[This piece was previously posted as a guest review at Jeremy Richey's blog Fascination: The Jean Rollin Experience, one of the Internet's very best resources on Rollin.]

[This piece was previously posted as a guest review at Jeremy Richey's blog Fascination: The Jean Rollin Experience, one of the Internet's very best resources on Rollin.]Jean Rollin's best films use B-movie horror plots and low-budget production values as portholes into an eerie, unsettling dream world that ultimately has little to do with typical blood-and-gore horror movies. This is especially true of Lips of Blood, one of the director's finest works, and one of his most dreamlike and abstract. The film is a slow, sensuous study of the power of memory and the lure of childhood fantasies, a feverish dream of a film that chronicles a quest that's as much mental as physical.

Frederic (Jean-Loup Philippe) is at a party when he sees a photograph of a ruined castle that triggers a previously suppressed childhood memory or dream. He comes to believe that he's been to this castle as a boy, and that he's forgotten it for some reason; his childhood is a blur to him, and he's long felt disconnected from the stories that his mother (Natalie Perrey) has told him about his forgotten boyhood. The photograph instantly opens a path into his memories, stirring up images of a dreamlike night that he spent in the castle, watched over by a beautiful young girl (Annie Belle) dressed in white. He'd repressed the memories of the castle and the girl, but now that they've entered his mind again, he becomes obsessed, fixated on discovering the castle's whereabouts and trying to locate the girl.

Frederic is haunted by this dreamlike memory, and the film is all about the power that this fixation has over him. At the party at the beginning of the film, he compliments a girl on her perfume, prompting her to pointedly respond, "scents are like memories; the person evaporates but the memory remains." In Frederic's case, the memory too had evaporated for twenty years, but now it's wafted back up into his senses, and he begins seeing the mysterious girl from the castle everywhere. He goes to see a movie — the poster outside is for Rollin's The Nude Vampire, but the theater's actually showing The Shiver of the Vampires, suggesting how intimately connected all these gothic vampire fantasies are — and the girl appears in the theater, beckoning him to follow her. She leads him to a crypt, where Frederic unwittingly releases a quartet of creepy vampire girls (Catherine and Marie-Pierre Castel, Anita Berglund, and Hélène Maguin) who shadow him throughout the rest of the film, continually intervening to rescue him from the mysterious forces that seem intent on stopping him from locating the castle or the girl who dwelled within it.

The film moves at a typically lethargic, dreamlike pace, blending gothic horror imagery — bats and graveyards and vampire girls clad in gauzy robes — with a weird conspiracy thriller vibe. A photographer (Martine Grimaud) who tries to tell Frederic about the castle winds up dead, another woman poses, unconvincingly, as the girl from the castle, and a mysterious assassin tracks Frederic through the night, while the vampires stalk around the fringes of the plot, fading out of the shadows. Rollin's films have often been comparable to the surreal quest narratives of his contemporary Jacques Rivette, with worse acting and more nudity, and nowhere is that comparison more relevant than here. Rollin renders the city as a quiet, nearly unpopulated stage, pools of colored light highlighted in the darkness, shadows cast large and threatening on stone walls as Frederic wanders around the city, searching for answers and chasing phantoms through the streets.

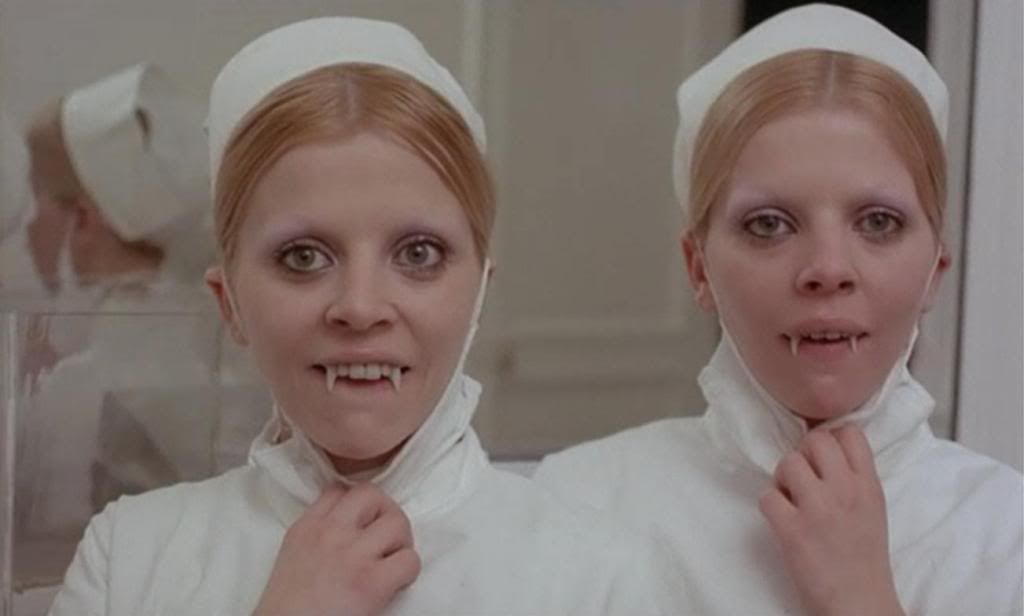

The film feels like a loosely connected series of set pieces, with Frederic's frazzled state of mind creating the sense of disorientation and confusion that dominates his increasingly desperate journey. He begins to doubt his own sanity: the girl from his memory, or his dream, pops into being and blinks out of existence just as suddenly, leading him through the night, eventually guiding him directly to the answer he seeks, the location of the castle from the photo. Meanwhile, the vampires attack and kill random people, baring their uncomfortable-looking fangs and bloodying their mouths on the necks of their victims. At one point, the Castel sisters disguise themselves as nurses in order to rescue Frederic from the mental hospital where he's been locked up by his mother, who seems to know something about all these secrets and mysteries.

Indeed, Frederic's mother provides the obligatory burst of exposition that suddenly explains the story towards the end of the film, setting up the fantastic final act in which Frederic confronts the true nature of his reawakened memories. He's found what he's been searching for, and in the final ten minutes of the film Rollin adopts a tone of lunatic celebration, reveling in the embrace of the supernatural and the bloody. The supernatural is rarely to be feared in Rollin's work. The supernatural is, instead, erotic, alluring, haunting, beautiful, a fixation for Rollin just as the castle becomes for Frederic. There is thus an air of real melancholy in the final act's confrontations between vampires and vampire hunters; Rollin's sympathies are obviously not with the men with their stakes, menacing these girls, but with the vampires themselves, so young and lovely and sensual, retreating in fear before the men. The vampires are the real victims, not to be feared or hated but desired, respected, adored, just as Frederic desires the girl from his memory, who is, of course, also a vampiress, using her power to lure him back to her, to get him to set her free.

Rollin makes the embrace of the supernatural a cause for celebration here, particularly in the ecstatic coda, in which the long-imprisoned vampire relishes her newfound freedom, taking pleasure in the sensuality of nature. Together, Frederic and his vampire love run along the striking, apocalyptic, by now very familiar beach that so often symbolizes the pathway between worlds in Rollin's work. It's here that Frederic embraces his fate and is reborn, and in the finale — at once gloriously silly and wonderfully romantic — the lovers sail off together in a coffin, heading off into a new undead existence together.

1 comment:

The film feels like a loosely connected series of set pieces, with Frederic's frazzled state of mind creating the sense of disorientation and confusion that dominates his increasingly desperate journey.

A stunning essay, just brilliant. I know Rollin divides the intelligentsia and the masses, but he's a visionary, a unique stylist unlike any other, (the cemetery scenes in this film are unforgettable) whose visuals are accompanied by a probing psychological slant. I've only seen three of his films, but this is one, and I applaud your fabulous appreciation.

Post a Comment