Maurice Pialat's The Mouth Agape concerns itself with the body, with flesh and corporeality. It's a film about death and dying and illness, and also about sex, sensuality, pleasure, infidelity, love. Monique (Monique Mélinand) is dying, her body wasting away with cancer; she has only months left to live, and knows it. Her family gathers around her, tending to her and awaiting the inevitable. Her son Philippe (Philippe Léotard) is dutiful and loving, but he has his own life and his own problems, and in any event he can't bear to see his beloved mother suffering for very long. So he darts in and out, coming to see her often but seldom staying long. Her husband Roger (Hubert Deschamps) has had a long and stormy relationship with her, marked by serial infidelities and arguments and separations, and it seems that before her illness they hadn't actually seen very much of one another. But in his gruff, aloof way he cares for her now. Whenever he's not with her, he vocally wishes for it all to be over, saying he can't take it any more, and he retains his philandering ways right up until the end. He's an archetypal French dirty old man, using his clothing store as an excuse to get nubile young girls to strip down for him. His status as a lovable old man, affectionately called "the old goat" by the young girls, allows him to indulge his incorrigible nature, hitting on girls with blatant sexual come-ons that would get a younger man slapped. And he continues to visit his aged mistress (Jeanne Dulac), the woman who he had once wished to marry instead of Monique.

When he's with Monique, however, he is tender and caring, displaying a serene patience that his son utterly lacks. It is obvious that in his own inconstant way, he loves this woman, and is devastated by her departure — and perhaps by his own failures to be better to her when she was healthy. This is a film about the past as much as the present, and the dialogue allows the histories of these characters to unfold slowly, in short vignettes and stories that draw connections backwards from the present to old decisions and problems and mistakes. These people are all wounded and damaged in some way, they have come through strife to the places where they are today. They've hurt each other, too. Philippe, like his father, is congenitally unfaithful, seemingly unable to prevent himself from cheating on his wife Nathalie (Nathalie Baye). He seems to love her, to have real affection for her, and yet as soon as she's away from him he's picking up another woman, just because he can, one supposes.

In this film, death and sex are intimately woven together. Pialat alternates scenes in the hospital where Monique is wasting away — confrontations with mortality — with more sexual and sensual scenes. After visiting his mother in the hospital, Philippe returns home to find Nathalie in bed; he joins her and talks about his mother's illness and her impending death while his wife lies next to him, naked, not saying a word, sprawled out with the sheets draped casually across her breasts. She is quietly sensual and sexy, comfortable in her skin, and her presence is an unspoken counterpoint to Philippe's words. Later, a scene at the hospital cuts directly to Philippe passionately making out with a young woman named Corinne (Corinne Derel), stripping off her clothes to reveal an over-ripe body, fleshy and curvy, her buttocks distorted beneath his grasping hands, the imprints of her bra and panties still embedded in her skin. Her flesh, her body, the way her bra constrains and reshapes her proportions, recalls the opening scene in which Monique, stripped to her bra and a skirt, lies down for X-rays, the machine optically overlaying measurements and grid markings across her body. The decaying, dying body of Monique is continually contrasted against the young, supple flesh of the girls Philippe and Roger meet and seduce, and the continuity between these scenes emphasizes that both extremes are endpoints in a cycle, youth and beauty eventually aging into devastation and death.

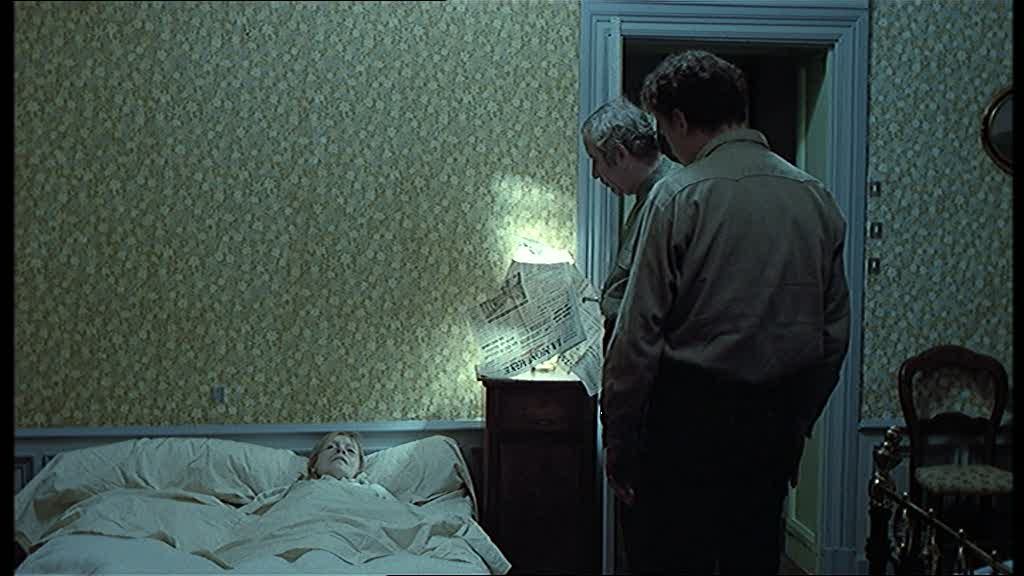

Mélinand gives an extraordinary and stripped-down performance here, speaking less and less as the film goes on, progressing toward a pale, zombified state, wrapped up in her sheets like a mummy, unable to move, her mouth convulsively opening and closing as the harsh gasp of her breath rattles and wheezes on the soundtrack. Pialat increasingly places her at the extreme lower boundaries of the frame, her prone form parallel to the frame and hovering just above its bottom edge, only her head visible above the sheets enfolding her, as though she were a drowning woman just barely managing to keep her head above the water.

The formal purity of Pialat's framings accentuates her increasing isolation, wrapped in a cocoon, her disembodied head gasping for air. A vast stretch of yellow patterned wallpaper fills up the majority of the frame above her. The camera often holds steady for long stretches of time, simply staring with discomfiting directness at the truths of mortality and disease. The camera occasionally quivers, subtly shifting and reframing — the hand of the cameraman weakening, his own human frailty and the limits of his body intruding into the picture — but it never looks away, never flinches from the realities of feeding, injections, the total failure of Monique's body.

This is a harrowing, deeply affecting film, with great patience for allowing the full complexity of these characters to reveal itself over time. Pialat understands that you can love someone, care for them, and still hurt them badly. He knows that the tenderness these characters show for each other in one scene is not necessarily inconsistent with the craven behavior they display in another. He also knows that these complexities, these complicated relationships and the characters' experience of sensuality, are ultimately trumped by the finality of death. In the film's last twenty minutes, the focus subtly shifts back towards Monique, the narrative paring away the various threads surrounding her until the camera is back to staring relentlessly at her wasted body as she gasps her last few breaths. Pialat does not look away, not from the prepping of her body after her death; not from the emotional catharsis of placing her in her coffin; not from the funeral itself, which he creeps up on from around a corner, his camera slowly arcing until the grieving family comes into view. The penultimate shot is a long view from the back of Philippe and Nathalie's car as they leave after the funeral, speeding away from death, even as the camera looks steadily backwards, like Orpheus leaving the underworld, unable to resist looking back on the scene of death once more.

4 comments:

thank you for an thought-provoking review. we're not familiar with this title, but after reading this synopsis we're intrigued.

next stop imdb: The Mouth Agape

thanks again,

..

.ero

Thanks, hope you enjoy it if you do see it. The Masters of Cinema label has just put out a fantastic new DVD in the UK, which also features a selection of Pialat's short films.

Thanks for the review Ed. Coincidentally I just saw this film at the Jeonju Film Festival in Korea, and really thought it was amazing. It was shown as part of a lecture by Adrian Martin, who provided some interesting details about how Pialat made the film. Originally, the film centered on the son and was over four hours long. Pialat kept working on the material in the editing room and eventually produced this 83 minute work with a completely different emphasis. This contradicts the whole idea of Pialat as a realist who just captures reality, but nevertheless what struck me about the film is its authenticity: the relationships, the settings, all had a feeling of being very lived in. My favorite scene is very early, an extreme long take of Phillipe and his mother in which the characters are so carefully and yet effortlessly established. I'm really looking forward to seeing more Pialat films. Hopefully you'll get a chance to review some more.

Marc, that *is* very interesting. I haven't delved into the extensive extra features on the MOC DVD yet, so I wasn't aware of the production facts. I get the impression that Pialat works very hard and intensively to create the *impression* of reality, rather than taking the cinema verité stance that if he just turns the camera on reality will somehow happen. His films definitely always feel real, often uncomfortably so, and I love the scene you mention, which suggests this long and rich history between mother and son.

I've seen a good sampling of Pialat and everything I see just makes me want to see even more. I'll be watching L'enfance nue and his Turkish shorts soon, and then I'll just have to wait anxiously for MOC to continue releasing his work. I'm so happy they're making a big chunk of his oeuvre available.

Post a Comment