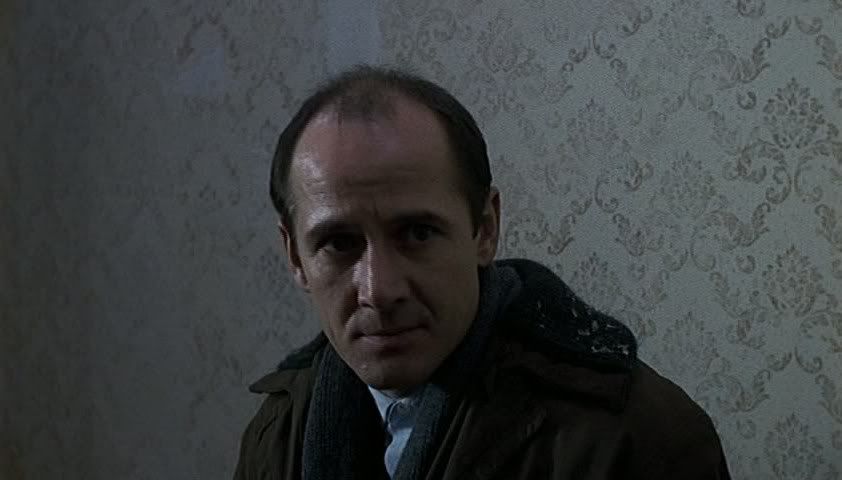

One of the characteristic features of Kafka's novel is its dense, repetitious prose, as the land surveyor K. (played by Ulrich Mühe in Haneke's film) tries to navigate a torturously complicated bureaucracy that denies ever having hired him for the post of land surveyor. The novel makes K.'s thought processes palpable, delving into his intense frustration, his stubborn determination to get past the seemingly insurmountable obstacles keeping him from satisfaction, his circuitous reasoning and obsessive rationalizations of his surreal dilemma. The novel is in the third person, but in its dense internality it often retains evidence of its origins as a first person narrative. Haneke removes much of this material, retaining only slices of the novel's narration and clipping out much of the connective tissue, with the result that the film is quite possibly even more disorienting than the Kafka source. The film's K. is far more unknowable than the novel's, his actions far more mysterious and strange, without all the explanations and rationalizations that weigh down every least action of the novel's central character.

At times, it's hard to know what someone unfamiliar with the novel would even make of this absurdist story, which so steadfastly refuses to flow smoothly from one moment to the next. Scenes begin and end abruptly, cutting to black as soon as a line of dialogue has been uttered. The film has a choppy, off-kilter rhythm that does a good job of capturing the strange qualities of Kafka's prose. K. plods through the snow, walking from nowhere to nowhere. K. meets with a succession of bureaucrats and people who he desperately hopes will have some connection to the Castle, even though his attempts never get him anywhere. He engages in an affair with a barmaid named Frieda (Susanne Lothar), because he believes that she too has some tenuous connection to the Castle. He suffers many indignities, and many confusions, and after a while he seems to forget what he even wants, why he's even trying so hard to get to the Castle.

Haneke presents this material with stripped-down faithfulness, alternating short, clipped excerpts with long monologues and dialogue, often shot with extended takes; this, too, contributes to the film's skewed pacing, with truncated snippets of scenes abutting lengthy, nearly verbatim exchanges from the source material. The visual aesthetic is rough and minimal, with the town that K. arrives in rendered as a somewhat shoddy rural village of an indeterminate time period, old-fashioned in atmosphere, with a horse-drawn carriage as the only transportation, but with modern appliances like the radio that's mysteriously switched on and off during the opening scenes. Outside, there's a snowy wasteland through which K. trudges in lengthy horizontal traveling shots that follow him through the snowbanks, the background often all but obscured by the wind, which kicks up miniature storms of fluffy powder. The Castle itself, tellingly, is never seen, even though it's virtually all anyone talks about.

Haneke, following Kafka, casts K.'s two assistants (Frank Giering and Felix Eitner) as darkly comic figures of mischief and grinning malice, much like the sinister villains of Funny Games, made the same year — Haneke even cast Giering in both films, as one half of the sinister pair, Tom and Jerry, Peter and Paul, Fatty and Skinny, and here Artur and Jeremias. More even than in Kafka, the assistants provide a bizarre strain of humor here, hanging around K. like a pair of slapstick buffoons, reading a letter to him in discordant unison, running around in circles in the snow and occasionally unleashing enthusiastic self-congratulatory cheers.

The film ends, like the novel, in mid-sentence — recalling the obsessive literary faithfulness of Eric Rohmer's Perceval le Gallois, another adaptation of an unfinished work — as K. gets himself tangled up with yet another potential connection, another in a long line of people who could help him, but probably won't. One of the crucial points of both film and novel is the way in which inhuman bureaucracy reduces people to a limiting self-interest, unable to develop meaningful connections except those based on getting what one wants for one's self. Naturally, that's a theme that resonates with Haneke in a big way, and the film dovetails nicely with the director's more personal work, underlining his typical themes of alienation and the cruelty generated by governmental and societal systems. It's a fascinating film, mostly because it's drawing on a truly complex and powerful book, but also because it reflects Haneke's

3 comments:

Fellini Satyricon also ends in mid-sentence.

As much as I love Fellini, somehow I still haven't seen that!

As does Roger Avary's adaptation of The Rules of Attraction!

Post a Comment