Melinda and Melinda starts with a premise that might be derived from a college creative writing exercise. A group of people, talking over dinner, begin debating whether life is essentially tragic or comedic. Two of the men (playwrights — one a tragedian and the other a humorist) try to prove their respective points by taking the same facts of an anecdote and telling the story two ways, once as a tragedy and once as a comedy. It's an obvious formal exercise, a writer's conceit, and Woody Allen seems to be in an experimental mood by expanding it from a sketchbook exercise into a feature film. The result is an interesting, uneven film anchored by an astonishing central performance — Radha Mitchell as both versions of the titular Melinda, the only character to exist in both versions of the central story.

This story's basic outline consists of a triggering incident when the distressed Melinda stumbles into a dinner party. In the tragic version, she is worn out and fidgety, recovering from a suicide attempt and trying to forget the disintegration of both her marriage and the affair that ended it. She drops in unexpectedly at the apartment of her old friend Laurel (Chloë Sevigny), who is entertaining a theater producer who may be able to offer a job to Laurel's out-of-work actor husband Lee (Johnny Lee Miller). In the comic take on this scenario, Melinda is actually in the midst of committing suicide, stumbling into the apartment of her neighbors, the indie movie director Susan (Amanda Peet) and her struggling actor husband Hobie (Will Ferrell). What's striking is that the scene doesn't play out that much differently from the tragic one, with the exception of a tossed-off gag about Susan's insistence that her guests continue to eat while she and Hobie try to help their neighbor. This underlines the problem with the film: though it attempts to create a contrast between tragedy and comedy, the comedy here just isn't that funny, consisting mostly of reheated lines familiar from Woody's schtick in countless other films. The opposition of comedy and tragedy here is as superficial as giving the comedy a happy ending and the tragedy a sad one, without really delving into the interesting questions about why we find humor or pathos in various situations.

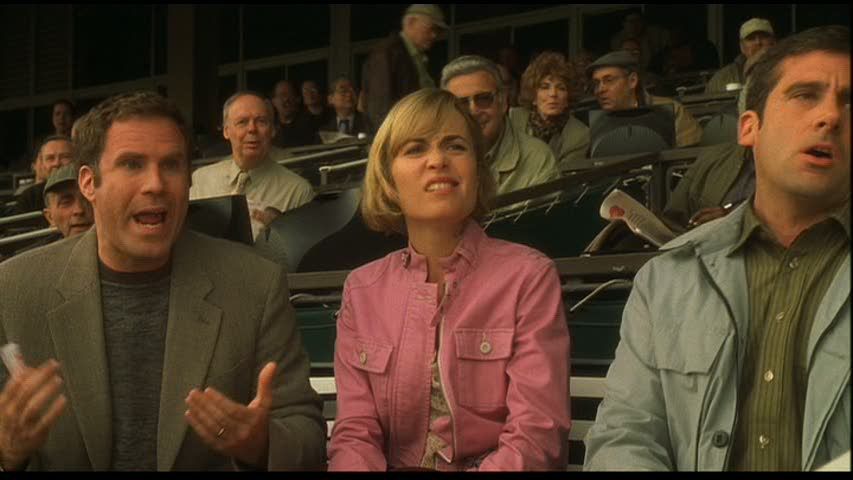

Instead, the supposedly "comic" story plays out like a light, fluffy tale of continually obstructed love, when the unhappily married Hobie falls hard for his flighty, troubled new neighbor Melinda. One wonders why Woody would cast Ferrell, or the gifted, naturally funny Steve Carrell (in a bit part as Hobie's buddy) if neither actor really gets to do anything funny; Carrell in particular seems wasted, mostly just delivering a few platitudes about marriage and honesty. Ferrell gets a few stale Woody one-liners and lets even them die; it's as though everyone thinks they've been cast in the dramatic half of the film. Maybe that's the point — that the only difference between comedy and tragedy is the way the story ends — but surely the script could've found a better way to indicate this idea than draining a comedy of its humor.

Fortunately, the "tragic" material in the film is handled much more substantially and intelligently — and what, exactly, does that say about a director once known wholly for his comedy? Radha Mitchell isn't given much to do in the lighter version of the story, but as a tragic heroine she comes into her own. She invests her character with an entire language of gestures and poses, ways of moving her face and speaking, a fully developed body language that communicates this character's emotional essence with every slightest move. It's a truly remarkable performance. It becomes hard to tell if Woody's writing is really that strong, or if Mitchell just brings out the hidden depths in this character so well that it wouldn't have mattered what Woody actually wrote for her. She's a shattered woman trying to regain some semblance of her life, some reason to want to live, and finding it, if only briefly, in a piano player with the unlikely name of Ellis Moonsong (Chiwetel Ejiofor).

Mitchell's every scene is quietly compelling, never overstating the naturally melodramatic emotions of her story. She has a restrained intensity that comes through especially in the scene where she tells Ellis about how she killed her unfaithful lover and got away with it. Her disheveled hair and black-ringed eyes, the way she smokes a cigarette with just the slightest tremor in her hands, her neurotic pacing and jittery mood swings: Mitchell builds this character from the smallest details up, creating a busy but always realistic performance that makes the tragedy of Melinda hit hard. Without her performance at its core, it's hard to imagine what Melinda and Melinda would be, but with her it's at least half a good movie, and even occasionally a great one. Mitchell, Sevigny and Ejiofor together craft the emotional foundations for a compelling drama in half the ordinary time for a feature film; the story is basic, even trite, but the quality of the acting fosters the necessary emotional investment in these characters. One feels their shifting attractions and breakdowns and self-justifications in the subtleties of their voices, the exchange of glances. Woody frequently frames the two actresses in tight closeups, allowing all the nuances of their performances to come through in their expressive faces: Sevigny's fluttering eyelashes and downward glances, a few tears gathering at the corners of her eyes; the hard lines of Mitchell's mouth and her flashing, fiery glare.

In short, this is a well-made drama wedded to a mediocre comedy. The film purports to establish a contrast between tragedy and comedy, but it actually provides an instructive example of the difference between vibrant, emotionally rich storytelling and bland storytelling that traffics in clichés. It hardly matters that the story in the film's tragic half is ugly and depressing, while its comedic half is light and, ultimately, happy; the former is viscerally engaging and the latter simply deadening. That in itself illustrates, better than anything else in the film, the message that Woody's shooting for here: it's not the story that matters, but the way it's told. He just probably didn't mean to get across his theme in quite that way.

5 comments:

This is one of my least favorite Allen films, and it's a shame because it's such a promising concept, an idea that Allen has often played with. Allen has obviously made comedies and tragedies and often talks about the differences between them, often attributing more weight to tragedy while acknowledging that comedy can be therapeutic. Crimes & Misdemeanors has tragedy and comedy resting comfortably side-by-side; Another Woman (which was really more drama than tragedy) was based on an idea that was originally intended as a comedy (and which he later re-used in Everyone Says I Love You). That plot is a good example of a story that can be explored two ways: in the drama, the overheard therapy session forces the main character to examine her own life. In the comedic version, Woody exploits the information for his own gain. Ironically, the Another Woman version ends more hopefully than its comedic counterpart. This is the kind of irony Woody is usually so good at. And yet he never exploits all these possibilities in Melinda and Melinda.

The main problem is that he picked such an uninteresting story to base the theme around. It's basically as simple as "A guy walks into a room..." Of course, that can end as tragedy or comedy. The guy could start juggling or he can pull out a gun and blow everyone's brains out. One wishes for a more specific incident to build this idea of tragedy/comedy around, and expects Woody to explore the meaning of both and how they play off each other. The story itself is so unspecific that it ends up being two vaguely similar movies, and as you said, the comedy is bland, and I don't think much of the tragic version either.

Interesting review of one of my favorites from Allen's later period, I think you touched upon a few things that I absolutely agree with. The first is the importance of Radha Mitchell; she is the glue that keeps the film together and I love her for it. The second is the quality of the tragic portion, which is, admittedly, much more effective than the comedy. However, I think that the comedy containing bits of tragedy (especially in the opening set up) is intentional and contrasts wonderfully with the minuscule comedic elements of the tragedy. To me it was as if Allen is saying that life is neither comic nor tragic, that it is inseparably bonded to both.

And I may be alone on this, but I liked Carrell. While he may be regarded as comic gold nowadays, I think he was put to good use in a relatively small but worthwhile role.

Woody essentially remade Another Woman twice - once as a complete comic/fun fantasy rewrite as "Alice" and then reusing the basis of the eavesdropping idea again in Everyone Says I Love You.

Woody has a good history with playing with telling the same story in different ways in a film, and, only a few years after Sweet & Lowdown (which has some key, funny and interesting scenes that are played out different ways based upon nothing more than which legend or myth you want to believe), you would think Woody might've been more interested in playing with that idea, to show the different ways any given scenario could play out. Or why he chose to tell Deconstructing Harry-esque episodic tales which he had flirted with in Husbands & Wives as well.

I think the root of it is in the fact Woody wanted drama to win - it's as if he set up this scenario so he could have a cinematic debate with himself to convince himself he wanted to do drama (which, aside from Scoop, that's essentially been the bulk of his work since). He admits as much in the Lax "Conversations..." book, saying he was far more interested in working on the dramatic half of the story and not nearly as interested in the comedic side, and it shows.

Good analysis. I agree that the tragedy is far more compelling. After reading this I went into my archives and found a rough-around-the-edges review I wrote at the time. A few observations from that …

“… the movie’s best scene is a touching moment when Ejiofor and Sevigny channel Paul Giamatti and Virginia Madsen in Sideways as Laurel and Ellis let their true feelings bubble to the surface in a quiet conversation at a dimly-lit restaurant. People in the acting business say that comedy is one of the hardest things to do, and I believe it. But the restaurant conversation is one of the few scenes in which we get swept up in one of the movie’s plot instead of its gimmick, so I tip my hat to the drama.

“Overall, the crux of the problem for Melinda & Melinda is that its tragedy isn’t very moving and its comedy isn’t all that funny. Some of Allen’s most celebrated movies, like Annie Hall and Manhattan, stand out because of his (at times) unparalleled ability to weave human stories from both tragic and comic threads. But this film’s separate-but-equal treatment leaves both narratives incomplete.”

I go on to suggest that Allen’s film is a lazy movie that never expands on its gimmick or even explores it with much intensity. Then I referenced the audition process for a season of Bravo’s now defunct movie-making reality series Project Greenlight: Rookie directors were given the same lines of dialogue without any kind of stage direction and were required to make a short film based on the dialogue. One of the finalists imagined a scene in a dentist’s chair while another finalist imagined an interrogation by chainsaw-wielding women … from the exact same dialogue!

I argued then (and now) that if Allen really wanted to impress he should have found a way to make the dialogue in both the comedy and tragedy at least mostly identical, thus relying on the staging of the scenes and the acting to alter the mood. That would have been impressive. This film is forgettable.

And though I agree that Mitchell is impressive in the tragic portion, her collective performance in this film was wildly over-praised upon its release. It was as if critics forgot that Mitchell was an actress and that playing two different characters in one film isn’t any more impressive than playing two different characters in two films.

Thanks for the comments, all. I think this film is especially disappointing because its premise is so promising -- as Tim points out, Woody was always doing stuff like this, playing with retelling the same story in different ways. So why does he seem so uninterested in really exploring the concept here? It seems like he really has lost his taste for pure comedy in recent years (though I'm almost alone in thinking that Scoop is actually quite good, if slight).

Jason, I agree that Mitchell has been overpraised for playing two different characters here -- hell, her character in the comedic half is barely even a character. But her performance in the tragic half is so impressive that I think she deserved the attention she got for it. Although, a quick perusal of her IMDB page doesn't reveal much else of note, a lot of romantic comedies and horror movies. You'd think a widely praised performance like this -- even in an otherwise mediocre film -- would've brought more substantial roles to her door.

Oh, and I agree about that scene between Ejiofor and Sevigny in the restaurant -- that's beautifully handled.

Post a Comment