Béla Tarr's

Sátántangó is an extraordinary film, gorgeous and haunting and full of unforgettable images. Even at seven-and-a-half hours long, the film is never less than enthralling, and each deliberately framed and choreographed shot is jaw-dropping, even when nothing much is actually happening within the frame. Though Tarr isn't very concerned with narrative, there is a story of sorts here, a loose one divided into twelve chapters that overlap one another chronologically and show the same scenes from different points of view as different characters' stories intersect over the course of a couple of days. The film is set in a tiny rural Hungarian village at the start of the autumn rainy season, which the villagers are now prepared to endure, miserably, until springtime. The town is grim and ugly, a few crumbling buildings spread out across the barren, dismal countryside. The place is soggy and knee-deep in mud, and it's constantly pouring, rain streaming down the grimy windows and soaking the villagers whenever they trudge through the muddy fields that surround their homes. As the film opens, the villagers have sold off their communally owned cows and are planning to split the money and abandon the village, all of them heading off to their own personal escapes.

Naturally, they're all scheming against each other, some of them planning to steal all the money and escape on their own, until their plans are all disrupted by the return of Irimiás (Mikhály Vig, who also provides the film's eerie, minimalist music), a messiah-like con artist who'd been reported as dead a year and a half ago, but who had really been in prison with his friend Petrina (Putyi Horváth). This duo's return to town disrupts all the villagers' schemes, filling them with mingled hope and fear: they know that Irimiás will have some grand plan for their money, but it's not clear if they welcome this opportunity to be shaken out of their ruts or mourn the likely loss of their long-awaited windfall to the rogue's latest brainstorm.

This tense anticipation dominates the film's first half. Irimiás and Petrina do appear in one sequence early on, but other than this, they're spoken of more than seen for the first several hours of the film. Tarr observes how the villagers await the arrival of the mysterious duo, going about their dull and listless lives in the meantime, boiling over with frustration and confusion as they wrestle with their feelings about the returning troublemakers. Tarr's preference for long, unbroken takes — either static or slowly tracking — enhances the elongated expectation. The film is "about" its duration as much as anything, about the way time passes, about the long dead moments and empty spaces that make up a day. The film's epic seven-and-a-half hour length places the viewer in the same position as the villagers, enduring long periods of stasis and nothingness, long

temps mort accompanied only by the buzzing of a fly or the loud, repetitive ticking of a clock in a depressing local bar.

The film opens with a long shot of a field of cows, the soundtrack dominated by their mooing and a droning tone in the background. Eventually, the camera begins to track sideways, away from the field, gliding along past a long wall, examining the crumbling plaster and cloudy, filthy windows that offer no view into the rooms inside. The camera's movement is slow and steady, and when it finally reaches the end of the wall, it looks out again at the cows, milling around in a courtyard in the distance, watching until they all wander away, out of sight around the corner of a building, leaving behind only a chicken strutting across the muddy open space until the image fades to black. It's a fitting introduction to the patient, unshowy aesthetic of Tarr's epic, its careful observation of the minutiae of daily life and its attentiveness to the matter of time.

Later, Irimiás and Petrina wait in a town office, and Irimiás comments that there are two clocks, neither of them correct. He poetically connects this temporal confusion to the "the perpetuity of defenselessness," before adding, "We relate to it as twigs to the rain: we cannot defend ourselves." That's the essence of Tarr's perspective on time, this relentless forward flow that cannot be paused or halted, that is always charging onward regardless of what's happening in any individual life. The emphasis on the passage of time is so essential because one of Tarr's key themes here is stagnation: time passes, and yet nothing happens, everything remains the same, the people of this town continue to wallow in misery and boredom, to simply pass the time.

Futaki, dreaming of fleeing the town with his share of the money, wants only to rent a farm where he can do nothing all day, only watch "this fucking life" go by while he soaks his feet. When Irimiás and Petrina return to town, their young hanger-on Horgos (András Bodnár) fills them in on what the town is like now — which is to say, that nothing's changed, that everything is exactly as it was a year and a half ago when they left. In this context, Tarr's deliberately eventless static views and snail-paced tracking shots accentuate the numbing, narcotic pace of everyday life in a place where nothing happens, and where even the wildest dreams of the inhabitants are boring and routine.

At other times, though, Tarr finds strange beauty and even heroism in the mundane. A drunken old doctor's (Peter Berling) trip to refill a jug of fruit brandy becomes an epic journey across the wasted countryside of the village. He staggers and stumbles through the muddy fields, the rain pouring around him, the soundtrack composed only of his heavy breathing, his raspy coughs, his burps, and the plodding steps of his feet, sticking in the mud that covers both the roads and the fields. As it gets dark, the doctor's form is increasingly hidden in the unlit night, his silhouette occasionally highlighted against the distant lights of a house or the local bar. As the doctor approaches the bar, wheezing accordion music can be heard, the first hint of the drunken revelry that will play out in later scenes inside the bar. The doctor just passes by, though, staggering into the woods, glimpsing the dark trio of Irimiás, Petrina and Horgos purposefully walking by on the nearby road. Tarr makes this simple journey across a small distance seem epic, overwhelming, taking every ounce of will and strength from this unhealthy, unhappy old man. That's another aspect of Tarr's extended duration: this is an epic of the everyday, an epic of short distances, because this town and its muddy, pathetic territory is the full extent of what these people know, it is the setting for their entire lives and thus it

must be epic, because everything they are and everything they do plays out here, and a trek to get some alcohol can seem as important as Odysseus' journey home, while a short cigarette break with some plump prostitutes takes the place of Odysseus' many detours and obstacles on his way back to Ithaca.

There is an obvious political dimension to the film, as well. Tarr had wanted to adapt Lázló Krasznahorkai's novel since the 80s, but he had been unable to do so because of the threat of censorship from the Hungarian Communist government. It doesn't take much reading between the lines to see that the film is a bitter satire of the failures of communalism, exposing the ways in which, while supposedly working communally towards a common purpose, people remain atomized and isolated, concerned far more with their own selfish interests than those of the group. Irimiás himself is the most obvious symbolic representative of Communist ideas. He calls himself "a servant of a great cause" and organizes people for his schemes, but the dreams of communal success that he stirs up in others are simply smokescreens for his cons and tricks. He says he's bringing people together but he actually tears them apart and scatters them, breaking up their community under the guise of rejuvenating it. The idea of working together for a common goal is a lie, a ruse, a distraction from the essential miserableness of these people's lives. They have no sense of real control over their lives — they are defenseless, a theme that percolates throughout the film — and Irimiás' grand rhetoric gives them an illusion of power, however misguided. Really, they are defenseless before him as well.

One of the film's most notorious extended scenes is the one where a young girl (Erika Bók) tortures a cat and then kills it by putting rat poison in milk. She feels hopeless, bored, abandoned, by a family that doesn't seem to care about her much, and she takes out her own torment on her defenseless pet before killing herself as well. It's an uncomfortable sequence to watch, and not only because of its implications for the characters and themes. Tarr insists that the cat was treated humanely and not truly harmed, but it's still discomfiting to see the girl flail around, swinging the cat around with her, then trapping it in a net and shoving its head into a bowl of milk. Such moments in a fiction film always shatter the illusion of a story being acted out. It's too real, and too cruel, forcing one to think not about the cruelty of this girl, whose feelings of impotence lead her to assert her power over a defenseless animal, but the cruelty of the filmmakers who demanded that the scene be shot in this way, that these things should be done to a real, defenseless living thing.

The penultimate chapter of the film resumes the commentary on the political dimensions of Irimiás' actions. This segment consists entirely of two bureaucrats translating Irimiás' vile, hateful letter about the townspeople into more discrete and official language. Nothing can be said directly, so they have to come up with euphemisms for everything, replacing "fat sow" with "overweight," and "wrinkled worm, filled with alcohol" with "elderly alcoholic, short of stature." This sequence is rich in bitter humor, mocking the bureaucratic circumspection of these office drones while also revealing the full extent of Irimiás' deceitfulness. At the same time, Tarr focuses on the humanity of the bureaucrats, whose work — cleansing language of its richness and idiosyncrasy, reducing words to a generic gray pulp — wears them down daily. They take a break from their work at one point, sitting down away from the typewriter to have a snack, eating in silence. While they eat, they drop their businesslike demeanors, and suddenly they are just men, requiring a break from the soul-numbing stupidity of their work. When they're done eating, unfortunately, they must return to the typewriter.

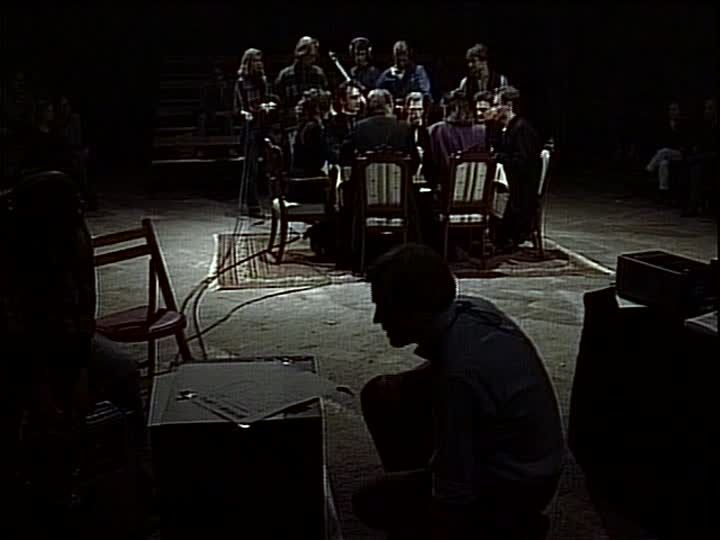

Tarr often enlivens the film with subtle, bittersweet humor like this. One key sequence is the lengthy drunken dance where the townspeople, anxiously awaiting Irimiás' arrival, clumsily dance and grope one another. The scene lasts around half an hour, with the repetitive accordion music wheezing out its incessantly bouncing melody, as the revelers sway and careen off one another awkwardly. The cast was really as drunk as they seem to be onscreen, lending an air of verisimilitude to their staggering steps and lunges at one another. They seem angry one moment, joyous the next, their minds clouded, erasing themselves in this celebration. In the chapter title that precedes this segment, Tarr deems the dance the "sátántangó" from which the film takes its name, and indeed there's something apocalyptic and desperate about everyone's flailing about, their wild abandon. But it's also amusing and powerful, a rare moment of celebration in the lives of people who don't often have much to celebrate. At one point, the camera pans around the room and finds one married couple eating from opposite ends of a cheese bread, devouring it like Lady and the Tramp romantically eating spaghetti together, a hilarious and ridiculous image, if also a grossly romantic one.

Petrina is also a rich source of comedy, playing a dopey comic foil to the messianic Irimiás, even in terms of appearance. While Irimiás is striking and foreboding in his dark trenchcoat, Christ-like beard and fedora, Petrina looks like a dumpy reject from the Three Stooges, a woolen snow cap pulled down tightly over his egg-shaped head. In a mysterious scene late in the film, Irimiás, Petrina and Horgos are walking along a road through a sparsely wooded area. Suddenly, Irimiás stops and falls to his knees in the middle of the road, staring forward as though overcome with sublime religious awe. He watches as a cloud of fog rolls past, obscuring a ruined building, then blowing away in the wind. Tarr never explains this moment or the image that prompts Irimiás' awe; it's left as a beautiful and eerie image of the huckster being overcome, momentarily, by seemingly genuine sentiment. Then Petrina breaks the mood, as the trio walks away, by irreverently asking, "you've never seen fog before or what?"

Irimiás is often associated with nearly mystical, awe-inspiring incarnations of nature. In one of the film's best shots, Irimiás and Petrina walk along a road through town as garbage flies along the ground around their feet, the wind whipping paper, cardboard boxes and other debris through the narrow path between houses. It's another somewhat apocalyptic image that's strikingly beautiful as well, capturing the stark, weather-beaten conditions of this town, but also making even this barrage of trash seem graceful and elegant.

The film is packed with gorgeous, unforgettable images like this, like the remarkable shot that keeps circling around the sleeping figures of the townspeople in the manor they've moved to at Irimiás' behest. As they sleep, and the camera twirls, the voiceover recites the dreams and nightmares of the villagers, haunted in their rest by strange visions, confused erotic fantasies, and fantastic hopes. It's a deeply affecting extended shot, because Tarr's film is all about the hopes and dreams of these ordinary, downtrodden people — and the ways in which those dreams are destroyed and corrupted by the cruel world they inhabit and the societal strictures that govern even their most secret dreams.

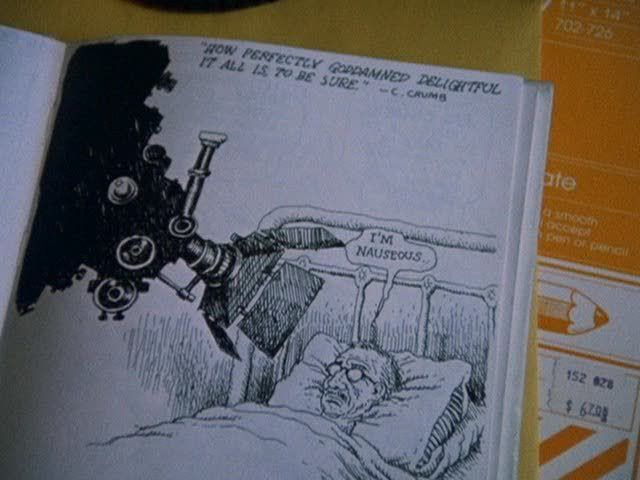

In the film's devastating final chapter, those dreams seem to take tangible form, writing a surreal nightmare onto the landscape of the territory as Tarr returns to the elderly doctor. He once again wanders off into the landscape, but this time, instead of stolidly plodding through the muddy fields in real time, he gets swallowed up by a strange vision, chasing the distant sound of bells to a wrecked church where a mysterious and cadaverous-looking man repetitively rings a bell and shouts. It's a strange and unsettling end to a remarkable film, and the final shot, in which the doctor slowly removes every trace of light from the image by boarding up his windows, chronicles the slow process by which the film disappears into the nothingness from which it came.