Pedro Almodóvar's Law of Desire is a very strange movie, perpetually stuck between genres and never quite settling into any one mode for long enough to make a real impact. It's often entertaining — and even more often so bizarre that it's at least hard to look away — but in the end only isolated moments linger beyond the ephemeral moment. It's a dark comedy that isn't actually very funny, a melodrama so ridiculous it challenges even daytime soap standards of believability, a half-hearted murder thriller whose villain is one of the film's goofiest characters. And so on... Through all this wackiness, Almodóvar never quite dismisses the possibility that he actually means for this to be a moving drama, but then he'll follow up a genuinely touching moment of emotional depth with something so silly that it becomes impossible to take anything here seriously. It's a confused (and confusing) pastiche, and admittedly a rather fun whirlwind ride despite its flaws.

Almodóvar changes the seeming story as often as the film shifts moods, but it's basically about the famous gay film and theater director Pablo (Eusebio Poncela), who pines for his absent lover Juan (Miguel Molina) even as he starts up a fiery new relationship with the clingy, insistent Antonio (Antonio Banderas), who maintains that he's always been straight but who jumps wholeheartedly into this gay relationship anyway. The film sometimes seems to be about this romantic triangle, with Pablo still in love with Juan, angering the possessive Antonio. And sometimes the film is about Pablo's sister Tina (Carmen Maura), a transsexual who stars in his films and plays. Frankly, whenever the focus is on Tina, this suddenly becomes a much more interesting film. The young Banderas, still several years from his Hollywood breakthrough, brings a playful nuttiness to his part, and he's fun to watch, but Maura's tempestuous, flighty performance is a true wonder. Tina is a rich, unforgettable character, much more nuanced and memorable than Pablo, the film's ostensible protagonist, or anybody else in the film; she steals the film from everyone. Her backstory is complicated and absurdly melodramatic, and doesn't spill out until towards the end of the film, but what's obvious throughout is that she's a damaged woman who's given up on romantic, sexual love long ago. Instead, she pours herself into her love for her brother, and for the little girl she's adopted, the feisty Ada (Manuela Velasco).

Tina possesses surprising depths of religious feeling, even if she does practice a religion pretty much of her own making: she and Ada build a lavish shrine to the Virgin Mary in their living room and pray to the statue for very personal intercessions, all of which, from Ada's wide-eyed point of view, promptly come true. The film's sense of spirituality is as cock-eyed as everything else about it, but there's a certain profundity to the scene where Tina, entering a church where she sang as a young boy, abruptly bursts into operatic song, singing along soulfully with the priest at the organ. It's in Tina that the film's emotional core is located, in her poignant feelings about her tortured past and her distrust of men. Her history suggests that she's Almodóvar's version of Fassbinder's Elvira from In a Year With 13 Moons (she even gets her sex change in Morocco, like Elvira), but she's ultimately much more comfortable in her skin, and her chosen gender, than Fassbinder's character. She's a real woman in every way, and of course it helps that she's played by a real woman, too. Almodóvar even makes this into a subtle joke when he introduces Ada's biological mother, played by the very convincing real-life transsexual Bibiana Fernández, who is only given away by her deep bass voice, with its surprising resonances emitting from her distinctly feminine form. The "real" woman plays a transsexual and the real transsexual plays a mother, one of the many ways in which Almodóvar slyly pulls the rug out from under things.

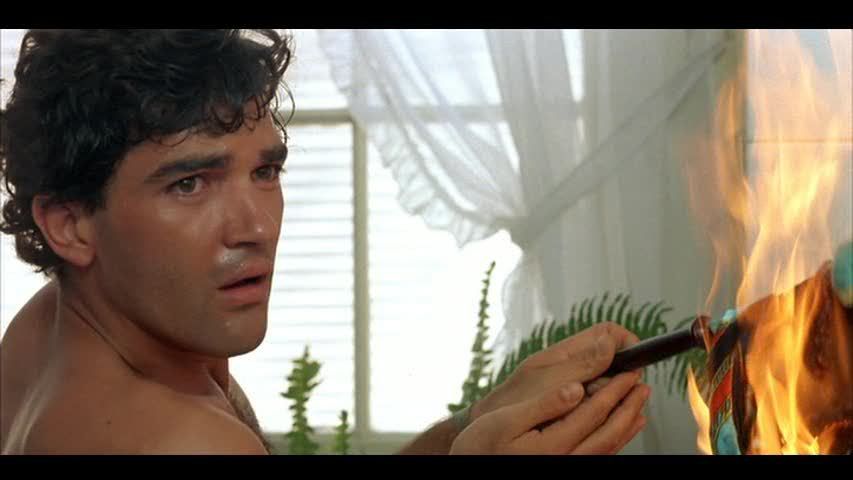

If Tina's story is often moving and beautiful and funny, the rest of the film sometimes seems to be struggling to come up with something equally compelling whenever she's not on screen. Poncela is wanly effective as the reserved, egotistical Pablo, dealing with two men while trying to bring together his latest project. But his story just isn't that interesting, and it goes completely off the rails in the film's second half when Antonio's increasing obsessiveness introduces some low-key thriller elements, even as the melodrama begins spiraling out of control. By the time Pablo winds up in a hospital, a total amnesiac after a grief-stricken car accident, one can only laugh at the craven silliness of the plotting. Even less explicable is Pablo's late-blossoming love for the batty Antonio, which renders the over-the-top final scenes utterly laughable — and really, what other response is there when Pablo's emotional outburst seems to cause the spontaneous combustion of his typewriter and Tina's shrine to Mary? It's as though the film has suddenly and incongruously morphed into one of those action movies where something is required to burst into flames in every scene, whether it's plausible or not.

The film is undoubtedly a mess, but an entertaining mess at least, and Almodóvar's visual style is never less than striking. He crams the film with playful stylistic touches, like the fade from a closeup of Pablo's eyes to the spinning wheels of his car, the hubcaps aligning perfectly with his pupils. There's also the sensual beauty of a wonderful scene where Tina, Pablo and Ada walk beneath the glistening arc of a hose's spray, marveling at the ethereal beauty of the water's perfect arc until Tina demands that she be soaked by the spray. The trio are a rough surrogate family, decidedly non-traditional but more loving and stable than the supposedly more conventional family Tina and Pablo had as kids themselves. Even while trapping this makeshift family within an increasingly outrageous and silly narrative, Almodóvar shows great respect for their nobility, their strength, their emotional riches. The film often seems on the verge of falling apart, but Tina, funny and fierce and independent and one of the cinema's great characters, never does.

1 comment:

I haven't seen this one. But I read your opening paragraph and that's all that I needed to know. Nice job.

Post a Comment