François Truffaut's Two English Girls is a moving, haunting, subtly powerful film, a drama of alternating repression and release, sexuality and restraint, purity and excess. It is adapted from what seems to be a rather melodramatic novel by Henri-Pierre Roché, who had also written Jules and Jim, another novel about a love triangle that Truffaut had famously adapted. This second consideration of the theme reverses the situation. Where Jules and Jim was about a woman torn between two men, this film, like the novel it's based on, is about a man and the two women he loves. The film is full of melodramatic contrivances and over-the-top emotions: women faint dramatically while reading letters, lovers are torn apart by solemn pacts, there are hysterical pregnancies and illnesses that seem as much psychological and emotional as physiological.

Truffaut alternately revels in these intense emotions and keeps them at arm's length: like the characters, the film and its director seem torn between repression and release, unsure whether to give in fully to the madness and ecstasy and pain of these emotions or to hold back, to retreat into asceticism. The effect is enthralling and ambiguous, rendering these melodramatics affecting and overwhelming when seen, veiled, through the filter of Truffaut's uncertain distance, his hesitance to fully embrace the passions and excesses of this lurid, tragic romance. Claude (Jean-Pierre Léaud) is a typically fickle and promiscuous young man when he meets Ann (Kika Markham), a young English girl visiting France. He's drawn to her, but their relationship remains chaste and friendly, even though Claude is undeniably attracted to her; he calls her his "sister" but thinks about grabbing her hand, about kissing her. She takes him to visit her home in Wales, where she introduces him to her sister Muriel (Stacey Tendeter), who she's clearly pushing towards Claude despite her own feelings for the young man.

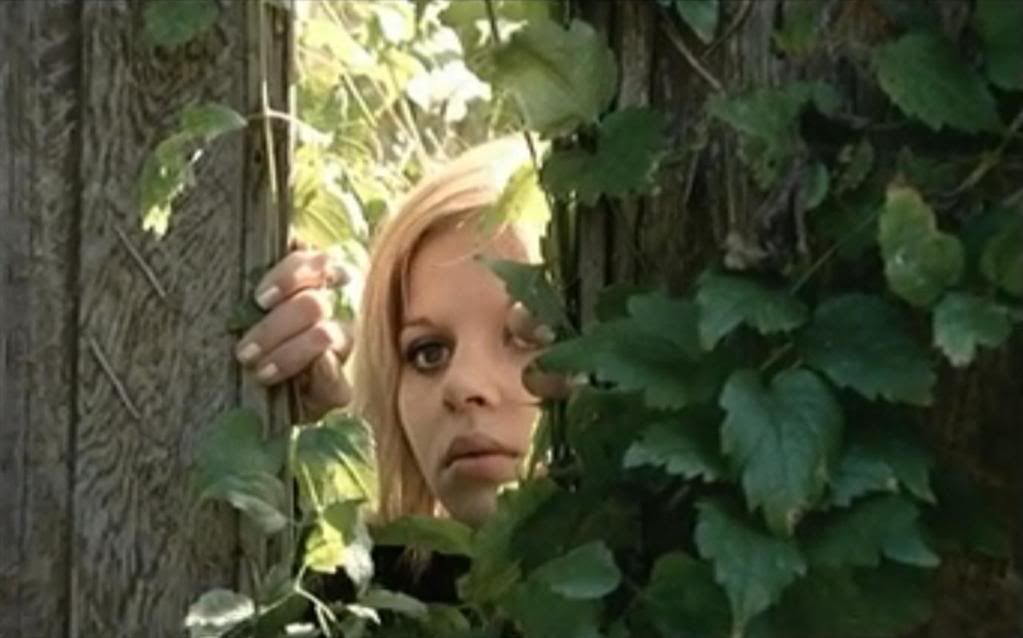

Muriel is built up before her first appearance; at times it seems as though Ann can speak of nothing but her sister, who remains curiously out of view, her absence consistently emphasized in Truffaut's mise en scène. Her closed door, with Muriel sleeping inside, is lingered over. Her empty place setting at the dinner table becomes a point of fixation for Claude. When the girl finally appears, she's sitting stiffly at the table with bandages wrapped around her face, protecting the fragile eyes that she has strained reading. The glimpses that Claude gets of her eye as she lifts the bandage seem to provoke him and arouse his curiosity even more.

Throughout the film, this tension between Claude and the two sisters keeps erupting in different ways, their loves for one another warped and held back by both their own individual moralities and the societal conventions that keep feelings buttoned up. In many ways, the film is about the erosion of a hypocritical and artificial sexual morality that privileges virginity and "purity" in women while condoning the flighty affairs and indiscretions of men. Both of the sisters, in their different ways, strain against this hypocrisy, and it's the women in the film, not the inconstant and indecisive Claude, for whom Truffaut seems to have the most sympathy. Muriel throws herself into religion, finding an outlet for her feelings in devotion to God, denying sensuality and worldliness: at the peak of her devotion, she's moved to confess, in an astonishing journal that she sends to Claude, that she has a weakness for masturbation that was inculcated in her by a childhood lesbian fling with a friend. In spite of that, she is suspicious of the body, suspicious of physicality, and in that she's the opposite of her sister Ann, who initially seems as repressed and proper as Muriel, but soon reveals a more worldly side as she becomes a sculptor, a world traveler and, eventually, Claude's lover.

Their relationship mostly just exposes Claude's hypocrisy, as he introduces her to his ideas of "free love" but is then clearly heartbroken when she takes him at his word and begins seeing a second lover. Claude is a rather callow young man, and Truffaut is unsparing in his depiction of Claude's mistreatment of women. He has romantic ideas, but they mostly seem to be about himself, about the kind of romantic artist's life he wants to lead, rather than about the women whose love he takes for granted and whose passions he awakens and discards.

Truffaut deftly balances the extreme emotionalism of this story, with all its twists and turns and shifting loves, by alternating between bursts of emotional catharsis and stretches in which feelings remain as buttoned up as the exterior the characters present to the world, making it difficult to know what they're thinking or feeling. The effect is striking. Claude's initial time spent with the two sisters in their home is especially spartan and restrained, with Truffaut keeping his distance as Claude vacillates between the two sisters, while Ann is clearly pushing him towards Muriel. It's not clear at all what any of them are truly thinking or feeling, perhaps because they don't know for sure themselves.

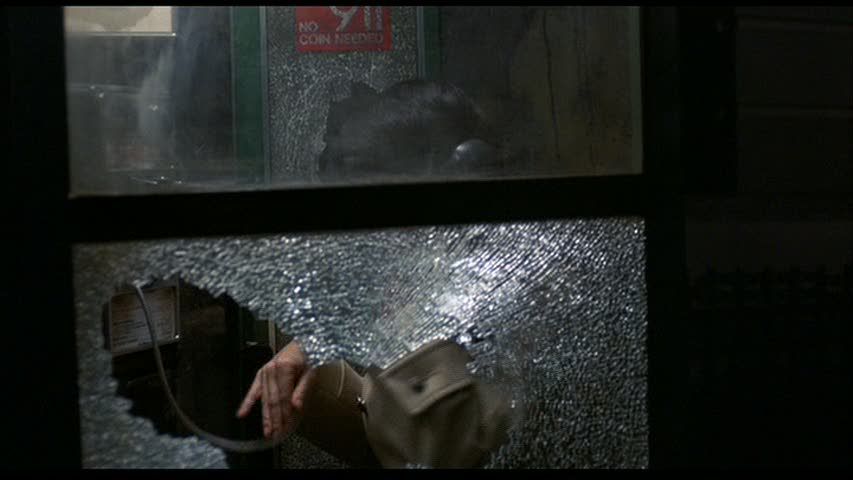

This coolness and detachment is especially effective when it's followed by the occasional raw expressions of deeper feelings that punctuate the film. After Claude abruptly breaks off his engagement to Muriel, a decision that barely seems to affect him, Truffaut cuts Claude out of the picture to focus on the suffering of Muriel when she receives his cold-hearted letter. She writes a series of letters in response and never sends them, pouring out her heartbreak and pain on paper and in the film's voiceover, and then, after all this anguish has exploded messily across the film, Truffaut finally cuts back to Claude in Paris, receiving a cool, reserved, polite, understanding letter from Muriel in which she fails to mention any of the pain that he had caused her.

This is the heart of the film, this gap between the surface and the depths, between the polite face presented to the world and the secret turmoil and strong feelings and conflicted desires that lurk underneath. Truffaut deftly balances the two here, and in the process displays a far greater understanding of love, lust and loss than he ever did in Jules and Jim — that the earlier film is acclaimed while this probing, complex work is not is clearly an injustice. The tension is embodied also in the contrast between the film's literary source — the opening credits roll over images of Roché's novel, the pages dense with scrawled notations — and the cinematic, visual splendor of Nestor Almendros' images. The film is both dazzlingly cinematic in its sensuality and its visual beauty, and literary in its frequent reliance on voiceovers that alternately express forbidden feelings or lie to cover up those feelings. Sensual, emotionally rich, ambiguous and ultimately bittersweet, Two English Girls is one of this director's greatest statements on tragically denied love.