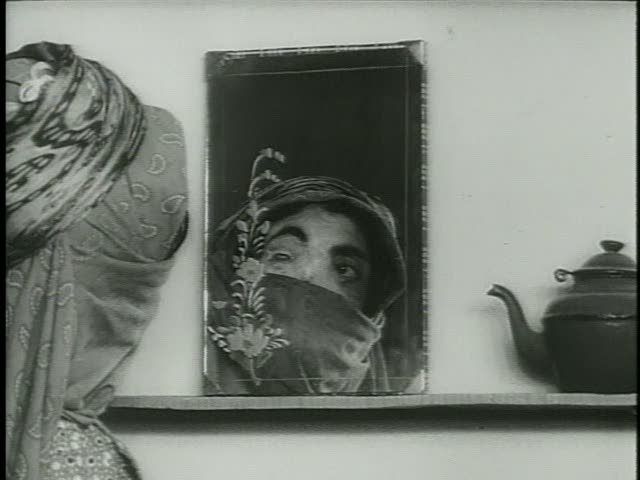

Alain Resnais' Muriel ou Le temps du'un retour is a curiously unsettled, and unsettling, film, a continuation of the disjunctive, ambiguous dream logic of Resnais' previous feature, Last Year At Marienbad. Like the infamously unresolved Marienbad, Muriel revolves around missed connections, complicated pasts, lies and disguises, shifting identities, love affairs and betrayals. Also like its predecessor, it mocks conventional storytelling by shattering narrative into a patchwork series of disconnected events, using editing to thrust seemingly unconnected moments together. In the opening minutes of the film, Resnais' editing confounds a prosaic conversation by chopping up the scene into miniature details: bowls of fruit, a doorknob, a piece of furniture, a door, anything but the people actually speaking. This opening suggests the destabilization to come, but only partially. A few minutes later, a nighttime scene is interrupted by a series of shots of urban streets, shifting unpredictably back and forth from night to day. Resnais is mocking the convention of the establishing shot, mocking the whole idea of setting the scene through images of scenery: the only thing these shots establish is that time slips unpredictably, that location is unstable, that this is a film where the sense of reality can be disrupted at will, images thrown together without logic, randomly, so that an ordinary story becomes surreal and abstract.

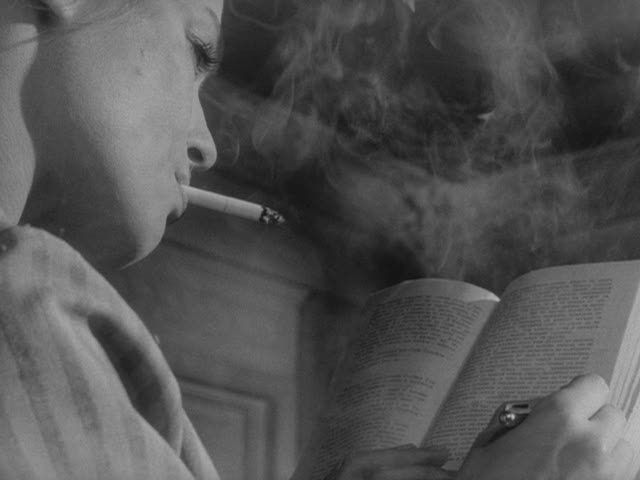

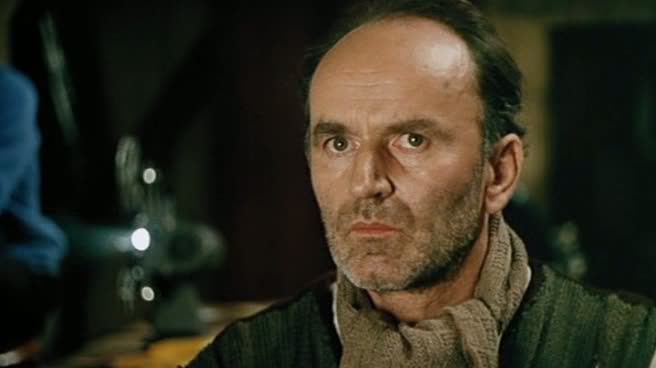

And beneath it all, this is an ordinary story. As Hélène (Delphine Seyrig) says at one point, speaking of her own long-ago love affair with Alphonse (Jean-Pierre Kérien), "It's a banal story. I find that reassuring." That's not quite right, though. For one thing, Resnais isn't telling a banal story: he's telling several, all of them blended together, their facts and details mixed up and prone to change at a moment's notice. For another thing, the way in which Resnais tells this story is anything but reassuring. It's the story of a woman trying to reconnect with the lover who left her many years before, when they split apart towards the end of World War II. Alphonse comes to see his old lover Hélène, at her invitation, bringing along a woman who he calls his niece, François (Nita Klein), but who is really (maybe?) another girlfriend, perhaps one of many for this deceitful man. Alphonse stays with Hélène, perhaps for many months, perhaps for just a few days — it's hard to tell, as Resnais chops up the story into disconnected moments that seem to mean nothing in isolation, the sense of time utterly obliterated by these fragmentary montages of snatches of dialogue, silent temps mort interludes, puzzling diversions.

In any event, the story seems to be locked into a never-ending stasis, trapped in cycles of repetition like the frustrated maybe-lovers of Marienbad. Alphonse is always threatening to leave, and so is François, but neither ever does despite many conversations that seem to end with the matter resolved, with one or the other ready to depart immediately. Hélène's stepson Bernard (Jean-Baptiste Thiérrée), newly returned from the war in Algeria and obviously mentally scarred by the experience, is similarly always in the process moving out, but never seems to finish. He periodically packs up his stuff and gets into arguments with Hélène, but then in the next scene he might be back, magically reappearing from one shot to the next as though nothing had happened. At one point, Hélène says that Bernard has been gone for eight months, but could that really be true? The film's manic disregard for time and space makes it impossible to tell.

It's as though these characters are trapped by this story, as trapped as the partying bourgeois of Buñuel's The Exterminating Angel, made the year before. Buñuel trapped his characters in a physical space, but Resnais encircles these people only with the boundaries of narrative and cliché. They're hemmed in by the story, by the editing, by the illogic of a film where everything seems to be perpetually on the verge of happening without ever quite getting there. The characters keep expressing their emotions, telling and retelling their stories, exploring a past that seems to be evasive and contradictory, but they never progress beyond their state of stasis, repeating the same actions and the same arguments over and over again.

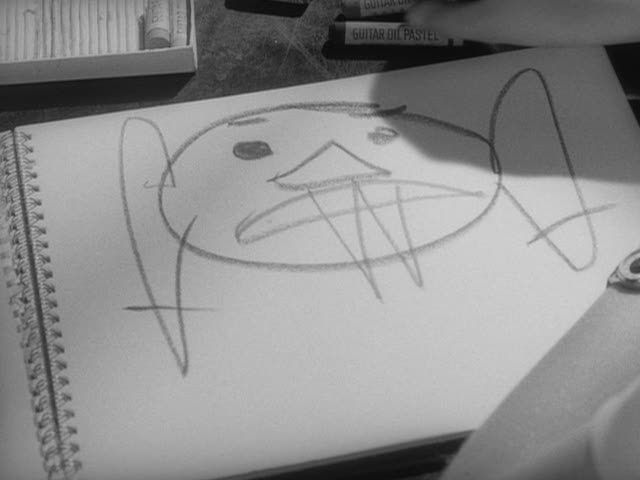

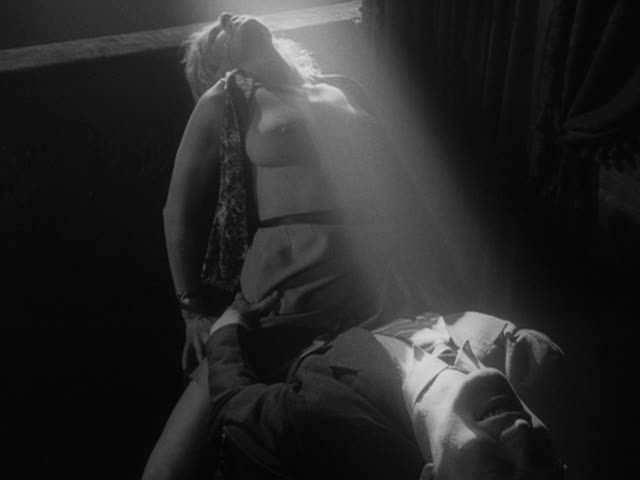

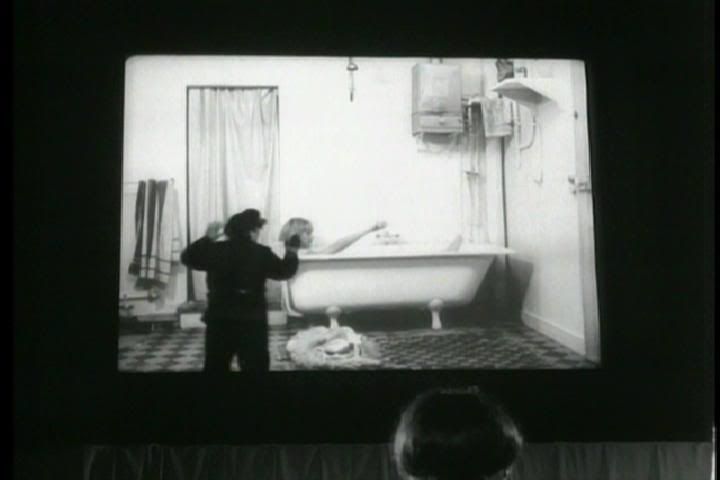

The key to all this confusion lies in the film's subtext, its hints of wartime trauma and atrocity. Bernard says he has a fiancée named Muriel, who no one has ever met, and he's always saying that he's going off to meet her. In fact, no such girl exists, even though Bernard does have a girlfriend (Martine Vatel), whose name turns out to be Marie-Dominique, not Muriel. The secret of Muriel is revealed during a sequence in which Bernard, an amateur filmmaker, provides voiceover narration over a reel of grainy, scratchy clips of soldiers. His story initially seems like a romance, like the story of how he met his girlfriend Muriel: he saw her from across an office, he went over to see her, there were typewriters, and then instead of an office it's a courtyard, and then it's a warehouse. Without warning the story has become a war story, a story of soldiers torturing and raping a prisoner named Muriel, stripping her naked, burning her with cigarettes, kicking her as she lays on the ground dying. It becomes clear that Bernard saw this during the war, that he even participated in the abuse, although perhaps not as enthusiastically as some of the others. This is the girl he's obsessed with, the girl who occupies his thoughts now, not a lover but a symbol for the horrors of the war, a symbol of the brutality inflicted by soldiers on those they oppress, a symbol for the French occupation of Algeria and the terrible effect of this war on both those fought it and those who suffered innocently under its toll. When Bernard says he's going to see Muriel, where does he goes? What does he mean? Is it that he sees her everywhere now?

The Algerian situation haunts the film, and so does World War II, the occupation of France, the Liberation. Boulogne, the town where all these memories and stories coexist, was bombed badly during the war, and was largely rebuilt. The characters speak of places that no longer exist, places that have been reconfigured: Hélène's apartment, she says, occupies the same physical place that once housed the attic of her friend Roland's (Claude Sainval) childhood home. This is why the characters, weighted down by the past and by geography, can't escape their cycles of disconnection and dishonesty, can't help but repeat the stories of the past.

For Resnais, this cyclical trap is rooted as much in things as in people. Hélène is an antique dealer, working out of her apartment, and as a result she lives, quite literally, amidst the clutter of the past — as Bernard says near the beginning of the film, one never knows what era one is in in a place like this, where the styles of the past clash against one another, multiple times coexisting in the same place. In much the same way, history — World War II, Algeria, bombings and atrocities — coexists with the present, never quite fading away. The records of photographs and audio recordings, like those that Bernard preserves, can be reminders, evidence, but they can also lie: Alphonse, who has never been to Algeria, pretends he has and presents photographs as proof. He's a tourist, like the soldiers of Godard's Les Carabiniers, insisting that snapshots can stand in for reality, that a photogenic image can paper over the real oppression of the Algerian people. Alphonse is also a bigot, a man who says he respects all races, "even the Arabs," a phrase in which the "even" tellingly reveals his real feelings, barely covered by his false civility.

Muriel is a remarkable film, a surreal subversion of bourgeois narrative, in which the unstably shifting tectonic plates of place and time create a very uneasy footing for these characters. Even the music — a spiky, dramatic score by Hans Werner Henze, with operatic vocals by Rita Streich — contributes to the instability, as the music appears sporadically and unpredictably as an accent, except that it doesn't seem to be accenting anything in particular. The music suggests suspense and action while the characters never do or say anything beyond banalities, beyond the rote repetition of their familiar cycles. The very form of Resnais' film mocks these bourgeois fakers, mocks their petty aspirations and desires, mocks the way they focus on the trivialities of their personal histories while ignoring the bigger picture. For Hélène and Alphonse, self-involved, wrapped up in their own dramas, World War II was a backdrop for their aborted love affair, but Resnais doesn't allow them to leave it at that, as complicated political contexts keep encroaching on their hermetic little melodramas.