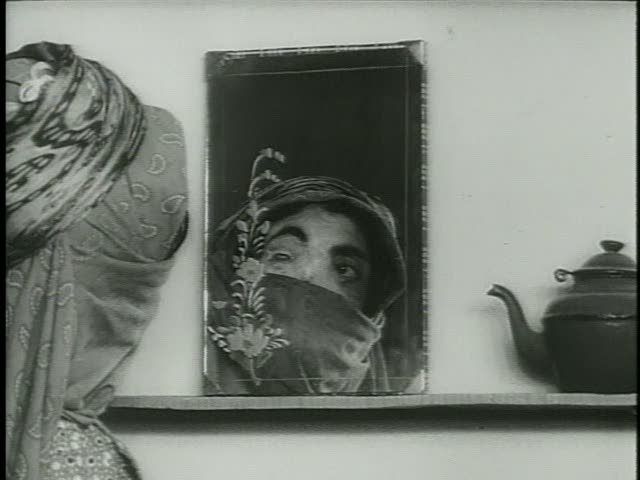

Forugh Farrokhzad's The House Is Black is a harrowing, horrifying, artfully made documentary, the only film made by the Iranian poet Farrokhzad. Her subject here is leprosy, and she looks directly, unflinchingly, at the devastation caused to the human body by this disease. She does not look away, not from the worst deformations this disease creates. Her purpose was to expose the cruel and unnecessary way that lepers continued to be treated in Iran, herded into isolated leper colonies where their disease went untreated, causing them to slowly and painfully disintegrate. Farrokhzad's film was intended to raise awareness about these conditions, and to stress that this situation need not be. A male narrator dispassionately lists facts about leprosy while Farrokhzad cuts quickly and abruptly between some of the most horrifying images of the disease's effect: limbs that seem to have been worn away, as though by erosion; noses caved in, creating crater-like gaps in the patients' faces; skin that flakes off, scraped away by a doctor's instrument. And yet the narrator says: "leprosy is not an incurable disease." He says it twice, once at the beginning and again at the end of this montage, repeating it to make sure that the meaning of his words is not lost. These people, suffering so greatly, could be cured. The unspoken implication is that their country, their government and their social structures and their medical system, have failed them. They could be cured, if only someone was willing to take the initiative to cure them, rather than herding them into isolation to prevent the spread of the disease and then forgetting about them.

There are two narrators in the film, the first the male narrator mentioned above, who appears sporadically to deliver straight facts in an objective tone. The second narrator is Farrokhzad herself, who delivers a lilting, poetic, religiously tinged voiceover. One of the most subversive undercurrents in the film is its subtle criticism of Islam, and religion in general, for failing to take a more compassionate and helpful interest in these forgotten and suffering people. Farrokhzad continually shows the lepers praying and giving thanks to God, and she purposefully contrasts their faith and devotion against the abjection of their condition. Again, her method is not to state her ideas directly, but to generate tension between a seemingly straightforward voiceover narration and the bracing power of the images she pairs with these texts.

In this way, she calls attention to the irony of the lepers' religious devotion, their continued praise of God even as they needlessly suffer and rot away. One man, leading the prayers, holds up his arms, which have been reduced to twisted and skeletal stumps, and prays to God with words that include "my two hands," hands he no longer has because of his disease. Other lepers unironically thank God for giving them both a father and a mother, even though most of them are here without families. There's a heartbreaking scene in a schoolhouse where a school teacher asks one of his pupils why they should thank God for giving them a father and a mother. "I don't know," the boy responds, "I have neither." There's something about this scene that makes it seem staged — it's too pat, too perfectly suited for the messages Farrokhzad wants to send — but it is a devastating critique of religion anyway. Why, Farrokhzad asks, do these people worship a God who has seemingly abandoned them? Why do they thank God for blessings that he has not bestowed on them? It is as though their religious fervor is abstracted from the actual conditions of their lives, as though they are hardly even thinking about the words they're saying.

Farrokhzad, though, is particularly attuned to the meanings of words. She was a poet, after all, and thus very sensitive to words and the disjunctions between language and reality. As a filmmaker, however, her skills are hardly just verbal. Her visual sensibility is relatively straightforward on the surface, and yet she creates rather complex effects with editing and the relationships between the soundtrack and the images. The House Is Black is entirely the product of her sole sensibility in a way that few films are: she not only wrote and directed the film but, crucially, edited it herself as well. Her editing is crisp and deliberate, and she frequently returns to images that have appeared already, inserting them into rapidly paced montages where their meaning is changed or intensified by the images around them or the content of the voiceover.

Two of the most poignant segments in the film are two sequences where Farrokhzad focuses on the ways in which life in the leper colony mirrors life in the outside world. The first is a montage of women prepping themselves, combing their hair or rubbing kohl around their eyes, making themselves "beautiful." It's a moving sequence, an indication of how these people, shut off from the rest of the world by their disease, attempt to retain some connection to their previous lives — and to the concepts of "beauty" and "ugliness" as defined by society. In another scene, Farrokhzad shows a group of children playing with a ball, all of them laughing and cheering, jockeying for position in the game they're playing, having fun, oblivious to the sores and deformities scarring their bodies. In their smiles and their body language, they look like any other children, cheerful and carefree as kids are supposed to be. But their distorted faces are hard to ignore, and Farrokhzad immediately cuts from this scene to images of older lepers, crippled and badly deformed, as though suggesting that these happy children will grow up into misery if their condition is not treated.

The House Is Black is a powerful, unforgettable film, a documentary whose forthright and unblinking look at life in a leper colony casts light on the suffering of people living in darkness, away from society's attention. Farrokhzad does not allow society to forget the lepers, does not allow her audience to look away or to take pity without also taking action. Her film does not merely wallow in suffering but calls for something to be done about it.

5 comments:

A magnificent review of what you rightly intone is "a powerful, unforgettable film." You have captured its essence, and have (like the film) unflinchingly focused on Farrokhzad's obvious disdain with religion, which like the social structures here, have deserted them. I love your description of Farrokzad's "lilting, poetic narration, which informs here real artistic slant in life as Iran's pre-eminent poet of the twentieth century (she was sadly killed shortly after making this film at a very young age in a car accident) but you magnificently relate her crossover talent here in one of this superb review's finest passages:

"Farrokhzad, though, is particularly attuned to the meanings of words. She was a poet, after all, and thus very sensitive to words and the disjunctions between language and reality. As a filmmaker, however, her skills are hardly just verbal. Her visual sensibility is relatively straightforward on the surface, and yet she creates rather complex effects with editing and the relationships between the soundtrack and the images. The House Is Black is entirely the product of her sole sensibility in a way that few films are: she not only wrote and directed the film but, crucially, edited it herself as well. Her editing is crisp and deliberate, and she frequently returns to images that have appeared already, inserting them into rapidly paced montages where their meaning is changed or intensified by the images around them or the content of the voiceover."

There was tension between the Forrokhzads and organized Islam, which later resulted in her famous political activist brother's behaeding in the U.K., as a result of his complicity in criticizing the Khomeini regime.

In any case, this 22 minute film is as searing and heartfelt a testament to to suffering humanity as we've ever seen in the cinema, and it's worthy of the masterpiece label.

This film is underexposed because of obscur copyright and political censorship issues... But now it's viewable online at UBU!

If you admire this film, you should definitely check out Jean-Daniel Pollet's "L'Ordre".

Sam, it's definitely a shame that Farrokhzad's life was cut short; one can only imagine what else she might have accomplished in film. This short reveals a very interesting and idiosyncratic cinematic sensibility.

Harry, thanks for the link, hopefully more people will be able to check out this stunning film that way.

This is top stuff... I Love the film. But, but, but couldn't give full marks to it because it is closer to poetry than cinema. I believe cinema should imitate poetry only in as much as the ecstatic ambiguity is concerned. The leaf floating in the water, the silhouette of the man walking back at twilight etc. were trademark poetry.

@Harry: It's awesome what UBU is doing, Jack Smith, Hollis Frampton, Dziga Vertov Group films and now this... Cinema is saved!

Oops! I might have given the impression that I do not consider it good. It is masterfully done.... well, almost. Top notch review, goes without saying.

Great review!

We're (once again) linking to your review for Iranian New Wave Wednesday at SeminalCinemaOutfit.com

I'm sure we'll be back!

Post a Comment