Throughout his career, Jacques Rivette has always flirted with the thriller genre, evincing a fascination with the shadowy conspiracies and labyrinthine plots that twist and turn behind the scenes, their contours hidden, their surprises held back. In spite of this, Rivette's cinema has been in many other ways the antithesis of the thriller, trading in slow, languid character development and a patient exploration of the truths and lies shared between his characters. He continually adapts the framework of the genre picture — the thriller, the mystery, the detective film — to his own set of concerns and his own unique perspective. In Secret Défense, perhaps for the first time, he confronts the thriller on its own terms, crafting a masterful mystery plot in which, nevertheless, the emphasis is on the longueurs between actions rather than on the twists and turns of the plot.

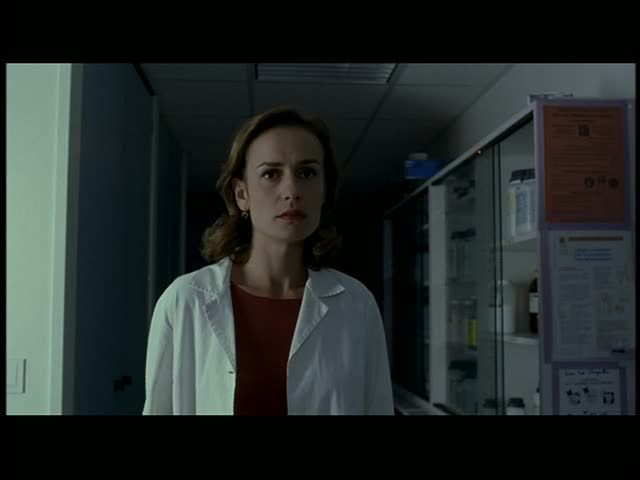

The story is certainly an archetypal revenge scenario. Sylvie (Sandrine Bonnaire), a research scientist, learns from her brother Paul (Grégoire Colin) that their father, who had died five years before in a train accident, had not fallen off the train but had in fact been pushed. Paul suspects their father's business partner Walser (Jerzy Radziwilowicz), who now runs the business in his place. Sylvie is not so sure, but she fears that her brother will rashly and foolishly try to kill him, so to cut him off she goes to kill Walser herself instead. This triggers a convoluted sequence of events in which Sylvie is placed in the same situation as her hated nemesis, coming to understand Walser and why he did what he did. The film doesn't lack for drama, but that's not what primarily interests Rivette. The most crucial narrative scenes have a kind of blunt, clipped quality, as though Rivette is only fulfilling an obligation by showing us these things. Violence happens quickly and abruptly, with a faint undertone of surrealist absurdity, and also a touch of Rivette's theatricality: these are stage deaths, the gestures just slightly exaggerated and stylized.

Rivette intersperses the dramatic scenes, the confrontations and revelations and twists, with extended sequences that expose the mechanics by which the characters get around, communicate with one another, navigate their world and their story. The scenes that would be brief and obligatory in another film, Rivette expands and elevates to a central importance. The simple act of moving from one place to another is never glossed over, but is instead transformed into an epic narrative in itself. At one crucial moment, after she has decided to kill Walser, Sylvie must take a long journey from Paris to the countryside, where Walser is spending the night at his palatial home. Another film would cut from Sylvie's decisive action of packing for the trip directly to her standing in the dark outside his home, stalking him. Instead, Rivette follows her in near-silence as she buys her train ticket, switches from train to train, nervously fidgets, tries on different pairs of sunglasses as though fancying herself a character in a gangster movie. He follows her long walk through the dark dirt roads leading from the train station to Walser's house, as she hides her face from passing cars and strides purposefully towards her fatal destination. Rivette lingers with her, refusing to resort to an easy linkage between decision and action: he emphasizes the time she has to think, to ponder what she's going to do, to wonder what it's going to be like when she finally gets there. And then, when the moment finally comes after all this anticipation, nothing goes as planned, and it's over in a startling few seconds, a brilliant climax/anticlimax before Rivette fades to black.

Rivette is fascinated with the long pauses between actions, the moments of stasis where Sylvie is simply lounging around her apartment — with Mark Rothko prints propped up casually against the walls — or working at her lab or traveling by train. At times, Rivette seems intent on remaking, again and again, the Lumière brothers' L'arrivée d'un train à La Ciotat, and imagining its sequels and prequels: woman waiting for train, woman traveling on train, woman switching trains. And yet Rivette's film is irrevocably set in an era when such things no longer hold the fascination they did for audiences in earlier times. Travel like this is mundane, ordinary, and Rivette's lengthy shots of trains pulling in and out of stations capture this prosaic quality without obscuring the strange beauty the Lumières must have seen in such images.

The train is no longer the height of technology, and Rivette continually reminds us of this by packing the film with then-modern accoutrements: cordless phones, answering machines, fax machines, computers, the scientific equipment that Sylvie uses in her lab, and the mysterious weapons systems being manufactured by Walser's company. These technological devices drive the plot, but often in negative ways: the phone bears only bad news, and more often than not the answering machine's assurances that someone will "call back" are never fulfilled. Communication is difficult, missed opportunities are frequent, and thus everybody seems to be out of sync with everyone else, misunderstanding one another's motives and actions and words. All of this technology is amassed around these characters to facilitate things, to make travel and communication easier, but they are nevertheless unable to make connections or speak openly to one another, to get beyond the lies and silences. This is why the truth comes out only slowly, hesitantly, after false starts and misleading diversions. It's Rivette's take on the necessity for deceit and double talk in the thriller genre: the characters lie because they simply don't know how to talk to one another. This is also why, perhaps, Sylvie keeps dodging her earnest, likable boyfriend Jules (Mark Saporta), unable to say anything to him. Later, she'll manage to tell a friend the truth only by backing into it, telling it first as though it was part of a dream.

Rivette's characters are so often weighted down by their histories, haunted by the past — sometimes literally, as in the romantic ghost story History of Marie and Julien. Here, Sylvie is haunted by the long-ago death of her older sister Elizabeth, a suicide she never understood, a death that lingers with her just as Paul can't get over their father's death. This obsession with missing relatives extends outside of Sylvie and Paul's family with the entry of the waifish Ludivine (Laure Marsac), who's searching for her missing sister Véronique (also played, earlier in the film, by Marsac, in a chameleonic double role: the pale, severe Ludivine and the lively Véronique couldn't be more different). Rivette has always been fascinated by doubles and mirroring, a theme that was especially apparent in the Duelle/Noroît diptych of 1976. Here, multiple characters enact the same plot, as though trapped within an endless cycle, unconsciously repeating the same narratives: investigation, mistaken assumptions, murder. Murderer and victim switch places and identities fluidly, standing in for one another and for others — some kill so that others don't have to, some die so that others won't have to. It is a cycle of sacrifice, a cycle in which the deeds of the past reverberate in unexpected ways in the present.

This has often been a key theme for Rivette, for whom revenge and violence hold a peculiar fascination — for a director renowned for his slow, stately pacing, his films seethe with strong emotions just below the surface. This one is no exception despite its stony, tranquil surface. Rivette gets understated performances from his cast, who don't react with melodramatic verve to the sometimes startling turns of the plot. If the narrative edges into soap opera in its final act, it's barely noticeable because the characters take it all in stride, with little to betray their tangled inner states. Bonnaire especially is perfectly balanced, capturing Sylvie's increasingly frazzled nerves and disintegrating composure while hardly ever venturing outside of a very narrow range of calm, non-committal expressions. Rivette's camera often lingers over the actress' face, so distinctive and angular, staring into her eyes or tracing her geometric profile for long moments of quiet contemplation.

Besides the oblique references to Rivette's past in terms of theme, this film seems like something of a summation for the director, a conscious engagement with the past. Just as the past and its horrors haunt these characters, the film itself is populated by ghosts from Rivette's cinematic history: his one-time youthful heroine Hermine Karagheuz (of Duelle and Merry-Go-Round) has a cameo as a stern, sour nurse; Sylvie's mother Geneviève is played by Out 1's François Fabian; Bernadette Giraud, who played a young aspiring actress in Gang of Four, reappears here as a maid. Rivette has often used the same actors multiple times, but here the way he inserts these characters around the fringes of the narrative seems calculated to call attention to the device, to add a metafictional layer to the casting. The appearance of these characters, particularly the instantly recognizable Karagheuz, is a way of tying this film to its director's lineage: this isn't just a thriller but a Rivette thriller. And that means it's a particularly smart, contemplative and entrancing thriller.

No comments:

Post a Comment