Martin Scorsese has made a commercial for the Spanish wine company Freixenet, which normally wouldn't be very notable to me, except that it's not so much a commercial as it is a 9-minute short film, called The Key To Reserva, Reserva of course being the wine in question. Scorsese took the opportunity and ran with it, clearly having a blast as he turns his commercial into a funny and detail-packed tribute to Alfred Hitchcock. It's a joy to watch, a witty tribute that any Hitchcock admirers should be sure to check out. The short, which is available online from Freixenet's website, begins with Scorsese explaining, in faux-documentary introduction, how he's discovered a three page excerpt from a Hitchcock film which was never made. And in a feat of film preservation that would be the first of its kind, he intends to preserve this unmade film, by of course making it himself. There follows the film itself, which makes a bottle of Reserva wine the MacGuffin for a series of hilarious and dead-on tributes to various Hitchcock films, from the Saul Bass-esque opening titles to the concert hall scene of The Man Who Knew Too Much to the gravity-defying denouement of Saboteur to the wine-cellar scene from Notorious. There's even a cameo appearance by the memorable R.O.T. monogram from North By Northwest, and the countless other Hitchcockian gags crammed into every second are guaranteed to make the film connoisseur smile. The final tribute to The Birds is the most impressive of all, using a crane shot pulling back from a building (the reverse of the one from the beginning of Psycho) to reveal a cityscape covered in threatening black birds. The fact that a Spanish company seems to be OK with such an expensive, elaborate, and in-jokey commercial just to sell a bottle of wine is pretty amazing, but then again it's already getting their name out there, so maybe they know best. In any case, it's a great, fun little diversion, definitely worth a look.

By now, the plot of Douglas Sirk's All That Heaven Allows should be very familiar, considering it has been adapted for both Fassbinder's Fear Eats the Soul and Todd Haynes' Far From Heaven. It's the story of the lonely widow Cary (Jane Wyman), who falls in love with her younger gardener Ron (Rock Hudson), and plans to marry him despite the differences in age and social class which put external pressures on the relationship. As a satire of upper-middle-class pettiness and hypocrisy, it occasionally lays it on too thick, a hallmark of Sirk's work that nevertheless contributes to his satire's biting wit. As the gossip and snarky jokes and open disapproval of Cary's friends, neighbors, and even children begin to weigh on her, the relationship seems less and less stable or possible. Sirk's portrayal of these ungenerous souls is unremittingly caustic, with a devastatingly sharp satirical eye that never fails to capture the bitchiness and jealousy hidden beneath the ever-present phony smiles and friendly banter.

If Sirk's satirical touch can sometimes be heavy and unsubtle, his visual sense is unfailingly exactly the opposite. Here, his style is most effective in contrasting the harshness of his high society satire with the lush warmth of his visuals, especially in the scenes set at Ron's country retreat. Ron's lifestyle evokes the pastoral philosophy of Henry David Thoreau's Walden, which is quoted from in one scene. Ron's true-to-himself philosophy and rugged life, continually in touch with nature, is a stark contrast to the hermetically sealed spaces of Cary's old-money mansion, her dead husband's ancestral home and a constant reminder of her widowhood. Her daughter Kay (Gloria Talbott), a social worker who provides some of the film's funniest comic relief in her straight-faced presentations of Freudian psychobabble, tells her mother about the old, outdated Egyptian custom of entombing the wife with her dead husband so she might enter the afterlife with him. That custom is long gone, the daughter assures her, but Cary isn't so sure, and with good reason. What is her house but a brightly lit tomb, with her dead husband's possessions all around her? And the townspeople are only too glad to make sure she stays in this tomb, alone and unhappy, unless of course she decides to marry a socially acceptable man like the much older Harvey (Conrad Nagel), who lacks passion or emotion but offers her at least, in his dry way, "companionship."

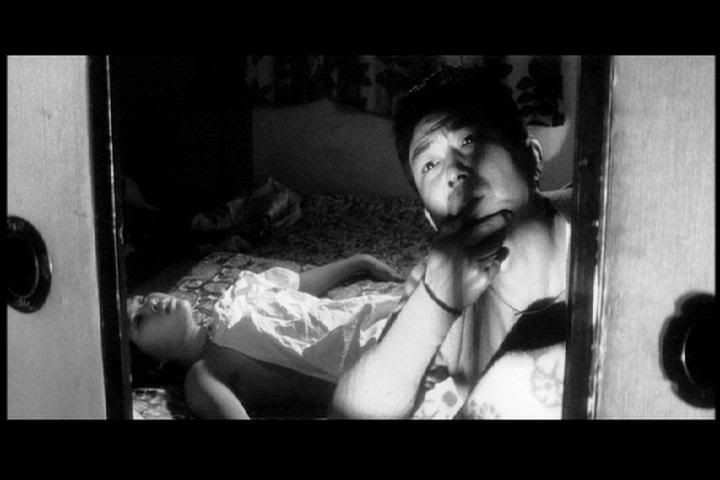

The idea of the dead's possessions comes up again when she decides to marry Ron and begins packing away some of the more visible reminders of her status as a widow, including a trophy that had long sat on the living room mantle. When her son Ned (William Reynolds) discovers this, he's enraged, and he corners her later on for a late-night argument, in which he winds up next to the mantle, the trophy a conspicuous absence next to him, with two urn-like vases framing the empty space. Sirk does everything he can to draw attention to this absence, making the scene's focal point the disappearance of the trophy, while neither Ned nor Cary makes any mention of it during the course of the conversation. They're talking about Cary's impending marriage and Ned's feelings about it, but implicit underneath it all is the implication that Cary is trying to leave her husband's tomb, that she's putting away his possessions and forsaking her caretaker status.

It's this kind of subtextual visual touch that sets Sirk apart. He's working, as always, with a somewhat over-obvious and melodramatic script, with Kay a perfect vehicle through which to explain the characters' psychological motivations. She's often lampooned within the film for her ready explanations, which she wields like a shield even in a romantic encounter, but the script also uses her as an all-purpose explainer to draw out emotions that Sirk rendered perfectly well through his mise en scène. Thankfully, the love between Cary and Ron is left unexplained, in a rare moment of restraint from the script. Their love requires no better explanation than the quiet moments they share in front of the frosty blue glass of the window in Ron's home, looking out on a glorious winter snowscape. These moments abound in this film, as Sirk clearly sides himself with Ron's closeness to nature and quiet romanticism. In the film's final scene, when Cary finally comes back to Ron after all the troubles they've endured, their reconnection is symbolized by a reindeer that walks right up to the glass window that earlier backgrounded their most intimate moments. This is another potent melodrama from the master of such films, possibly the only director in the classical Hollywood era able to elevate such lurid women's pictures above the level of their writing through the sheer force of his visual expression and sensitivity towards his characters.

Vera Cruz is Robert Aldrich's rollicking adventure film set in the midst of the Mexican revolution against the emperor Maximilian. Among the American mercenaries heading south to get in on the fighting (and the monetary rewards) are Joe Erin (Burt Lancaster), a vicious bandit with a trust-no-one credo, and Ben Trane (Gary Cooper), a former Confederate officer and plantation owner who just wants money to rebuild his shattered life in the aftermath of the Civil War. These two unlikely compatriots team up, and even enter into an uneasy friendship, as they jockey for control of a massive cache of gold in the care of Maximilian's forces. It's a film of treachery and shifting loyalties, complicated by the addition of Denise Darcel as a shady countess not above using her considerable charms to blind men to her schemes, and Sara Montiel as the feisty Spanish girl whose sympathies lie with the rebels.

The film may locate the western genre south of the border (the better to stereotype its Mexican inhabitants), but otherwise it's a pretty typical example of the buddy western, with two diametrically opposed friends united by a common cause. Cooper's tough but moral Southern gentleman and Lancaster's sneering, dirty-dealing thief can't remain friends for long, and the film builds considerable suspense around the question of who's going to betray whom first. Aldrich's characteristic interest in the immorality and bluster puts the focus squarely on Lancaster, whose leering, over-the-top performance carries the film. Cooper plays the straight man in comparison, stolid and quiet as ever, letting Lancaster's gleeful amorality dominate the film until the inevitable final showdown necessarily pits the two opposing philosophies against one another. It's a predictable Hollywood western in so many ways, and Aldrich hardly does to the western what he did to the noir in Kiss Me Deadly. Lancaster and Cooper are the two competing visions of the American masculine archetype, the bad boy and the tough quiet one, but there's no deconstruction of these archetypes, just the celebration of their ultimate on-screen avatars. Still, it's a fun enough film in this vein.

More damning is the apparently slapdash quality of the editing, especially in the fight scenes, where awkward edits continually try to conceal the fact that the film's stunts and fight choreography were woefully inadequate. These obvious mid-action cuts have the effect of disrupting the space of the battle scenes, entirely breaking any illusion of continuity between the opposing sides and deflating the sense of excitement. If this was done with more rigor or intentionality, it could be seen as a deconstructionist gesture on par with the critique of Mike Hammer in Kiss Me Deadly, but in this film it just comes off as sloppy and shockingly amateurish in an otherwise polished and traditional production. Even with these failings, Vera Cruz isn't a total disappointment, and as a light 50s Hollywood entertainment it certainly does its job. Aldrich would go on to much better work only a year later, though, so in the context of his career this is a minor early entry, already showing evidence of his interests but still not as self-assured or distinctive as his best films.