"You can learn a lot about a society by who it chooses to celebrate." So says former schoolteacher and current television interviewer Robin (Judy Davis) in Woody Allen's Celebrity, in one of those moments that Woody often inscribes in his films, where his authorial voice comes through loud and clear no matter which character the mouthpiece happens to be at any given moment. This line, coupled with the generic title, announces the film as Woody's commentary on the concept of celebrity rather than on any individual celebrities, and to that end he populates his film with a virtual cross-section of the kinds of people we, as a culture, tend to celebrate: movie stars, musicians, models, writers, New Yorker-style intellectual elites, athletes, TV newspeople, crime and accident victims, people suffering from rare illnesses, eccentric guests on Springeresque talk shows, even a famous priest who gets devout Catholics and nuns clustered around him like groupies at a rock concert. The point is obvious: there may be many types of celebrities, but the basic functioning of celebrity itself is the same, no matter the reason for the fame. The film teems with celebrities, though its two main protagonists exist on the boundaries of this world, continually rubbing up against the aura of celebrity in a series of encounters that reveal the parallel workings of the celebrity world and the "real" world. Woody's perspective is almost anthropological, as though he had discovered this strange new tribe of people and wanted to observe their odd mating rituals and inscrutable traditions. The camera, gliding with effortless ease under the guidance of Bergman cinematographer Sven Nykvist, gapes with equal wonder at the prodigious beauty of these people and the casual nastiness with which they treat one another. This satire of celebrity is, admittedly, not terribly original, but it is sharp, incisive, and has an acrid bite that makes it hit particularly hard. In some ways, Woody is taking aim at easy targets, but he knocks them over so forcefully, and with such brutal humor, that it's difficult to resist.

The film centers around the diverging paths of Robin and her ex-husband Lee (Kenneth Branagh) in the aftermath of their acrimonious divorce. By the end of the film, one of them will have been inducted into the annals of celebrity while the other continues to circle around the edges, always just outside the promised land. Throughout most of the film, though, Lee and Robin function as though the usual Woody Allen character had been split into two beings, each of whom ventures off on their own journey. And journey is an appropriate term, in the sense of a kind of epic quest; in many ways, Lee's episodic path through the film in particular is analogous to Dante's descent through the levels of Hell, exploring the many forms of sin and perdition among the celebrities he encounters in his job as a magazine reporter. The film opens with the letters "HEL," as in the Norse variation on the underworld, scrawled across the screen in skywriting, a message that's soon completed with one additional letter to read "HELP." Both words are equally appropriate for these characters, who are neurotic, self-conscious, insecure, and always trying to figure out how their life "should" be. In other words, they are very typical Woody Allen characters, but the fact that Woody is playing neither frees him up to explore some interesting variations on his usual persona.

For his part, Lee is the ugly and annoying aspect of Woody's neurotic charm. Branagh takes on Woody's signature stutter and the vacillation between insecurity and a preternatural confidence that allows him to walk up to the most beautiful woman in the room and come on to her. He has the ability, like Woody, to sell his charm, to make us believe that the pretty girls actually would go for this kind of goofy, sputtering fool, that in spite of or because of his insecurity these women really do see something in him. But whereas Woody's manner is always good for a laugh, Branagh makes this character frustrating in a way that Woody never does. He keeps pushing, keeps saying and doing exactly the wrong thing, stuttering his way into deeper and deeper trouble, until one wants to scream at the screen for him to cut it out. There's a sequence where Lee is trying to sell the volatile, self-centered actor Brandon Darrow (Leonardo DiCaprio) on his screenplay, and somehow gets roped into spending a wild night with the actor, shuttling between Atlantic City and New York and finally winding up in bed with the actor and two gorgeous girls. Throughout it all, Lee just cannot stop chattering, cannot keep his mouth shut about his screenplay for long enough to even notice, much less enjoy, what's going on around him. The scene ends with Lee, disinterested in sex, leaning over to ask Darrow, who's in the middle of passionately going at it with his girlfriend, what he thought of a scene in the screenplay.

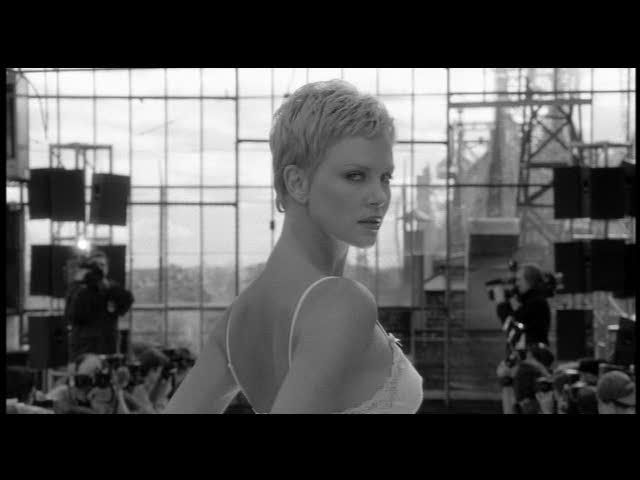

There are no words for this kind of exasperating character, and yet one quickly realizes that if Woody had played it, this scene would have been hilarious instead of pathetic and aggravating. Branagh takes the Woody persona to dark places, frequently going so far that it becomes hard to watch him. One quickly realizes that all those movies where we laughed at Woody's fumbling, nebbishy demeanor were actually about guys who, if we met them in real life, would turn out to be too much to take. Lee is, quite simply, an asshole, and Branagh does a great job of playing this dark mirror of the usual Woody character. Throughout the film, he goes through a succession of women — a "polymorphously perverse" supermodel (Charlize Theron), the stable, intelligent book editor Bonnie (Famke Janssen), the moody wannabe actress Nola (Winona Ryder) — and each time convinces them (and the audience), with absolute sincerity, that he is deeply in love with them. Each time, of course, it falls completely apart, sometimes through no fault of his own (the hilarious sequence with Theron, who is both stunning and a surprisingly good comic actress) and sometimes because he's just an utter jerk at heart.

Meanwhile, Judy Davis' Robin is the other half of the Woody persona, the earnest, yearning spirit in search of what she wants, even if she doesn't quite know what that is. Davis also has the Woody stutter, the neurotic tics that sometimes explode into full-blown public embarrassment, like when her internal monologue of rage against Lee suddenly erupts into out-loud screaming in the middle of a movie theater. Robin is, despite this outburst, the gentler side of Woody, and also the depressive side — where Lee lets his dissatisfaction out in the form of his passive-aggressive treatment of the women in his life, Robin simply sinks into sadness and self-pity. It's a no less ugly self-portrait for Woody, who by pouring himself into these two opposite halves seems to have exaggerated all the usual foibles of his screen personality. But Robin also represents an arc of self-improvement and success, even if it's the barbed success of celebrity. After the divorce from Lee, she meets the TV producer Tony (Joe Mantegna), who falls in love with her and convinces her to shed some of her inhibitions and come to work in television. As a result, Robin winds up pushing aside her ambivalent feelings about TV and celebrity, becoming a success and even seemingly finding happiness with her new career and new man.

In a sense, Robin's passage into celebrity is the American dream, a version of the familiar Hollywood narrative whereby the ordinary girl is made over, as if by magic, into a media princess of some kind. Woody skewers the myth subtly by having the princess in question essentially be himself in drag, but in many other ways Robin's story acts as a corrective to the film's overall thrust regarding the negativity of celebrity. Sometimes, Woody seems to be saying, too good to be true comes true anyway, and sometimes the rich and beautiful really are happy. In taking on these cultural stereotypes — DiCaprio as the drug-addled star trashing a hotel room, Melanie Griffith as a famous actress whose idea of marital fidelity is giving random strangers blowjobs but stopping short of "intercourse" — Woody is careful to include this glimpse of genuine happiness and connection. In some ways, he really does glamorize this celebrity lifestyle, idolizing it with the same outsider's awe that overcomes Lee whenever he's in the presence of these beautiful people. There's a reason that the film's black and white cinematography has such a gorgeous, metallic sheen, as though every image in the film was constantly being subjected to the glow of a thousand flashbulbs going off. The film simultaneously deconstructs and celebrates America's concept of celebrity. The film puts these people up on a pedestal and then asks, simply and often hilariously, "why?"

4 comments:

Brilliantly reviewed. And thanks for stopping by my blog!

It's just wonderful to read a review by someone who understands Allen.

This is the greatest write-up on "Celebrity" I've encountered, fabulously articulating every nuance that, for me, makes it such a rare, brilliant achievement and important work. Your insightful commentary articulates every defense I've been trying to personally summon up for "Celebrity" since I first saw it five years ago. It is, in my opinion, the greatest film of the nineties, and up there with the very, very greatest of Woody Allen's films.

Re-watching this has proven the film quite a bit better than I remembered. Still not one of my favorites, but still. You win, Ed. You win.

I'm glad you enjoyed it, Joshua. Woody's films do seem to improve over time, and revisiting some of the initially maligned ones can definitely be rewarding.

Post a Comment