Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is an absorbing, stylish character study, a film overflowing with complex emotions: love, loss, aging, friendship and betrayal, the confusions of political change, but most of all nostalgia, an aching, bittersweet nostalgia for a more innocent time that may never even have existed outside of the movies. Nevertheless, the film's titular Colonel Blimp — the nickname of Clive Candy (Roger Livesey), who matures during the film from a volatile young soldier into an aging, rotund, well-respected general — is indubitably a representative of that more innocent time. He is an embodiment of the English gentleman, with all that entails, for both good and bad. He is stiff and elitist, with a great respect for rules and procedures, for protocol. He's condescending and imperialist, unquestioning of his own country in all that they do. But he's also kind-hearted and generous, the kind of man who will fight a duel and then become best friends with his opponent afterward.

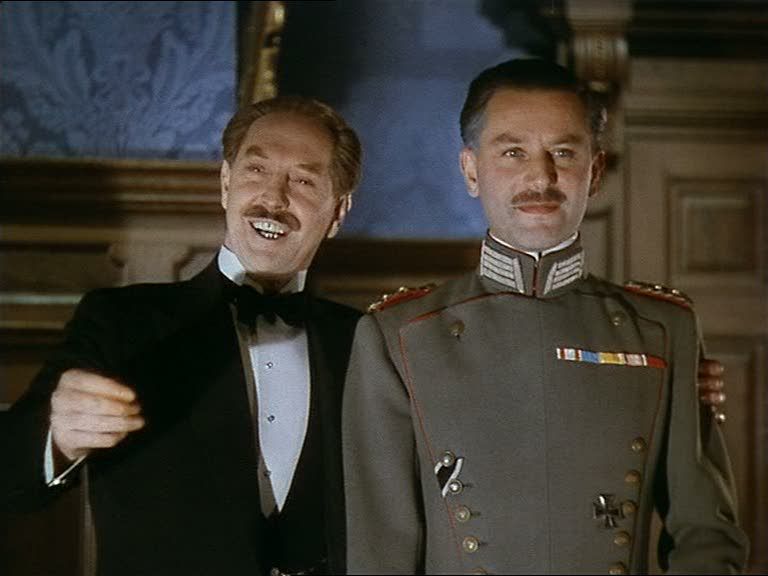

This is exactly what happens in the film's first extended segment, a reminiscence of Candy's time in Berlin during the early 1900s, where he has gone to defend his country's honor over accusations that the British had committed atrocities during the Boer War (which, of course, they did, though Candy doesn't know this and the film is politically unable to acknowledge it). Candy means well, but his blundering nearly causes an international incident when he, more or less inadvertently, insults the entire German army. The Germans pick an officer from their ranks to fight a duel against Candy, and when the two men wound each other, they are sent to the same hospital to recuperate. There, Candy becomes fast friends with the officer, Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook), despite the other man's lack of English. They communicate mostly through the lovely English governess Edith Hunter (Deborah Kerr), who in the process falls in love with Theo. This is the film's most detailed and evocative segment, and for good reason, since the events here will haunt the remainder of Candy's long life. His friendship with Theo will last, despite long absences when the two men do not see each other, and despite even the period of hostility when they fight on different sides during World War I. But Candy will be even more deeply scarred by his unrequited and, indeed, never pursued love for Edith, who stays behind in Berlin to marry Theo. Candy, always a gentleman, smiles broadly and congratulates his friend when he learns of the couple's engagement, but he is hurt nonetheless, and he returns to London feeling a great loss, a loss that will affect him for the rest of his life. He will continue looking for Edith everywhere he goes, and will find at least two more incarnations of her (both also played by Kerr).

This romantic, melancholy story is simply one thread weaving through Candy's long and eventful life. In between incidents, the film uses documents and objects to mark the passage of time: newspaper reports, photographs, letters, and especially the accumulation of animal heads in Candy's den, each one dated and stamped with the location where he shot it. Various deaths are noted in simple two-line obituaries, the entirety of a life reduced to a platitude in a newspaper — the exact opposite of this film's sprawling, generous storytelling. Even so, these interludes sometimes seem to elide too much. Candy's long and presumably happy marriage to Edith look-alike Barbara Wynne (Kerr again) is treated very superficially, and his wife's character is never allowed to develop very much beyond her resemblance to his first wife. One wonders if this is intentional, reflecting Candy's essential disinterest in her beyond her appearance. One gets this sense especially from a late scene, after her death, in which the much older Candy proudly shows off her portrait to Theo, mechanically repeating how much she looked like Edith.

In a way, though, it hardly matters, since despite the romance the real central relationship of the film is the one between Candy and Theo, who reconnect as old soldiers when the latter flees to England, escaping from the Nazi horrors in his own country. The relationship between these two men is complex, woven together with politics and with their mutual love for the same woman. One of the film's most interesting uses of time is the way it condenses the period of time between the two World Wars, so that Theo's departure from London as a defeated P.O.W. after World War I is swiftly followed by his return to London many years later as a refugee from the Nazis. In the first scene, he leaves offended by Candy's patronizing attitude towards him, and he angrily tells his fellow German soldiers about the weakness and naivete of Britain — an ominous suggestion of the post-WWI bitterness and bad feelings that would thrust the Nazis into power. By leaping over the intervening years, the film powerfully depicts how Theo's initial bitterness over losing the war had given way to a more resigned melancholy, as well as a hatred of the evil forces taking control within his own country.

This film was made at the height of World War II, so it should be no surprise that it contains elements of anti-German war propaganda. What's interesting is how subtly this material is incorporated into the narrative, and how sophisticated and twisty the film's messages about war and nationalism can be. Candy is a naïve figure, convinced of his own rightness and that of his country: he believes in fighting wars according to rules, maintaining strict decorum and gentlemanly conduct even in the midst of combat. A repeated theme throughout the film is Candy's obliviousness, his outdated outlook on the world, which persists even as those around him increasingly argue that they must respond to the aggressions of their enemies not as gentlemen but as unrestricted fighters who will do anything to win. One of the film's most interesting questions, then, is whether it's Candy or the filmmakers who are actually naïve — or if they just expect audiences to be naïve. The film repeatedly characterizes British fighting methods as decent and noble and pure while the methods of their enemies are characterized as dirty and cowardly. Beyond the obvious contradiction — the quaint fantasy of fighting a "decent war," as though so much bloodshed could ever be anything but horrible — this mentality willfully glosses over all sorts of historical facts about British warfare preceding World War I, which could hardly always be described as "noble."

Candy doesn't realize that his ideal of a gentleman's war is a fantasy. There are hints in the film of darker realities — one scene cuts away before a scarred soldier begins interrogating a group of German prisoners, but there's little doubt that things got ugly after the fade to black — but it's obvious that there couldn't be any more tacit acknowledgment of these kinds of things, not in a wartime propaganda drama. For the most part, this is a brightly colored Technicolor fantasia of Candy's worldview, nostalgic for a time when wars could be fought with honor. But as nostalgia goes, this is especially sumptuous and skillfully executed nostalgia, with gorgeous studio-bound Technicolor imagery, lushly painted matte backdrops standing in for sunsets and bombed-out wartime locales. The obvious artificiality of it all helps create the impression of war as a clean, honorable affair, a game between gentlemen, who set start and end times, in between which they bomb one another. The beautiful, textural cinematography (by George Périnal, with future Powell/Pressburger cinematographer Jack Cardiff assisting) is suited equally to sweeping, colorful vistas and enveloping closeups.

One of the best of these is an extended shot of Theo as a much older man, a long, carefully held closeup during which he tearfully recounts the story of his stay at the hospital in Berlin, where he met both his future wife and the friend who would remain his one constant throughout his life. The camera stoically studies his face, now lined and worn with age, his features softened by his bittersweet memories of the past, of this time when he was so happy. The rich emotions of this scene are deepened by the immersive quality of the closeup, and by the fact that these characters have grown and matured over the course of the film, aging slowly into their older incarnations. The makeup used to age them sometimes makes them look mummified, caked in white paint, but the subtlety and warmth of the performances always shine through. Candy could easily have been the oversized caricature implied by the film's title, a walking symbol of British obliviousness and elitist condescension. And he is, to some extent. But he's also a sympathetic, richly drawn character, a man left behind by history, a man whose private ideals are increasingly out of sync with both his nation and the world, if they were ever in sync with anything beyond his own fantasies to begin with.

10 comments:

All well said, but not a mention of David Low? Clive Candy is The Archers' baby, but he could not have existed without Low's cartoons, which portray the Colonel as a more irredeemable reactionary than Candy. But despite softening Blimp's image, Powell & Pressburger were still accused, if I recall correctly, of slandering Britain. Sometimes you just can't win.

The Lasting Tribute website has updated its memorial pages to include Jack Cardiff.

http://www.lastingtribute.co.uk/tribute/cardiff/3066170

It's a respectful memorial to Jack and somewhere to pay tribute to the family's fortitude at this difficult time.

EVERY comment is monitored so that nothing offensive or inappropriate is published.

Good point, Samuel. I'm aware of the Low cartoons but not really familiar with them. And yes, this film apparently had a lot of difficulty even getting made because certain forces in the government (Winston Churchill especially) saw it as a slander on Britain released at the height of wartime.

Patrick, thanks for the info on the Cardiff memorial. He was one of the greats; even if he'd never shot anything but Black Narcissus it would've been enough.

I am at school now, but I can't wait to return home later this afternoon to read (and comment on) what appears to be yet another glorious, definitive treatment of one of the great works of British (and world) cinema. True, Cardiff only assisted here, but it's altogether fitting that this review is posted at the time of his passing, as his mark is evident in the color and textures.

Without going into too much detail as I am pressed for time, Blimp is the greatest British filmf of all time and, for me, the greatest films of the 1940s. Period. Cardiff was Périnal's apprentice, for sure, but he was as integral to its visual sheen as John Alcott would be on 2001 in assisting Geoffrey Unsworth. In both cases, they became the director's DP of choice.

David Low's Colonel Blimp was an entirely negative figure, and I suspect that the Archers' film met resistance because people like Churchill assumed that it would be a more faithful representation of the cartoon Blimp than it proved to be. Low often portrayed Blimp pontificating in a steambath, which is why Powell and Pressburger introduce the elderly Clive Candy in one. I ought to add my respects to Jack Cardiff for shooting some of the most beautiful films ever made.

Magnificent review of a film that many consider the masterpiece of the P's, and one that fully does the film justice. You actually summarize it's themes and concerns in your opening sentences:

"Colonel Blimp is an absorbing, stylish character study, a film overflowing with complex emotions: love, loss, aging, friendship and betrayal, the confusions of political change, but most of all nostalgia, an aching, bittersweet nostalgia for a more innocent time that may never even have existed outside of the movies."

This of course flies in the face of those who view the film and believe it's about 'patriotism.' Ironically, it's central friendship thumbs its nose at the Churchill claque, who subsequently would find the relationship as an affront to Old Glory.

One of Ed's most brilliant observations here is this one in describing Theo in the hospital later on:

"The camera stoically studies his face, now lined and worn with age, his features softened by his bittersweet memories of the past, of this time when he was so happy. The rich emotions of this scene are deepened by the immersive quality of the closeup, and by the fact that these characters have grown and matured over the course of the film, aging slowly into their older incarnations."

This review rightly talks of the excellent stylistic devices to convey the passing of time, the great performance given by Roger Livesay, the romantic, melancholy fabric, the expectant anti-German propaganda, and of course essentially, in Ed's words, this:

"The beautiful, textural cinematography (by George Périnal, with future Powell/Pressburger cinematographer Jack Cardiff assisting) is suited equally to sweeping, colorful vistas and enveloping closeups."

Cardiff's greatest work ever, methinks is his incomparably beautiful and breaktaking BLACK NARCISSUS, but certainly his complicity here in this very great film is most evident.

Another excellent review of a film I like a lot. There's something ineffably strange about Powell & Pressburger films, about their storytelling, their mood & tone, their particular brand of flamboyance. I can't put my finger on it exactly but there's the impression that the filmmakers aren't even aware of how strange and offbeat their vision is, that they are as innocent in this regard as Clive Candy himself, which lends their films an extra dimension of charm (of course I don't think this ignorance actually existed, but for whatever reasons the films still suggest it, and are all the better for doing so).

By the way, is it just me, or does Pressburger seem to be getting more of the credit for these works than he used to? When Powell had a resurgence in popularity before his death, based largely on Scorsese's celebration and the re-evaluation of his solo work Peeping Tom, it seems like he was celebrated as an auteur, who generously shared credit with Pressburger but was primarily responsible for the vision onscreen. Now, in blogs and Criterion press release, we're back to hearing about "Powell & Pressburger." Interesting, and I wonder what's behind the switch (which is probably deserved).

Thanks for the comments all. Sam, I agree about the beauty of Black Narcissus. Cardiff was brilliant with colors.

MovieMan, I have a very similar reaction to the P&P films, which seem to have this ineffable strangeness about them. They're unlike anything else. And personally, I've always wondered just what the working relationship between them was, whether Powell (as the more experienced director) mostly handled the visual components, or if it was more of a true collaborative work. I don't know nearly enough about their body of work to make even an educated guess, but since they're credited together, I'll assume Pressburger deserves his share of the credit.

I vaguely recall hearing that Pressburger largely handled scriptwriting duties, while Powell focused on the direction, but that he was so enamored of Pressburger's contribution to the vision that he co-credited him. I'm not sure this is true, or if it stems from the auteurist Powell reading but either we they definitely both contributed greatly to their films' ineffably unique vision. None of these stories unfold or work the way screenplays are supposed to - the narrative momentum seems to move laterally, if that makes sense - yet they succeed.

Post a Comment