François Truffaut had, from his very first feature, his famous debut The 400 Blows, been very interested in childhood and the experiences of a child in a world governed by adult rules. The director's 1970 film The Wild Child returns to that theme and to the territory of childhood, albeit from a very different angle. Based on a true story, the film deals with a young feral boy (Jeanne-Pierre Cargol) who is discovered in the forest in 1798, running around naked, covered in dirt, fighting and biting and scratching like an animal when he's captured by some rural folk. The boy can't speak, has no understanding of language, and has apparently never experienced the socialization of being around other people. Totally isolated and wild, the boy, eventually dubbed Victor, is a case study for what humanity is like in a natural state, without the accoutrements of language and social behavior that society has created.

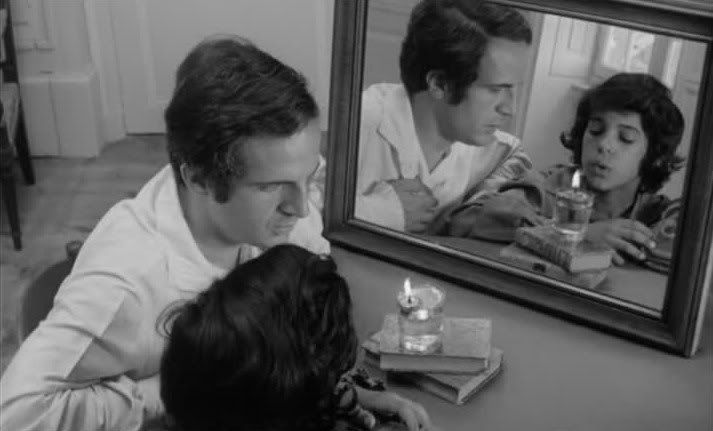

Dr. Jean Itard (Truffaut) hears of the boy and decides that he will take Victor into his own home, placing him in the care of his housekeeper Madame Guérin (Françoise Seigner) and trying to teach him language, trying to educate the boy and bring him into human society. It's another opportunity for Truffaut to study the rebellious spirit of a boy's resistance against societal rules: the film is dedicated to Truffaut's one-time child star Jean-Pierre Léaud, and one can easily see in Victor a trace of the same wild, anti-authoritarian qualities that Truffaut so admired in Léaud in The 400 Blows.

And yet The Wild Child possesses very little of those qualities. By this point, just over a decade after Truffaut's debut feature, the director who'd started out shooting rough and raw footage in the streets and decrying the "tradition of quality" cinema that had preceded the French New Wave, had himself been absorbed by that tradition, making films far more polished and conventional than one would have expected after his debut. In contrast to the unpredictable energy and enthusiasm of The 400 Blows, The Wild Child is somewhat dry and smooth, the sharp edges sanded away. Victor is a far wilder figure than Léaud's Antoine Doinel, but the film doesn't really do justice to his wildness, his unconventionality, his complete separation from human society. The result is a film of interesting ideas that's somewhat dull in its execution. Néstor Almendros' stark black-and-white cinematography is crisp and clear, but the film's more restrained tone clamps down on the poetic emotionalism of Truffaut's earlier portrait of uncouth childhood.

Most of the film is narrated by Truffaut's Dr. Itard, reading excerpts from his medical journals about the boy, which contributes to the clipped, clinical tone of this material. The film also moves at a very brisk pace, the long and arduous process of socializing this boy condensed to a highlight reel, complete with old-fashioned iris-in/iris-out effects to transition between scenes, a cutesy flourish that's completely at odds with the no-nonsense rapidity that otherwise characterizes the film. Truffaut makes the process of adapting this boy from a frenzied wild child into an at least superficially civilized kid seem like it happens quickly and incrementally, each new triumph of progress ticked off before moving on. Tellingly, he also cuts the story off before the sad conclusion of the real tale: in real life, Dr. Itard gave up on Victor soon after the events of this film are over, and Victor never progressed beyond the rudimentary fragments of language he's picked up by the end of the film. He spent the rest of his life in an institution, just as Itard's rival doctor had suggested at the beginning of this film. Truffaut elides any hint of this conclusion, choosing to end on a more ambiguous note, Victor having just returned from running away to resume his education with Itard. The ending hints that he could learn more, could actually become socialized and learn to speak, even if he still harbors a longing for the freedom he enjoyed in his former life.

That trace of melancholy about the loss of freedom is the film's strongest element, a cross-current to the unwarranted optimism implied by the ending. Cargol delivers a touching, raw performance, embodied entirely in his face, without recourse to any verbal expression other than a few grunts and a few hesitant words. He seems to long, viscerally and intensely, for the wilds of nature, and though he eventually accepts wearing clothes and eating with utensils and participating in Itard's language and alphabet games, he's still connected to nature. He'd rather stare out the window than watch his instructor. He'd rather run through the fields or stick his head out a carriage window like a dog in a car than play more of Itard's endless matching and memory games. One of the film's more provocative questions is the idea of whether the kid was actually better off not being discovered, if he was happier living wild and free without any attempt to fit in with a society that he'd never even known existed. It's at moments like this that Truffaut's poetic sensibility comes to the fore, in images of Victor running off through a large open field, escaping from the rules and restrictions of a world that he still doesn't fully understand, an image that strongly evokes the closing sequence of The 400 Blows, with Antoine Doinel escaping to the beach.

The Wild Child has periodic moments like this that reveal Truffaut's interest in this story and the ideas he wishes to explore through this wild boy's life. On the whole, however, it's a routine and undistinguished take on an inherently interesting subject, bolstered by its unique resonances with Truffaut's prior work. For a film that raises the question of whether its protagonist might have been better off living his life outside of society, it's a rather staid and conventional work that never truly does justice to the wildness at its core.

6 comments:

I have to disagree re "conventionality." This is one of Truffaut's best films, and highly self-critical one at that. Itard has his theories of human behavior and Victor is his guinea pig -- albeit treated with exquisite care and sympathy. Itard wants to prove that Victor "chooses" civilization over the wild. But as Truffaut shopws the boy ends up returning to Itard purely by chance.

The dedication to Leaud is interesting. Giving this youth, whose early childhood experiences reminded Truffaut of his own, a career was a great responsibility. Truffaut was well aware fo that. But as we know he could only take Leaud so far. The young actor truly blossomed under the direction og Godard (La Chinoise, Weekend, Le Gai Savoir) and above all Rivette (Out 1) It would certainly be unfair to hold Truffaut, or any of the others, responsible for Leaud's adult psychological degredation (I am of course referring to his attacking an elderyl neightbor with a hammer) He still works (eg. Le Havre) but looks quite alarming and far wilder than any "wild child" hosmentor/discoverer could ever have imagined.

How poignant to see Leaud now and then recall him doing the twist in 'La Chinoise'. Has it really been 45 years? 'Day for Night' was the last film of his I've seen --he sure was a diminutive beauty back then.

To me, Victer is like a housecat. We give him/her a comfy home, decent food, even our own food, give him space, toys and ityems to scratch his paws.

Yet all (s)he longs for is the freedom and excitement of the outdoors. Vivtor could be more like an animal of the wild than a human because he has no conception of death. At any rate, enough amateur philosophy.

That Truffaut chose to not tell the actual outcome of his story I find disturbing as it calls into question the honesty of the project.

Another excellent review. Congrats.

I like this Truffaut quite a bit. There is an obvious thematic similarity to Herzog's greatest masterpiece (THE MYSTERY OF KASPER HAUSER) and the story slowly becomes absorbing, aided by teh extraordinary turn from young Cargol, and some ravishing black-and-white cinematography by Nester Almendros. The film has a lot to say about childhood development, and there's that lovely 'learning how to speak' montage.

Great point about the strain of melancholy and as always a terrific review of a film I'll admit I like more. But fair enough points.

Hmm. I see what you're saying about how the film doesn't engage some important questions, particularly when considering that Itard later gave up on Victor, but I wouldn't go so far as to say that it's a dull film -- in fact, I'd argue it's one of Truffaut's most accessible works.

There are some Truffaut films I know I'm going to need to see again someday because I've forgotten a lot of what happened in them (Shoot the Piano Player, Day for Night), but with this one I actually appreciated that it was made conventionally; like 400 Blows, it's so focused on the people, the characters, etc., that it's damn-near impossible to forget. Some of those scenes, like Victor rebelliously biting Itard's hand, have really stayed with me.

Now, I submit I'm probably biased, in that the avante-garde films of the French New Wave don't do as much for me as the visceral ones, which may explain why I responded so strongly to this film even as a young high schooler. It may even explain why I prefer Truffaut to Godard, but again, it's that whole "visceral vs. cerebral, emotional vs. experimental" sort of thing.

Thanks for the comments, all. I figured I'd be in the minority on this one, as I have very mixed feelings on Truffaut in general - some of his films I like quite a lot, some do very little for me. This unfortunately falls into the latter category but you all make good arguments for its merits.

Sam brings up Werner Herzog's film on a very similar subject, and I prefer that one, which seems to have much more interesting stuff to say about humanity, wildness, and civilization.

And as Adam points out, I'm definitely more inclined towards the disparate directions taken by the other New Wave auteurs, rather than Truffaut's comparatively classical and commercial path. He made some excellent films in that classical mode (like Two English Girls, a film I love) but if I have to choose, give me Godard or Rivette or Rohmer or Chabrol any day.

Post a Comment