Following up on my list celebrating

my film-viewing in 2010, here is my music list for the year. Unlike with the film list, I actually did listen to enough new music this year that I feel I can provide a list of my favorites from among the 2010 releases I heard. The list is ranked in rough order of preference, though the only placement I'm one hundred percent sure about is the #1 pick. These are my 27 favorite albums of 2010, a weird number I arrived at only because I couldn't stand to trim any of these fine works.

1. Michael Pisaro & Taku Sugimoto | 2 Seconds/B Minor/Wave (Erstwhile)

1. Michael Pisaro & Taku Sugimoto | 2 Seconds/B Minor/Wave (Erstwhile)I've heard a lot of great music this year, and a good portion of it has actually been from the lately very prolific composer Michael Pisaro, an exceptional artist with unique sensitivity and grace. (More on some of his other 2010 releases below.) But nothing else I've heard this year, or in several years in fact, quite matches this amazing album, a collaboration between Pisaro and the Japanese guitarist Taku Sugimoto, who quite independently of Pisaro has for some time now been exploring similar territory of restraint and space. Pisaro and Sugimoto, working separately within very vague guidelines about pitch and pulse, have crafted three pieces of sublime, shattering beauty. I find this album, frankly, overwhelming: it is so serenely poised, so evocative, simultaneously beautiful and unsettling, so coolly meditative and yet also deeply emotional in ways I find quite mysterious. It is difficult music to talk about, and trying to parse my feelings about these pieces has been a real challenge, but I will try anyway, because I believe this is a very important record and one that should be heard and discussed.

The first piece, "2 Seconds," is based around the idea of pulse, the exploration of slow, simple rhythms built from the clicking of woodblocks, the pinging of periodic electronic tones, and miscellaneous mechanical sounds. This steady pulse grounds the piece, as the musicians elaborate on this stable foundation in small ways, always returning to the simple, plodding rhythm at the core of the music. At times, the "beat" is provided by someone turning on a blender, or a wooden chair creaking beneath the musician, or a door slamming: the outside keeps creeping in, rubbing against the austerity and simplicity of the music. At one point, a watch beeps, blending in with Pisaro's pinging tones, a reminder of the centrality of time in this music, of time as the foundation of rhythm.

For "B Minor," the musicians agreed in advance on the key of the title and then devised complementary guitar pieces, with Sugimoto offering up lovely acoustic chords and Pisaro crafting a spacious quasi-melody out of high, clean electric guitar tones. This is simply gorgeous, some of Sugimoto's best guitar playing in years, recalling the delicate touch of his 1998 masterpiece

Opposite. The overlaid guitars, despite having been conceived separately, seem to communicate with one another in subtle ways, offering contrasting interpretations of the same minimal, minor-key melodicism. The final track, "Wave," incorporates processed field recordings of the sea and the wind alongside low, humming drones, all of it suggesting the hiss of the ocean, the slow pulsating of a wave, the mind-clearing drone of nature. This is music of great beauty and mystery, music as achingly lovely as it is challenging and strange.

[buy] 2. Swans | My Father Will Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky (Young God)

2. Swans | My Father Will Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky (Young God)This raging, roaring, overpowering album is the first studio recording in 14 years from this seminal post-punk outfit, who formed as grimy no-wave agitators in 1982 and broke up in 1997. Frontman Michael Gira has been far from inactive in the ensuing years, with solo albums, running his record label, and recording with the Angels of Light, but there's still something satisfying about this new reformation of his defining band. The album stomps and roars its way through this suite of dark, grand songs about the afterlife, spiritual yearning, and misanthropy, with Gira's deep — as in low, as in profound — voice issuing forth pronouncements as forcefully as the pulse of the music. Opener "No Words/No Thoughts" builds up a droning, surging sea of sound from repeated guitar patterns and chiming bells, while standout track "Jim" has touches of country twang winding around its slow, sinuous evocation of simmering rage. This is

heavy music, intense and raw, an album that makes it seem like Gira's Swans had never left, so seamlessly does it pick up the band's trajectory from hectoring 80s noise-punks to late 90s art-rockers.

[buy] 3. Terry Jennings/John Cage | Lost Daylight (Another Timbre)

3. Terry Jennings/John Cage | Lost Daylight (Another Timbre)This beguiling disc actually combines two very different works of modern composition. On the first five tracks of the CD, AMM pianist John Tilbury interprets five solo piano pieces by the little-known and seldom-recorded American composer Terry Jennings. These pieces are rich, beautiful melodic miniatures. Tilbury's delicate touch is familiar from his recordings of piano music by Morton Feldman and Cornelius Cardew, and he brings the same sensitivity, the same ineffably

right timing, to this music. Jennings' pieces have some relation to the lengthy, minimalist Feldman compositions for which Tilbury is best known as an interpreter, but without the pulsing repetition. These pieces are lovely and accessible, with a depth and emotional warmth that make returning to them again and again an absolute pleasure.

The other half of this disc is taken up by a very different type of music, a 40-minute interpretation of John Cage's "Music For Piano," with Tilbury on piano and Sebastian Lexer using electronics to manipulate and process the piano sounds. Tilbury and Lexer developed a very inventive interpretation of this piece, using chance procedures to determine various aspects of their playing, and then further shuffling things by editing and rearranging the piece through chance as well. The result is as far from the quiet grace and fluidity of the Jennings pieces as it is possible to get. The music is still very spacious, with lengthy silences and near-silences, but here broken up by nerve-jarring bursts of noise. Tilbury's delicate touch, so crucial to his piano interpretations, is felt only in isolated moments, a solitary note hovering in the midst of a buzzing electronic tone, or occasionally in a ringing cluster of notes. More often, the piano is felt in loud wooden bangs, the reverberation of the strings inside, and other incidental noises, as the electronics process Tilbury's playing into a humming, occasionally piercing stew of electronic tones. Taken together with Tilbury's Jennings interpretations, this piece offers up a response to the delicate, unaltered piano melodies of those shorter pieces. The disc as a whole offers up a dichotomy between the unhurried, straightforward playing of the Jennings pieces and the wildly deconstructive erasure of the traditional piano vocabulary on the Cage piece.

[buy] 4. Annette Krebs/Taku Unami | Motubachii (Erstwhile)

4. Annette Krebs/Taku Unami | Motubachii (Erstwhile)This is a remarkable duo meeting from two improvisers who are characterized by their unpredictability, their ability to challenge expectations and sidestep the usual conventions of improv language. This disc defies one to hear it as two people playing together in a room, even though that's apparently what it is — or rather, two people in multiple rooms. Krebs and Unami, mixing improvisations with recordings of various locations and sounds, have assembled a collage of sampled voices, field recordings, percussive crashes, bursts of electronic noise, shards of tape hiss and blurry rewinding, the occasional plucked guitar note, and so much more. The patchwork nature of the sounds used contributes to the sense of unpredictability, the impression that anything could happen. Voices whisper and chatter in different languages, loud crashes shatter the uneasy stillness, bits of guitar unexpectedly float up only to be drowned out by a reverberating bang, and a bassy drone briefly wells up and recedes. It's thoroughly original music, unlike anything else around.

[buy] 5. Michael Pisaro | Ricefall(2) (Gravity Wave)

5. Michael Pisaro | Ricefall(2) (Gravity Wave)Michael Pisaro's collaboration with Taku Sugimoto, discussed above, was one of the most stunning albums I've heard in a long time, but it didn't come entirely out of nowhere. Pisaro has been a remarkably consistent composer whose work — often dealing with field recordings, sound/silence, and sustained tones — has seldom been less than impressive. He's had a very strong year, too, with a flood of releases of almost uniformly exceptional quality. In addition to the Sugimoto collaboration, four other albums by Pisaro appear on this list, all but one of them recorded with percussionist Greg Stuart, a frequent and sensitive interpreter of Pisaro's complex scores.

Ricefall(2) is, as its title suggests, a score for rice falling on various surfaces, a simple concept turned into an occasion for a rigorous and sonically varied exploration of texture and density. The hour-long piece, performed by Stuart, consists of several distinct sections in which the rice is dropped onto various plastic and metal surfaces, producing cascades of pings and patters. The sound is engulfing and strangely beautiful, like a hail of metallic raindrops, all these harmonic overtones and little nuances of sound tucked away within the seemingly monolithic slabs of clattering, hissing noise. Listened to casually, the sound barely seems to be changing from one moment to the next, and yet within this dense drone is an inexhaustible level of detail and variety, constantly shifting and changing, revealing all the different subtle variations caused by the different interactions of the falling pellets as they collide with various solid surfaces.

[buy] 6. Pedestrian Deposit | East Fork/North Fork (Monorail Trespassing)

6. Pedestrian Deposit | East Fork/North Fork (Monorail Trespassing)I last heard Pedestrian Deposit on 2004's appropriately named

Volatile, an abrasive but carefully controlled noise assault. So I can't be sure if PD's Jon Borges has been slowly building towards the sound of

East Fork/North Fork over the course of the releases I haven't heard in the intervening years, or if this brooding, quietly affecting album is really as much of a hard left turn as it seems to me. Whatever the case, it's a remarkable recording. Borges — joined here by collaborator Shannon Kennedy — has retained the churning intensity of his noisier work, but here he's channeled and restrained the explosiveness. Textural crackling and rustling underpins surprisingly melodic plucked string tones, while a foreboding drone slowly burbles into life, and hints of bowed cello blend into the eerie atmospherics. It's haunting, even delicate music, equally gloomy and beautiful, sinister and sweet. The overall restraint makes the moments when Borges gets noisier even more effective, like the brief stretch of gravelly noise on "Strife/Meridian," a tense burst that's more an implosion than an explosion.

[buy] 7. Morton Feldman | Music for Piano and Strings Vol. 1 (Matchless)

7. Morton Feldman | Music for Piano and Strings Vol. 1 (Matchless)An amazing audio-only DVD that collects new performances, by pianist John Tilbury with the Smith Quartet, of two of composer Morton Feldman's lengthy works for piano and strings. Tilbury is inextricably associated with Feldman; his box set of the composer's solo piano pieces is absolutely indispensable. He brings the same patience and careful touch to this pair of slow, mournful hour-and-a-half-long pieces. On "For John Cage," Tilbury is joined by violinist Darragh Morgan for an exquisite and slowly evolving duet, the piano and scraping, droning violin working through repetitive figures with subtle variations that introduce a sense of tension to the work. The music is uniformly quiet and fragile, but with an unsettling variability in the rhythms that subverts the meditative aspects of the music. On "Piano and String Quartet," the fuller instrumentation lends a more varied palette to the hushed string harmonies, while the piano unfurls one chiming arpeggio after another, unhurried and separated by long moments of silence and stasis. The piece is even more spacious than "For John Cage," more airy and open, and equally affecting. The recordings on this set are crisp and dry, capturing the chilly tone of the strings and the rich resonances of the piano. Decay is crucial to Feldman, and Tilbury's piano tones often hover in the air, slowly fading into silence, being absorbed by the drone of the strings. These are bound to be definitive recordings of these essential pieces.

[buy] 8. Kevin Drumm | Necro Acoustic (Pica Disk)

8. Kevin Drumm | Necro Acoustic (Pica Disk)A new Kevin Drumm album is always a reason to celebrate. A new five-disc box set from the alternately reclusive and prolific noise guitarist is something else altogether. This impressive set collects new and archival recordings, reissues of tapes and LPs, and other odds and ends, but it's not at all a haphazard grab bag of second-tier tracks. Rather, it's a potent demonstration of just how intense and focused Drumm is, just how consistent his work has been even as he's varied his style tremendously. This set collects new and previously unreleased recordings (the sizzling

Lights Out and the disjunctive, jittery

No Edit), a reissue of a noisy double cassette from a few years back (

Malaise), a disc of archival recordings from all periods of his career (

Decrepit, which includes Drumm's material from his great split LP with 2673), and a full disc devoted to a longer version of the organ drone from 2000's

Comedy album. This wealth of material — much of which has more in common with Drumm's late 90s experimental guitar albums than the oppressive

Sheer Hellish Miasma or any of his recent ambient/drone work — provides a valuable look into Drumm's vaults. Not all of the material here is top-notch, but much of it is, revealing the astonishing fact that in many cases, the music he hasn't released over the years has been nearly as strong as what he has.

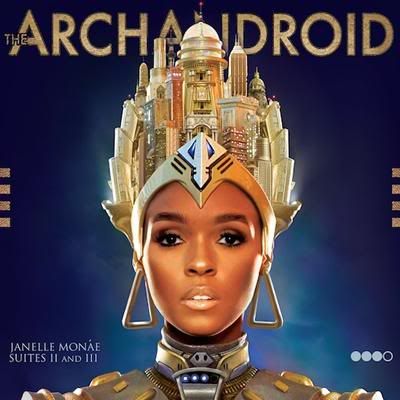

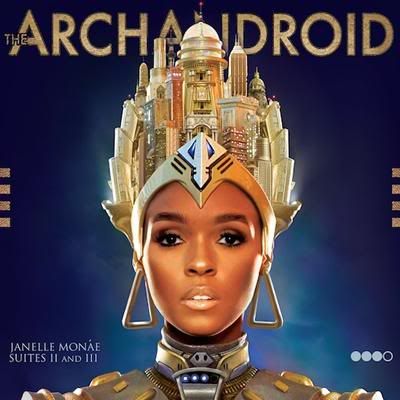

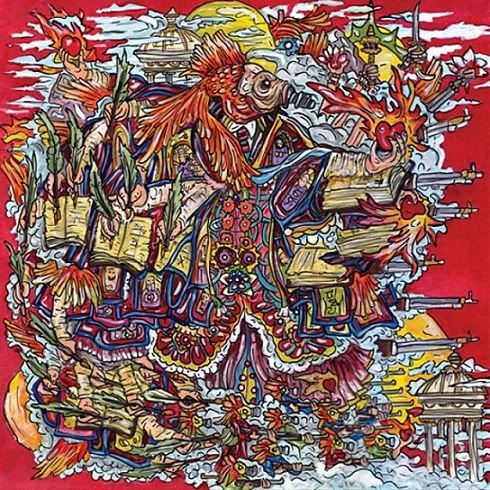

[buy] 9. Janelle Monáe | The Archandroid (Wondaland/Bad Boy)

9. Janelle Monáe | The Archandroid (Wondaland/Bad Boy)Janelle Monáe's debut album is a dizzying sci-fi epic, an overstuffed concept album on which Monáe demonstrates a restlessly creative, genre-hopping, fun and free-spirited sensibility.

The Archandroid encompasses soul, R&B, psych-rock, electro-funk, and hip-hop, but despite Monáe's lyrical references to schizophrenia and lunacy, the album itself never feels schizophrenic or disjointed. Monáe's expressive voice and eclectic, slightly goofy aesthetic tie everything together. The album is a delirious collage, perfectly balanced and varied enough that it never wears out its welcome. The overtures that introduce each of the album's two song suites recall Van Dyke Parks' orchestrations for the Beach Boys. On "Come Alive," Monáe appropriates the nervous bass pulse of the Violent Femmes for an edgy, anxious rocker. "Sir Greendown" and "Mushrooms & Roses" have a 60s psychedelic vibe, while the anthemic "Cold War" is propelled by a foundation of hard-driving drums. She's got genuine pop masterpieces in songs like "Faster" or the bouncy "Tightrope," which boasts a brisk, compact verse from OutKast's Big Boi. Whether Monáe is crooning on an R&B ballad, shouting and squealing like a rocker, or spitting out rapid-fire pseudo-raps, she's an engaging and powerful vocalist. She's also an utterly unique talent who's made one of the great pop/hip-hop/whatever albums of recent years.

[buy] 10. Graham Lambkin/Jason Lescalleet | Air Supply (Erstwhile)

10. Graham Lambkin/Jason Lescalleet | Air Supply (Erstwhile) It's interesting that all three of this year's great releases on the Erstwhile label (including the Pisaro/Sugimoto and Krebs/Unami discs mentioned above) have focused, in different ways, on assemblage and construction rather than straight improvisation — these three releases have augmented improvisation with compositional strategies, with editing and re-arrangement, with the injection of pre-recorded sounds. Lambkin and Lescalleet follow up on 2008's

The Breadwinner with the second part of a projected trilogy. It's typically mysterious music from this duo, who use field recordings and tape loops to craft unsettling aural landscapes. The album opens with "Because the Night" and "Layman's Lament," two tracks that juxtapose a textural drone with field recordings, layering sounds of wind and bird calls into the dense electronics. Then, on the suite of three shorter "temperature" tracks at the center of the album — "69°F," "68°F" and "67°F" — the duo explore rougher, more abrasive textures, occasionally exploiting the glitchy overload of sounds that seem to crackle and split apart as they increase in volume. The rough, harsh drones of these tracks are juxtaposed against various pebble-like rustling and clicking sounds, the sounds of the musicians preparing their tape recorders and machines, clicking computer mouses, bringing the studio into the music in the same way as they bring in the sounds of nature or the way that Lambkin's house seemed to provide the atmosphere to

The Breadwinner.

[buy] 11. Michael Pisaro | A Wave and Waves (Cathnor)

11. Michael Pisaro | A Wave and Waves (Cathnor)The title of

A Wave and Waves provides the breakdown of what its two thirty-five minutes pieces aim to accomplish: the first piece, "A World Is an Integer," is inspired by the sound of a single wave, while the second piece, "A Haven of Serenity and Unreachable," is inspired by the sound of multiple waves cresting and crashing in succession. Each piece is intricately scored for multiple overdubbed percussion events, and the resulting sound is tremendous: dense, detailed, incredibly deep. On the first track, the individual sounds — piano, various bowed or scraped percussion instruments, the clatter of pebbles, the crackle of leaves, etc. — build up into a massive drone that is both monolithic and infinitely detailed. Within the overall drone, there is a wealth of detail. It's a remarkable aural metaphor for the way in which a wave in the ocean can be both a totality and an accumulation of particles and parts. It is also a fascinating listen, as the sound is constantly shifting in small ways even while the overall sensation of a wave of sound washing over you is maintained. On the second piece, the sounds emerge from silence with the periodic regularity of waves crashing on a beach, reaching crescendos of rich, crackling sound that then fade back into the quiet. It's nearly as beautiful as "A World Is an Integer," and demonstrates how complex Pisaro's thoughts about nature are: he doesn't just simplistically attempt to recreate natural sounds but instead writes compositions where his ideas about the natural world are expressed, eloquently and evocatively, through the structure and feel of the pieces.

[buy] 12. Michael Pisaro | July Mountain (three versions) (Gravity Wave)July Mountain

12. Michael Pisaro | July Mountain (three versions) (Gravity Wave)July Mountain contains three different takes on a single piece, for field recordings and percussion. The first of these was originally available as a limited edition standalone release early in 2010, and it remains a gorgeous work, with the subtle percussion of Greg Stuart underlying and blending with the layered nature recordings of Pisaro. The remarkable thing about this piece is that the percussion track flows subtly and smoothly into the field recordings, so that it's continually unclear whether any given noise is a recording or a percussion part. In this way, the piece is dealing with fundamental questions about music and intentionality, about arranging sound versus playing it back as found. Is that rumbling the noise of a train going by or the sound of a bass drum? Are those chimes part of a percussion kit or are they hanging in someone's backyard, blowing in the wind? This expanded disc partially answers those questions on the two subsequent tracks, by including both Stuart's percussion part as an "instrumental" version without the field recordings, and a third version with different recordings. This demystifies (but can't ruin) the composition's blending of instrumental and found sounds, and reveals how inventively Stuart uses his drum kit to evoke natural sounds and maintain that ambiguity of sound sources. The original recording is still the most potent realization of the idea — and reason enough to consider this an essential disc — while the other two tracks seem like supplementary materials enriching and commenting upon the piece.

[buy] 13. Sun City Girls | Funeral Mariachi (Abduction)

13. Sun City Girls | Funeral Mariachi (Abduction)This is the final album from the long-running avant-rock outfit Sun City Girls, completed by brothers Richard and Alan Bishop following the death of drummer Charles Goucher. It is a perfect farewell to this endlessly inventive, unpredictable band, a surprisingly calm and focused effort that's a tribute to their musical influences and a return to the ethnic/garage/psych fusion of their 1990 masterpiece

Torch of the Mystics. The album is a loose homage to film composer Ennio Morricone, whose Western guitars and sweeping arrangements are married to the Girls' incorporation of faux-Arabic chants and psych rock feedback storms. The group offers up a faithful, mournful cover of Morricone's "Come Maddalena," but his spirit is arguably felt even more powerfully as the driving force, beneath wailing nonsense vocals, of "The Imam," which as its title suggests is Morricone by way of Abu Dhabi. The band also channels Syd Barrett's Pink Floyd, on "Holy Ground," a slow-burning rocker that sets the controls right for the heart of the sun.

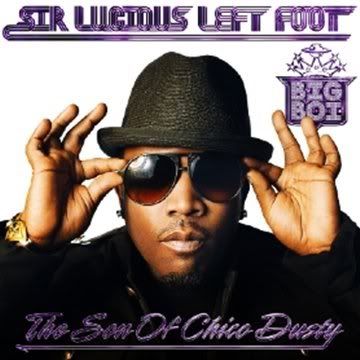

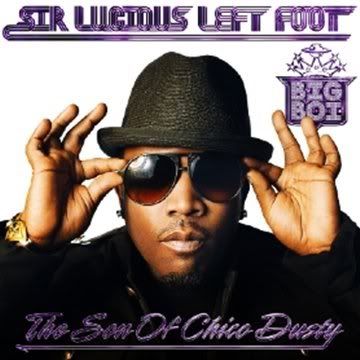

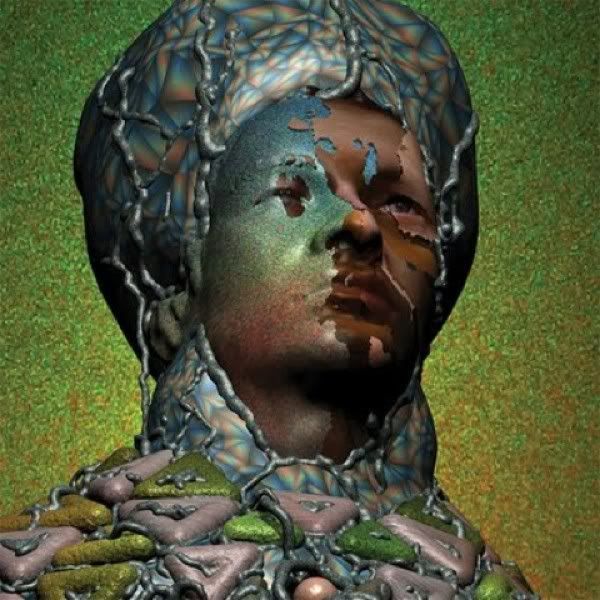

[buy] 14. Big Boi | Sir Lucious Left Foot... The Son of Chico Dusty (Purple Ribbon/Def Jam)

14. Big Boi | Sir Lucious Left Foot... The Son of Chico Dusty (Purple Ribbon/Def Jam)Remember when, back in 2003, Outkast's Big Boi and André 3000 released a double album of separate solo discs? Remember how everyone assumed that since André was the weird one that his disc would be the mind-blowing one? Remember how Big Boi's direct, sprawling, relentlessly fun

Speakerboxxx then proceeded to blow away André's more uneven funk pastiche

The Love Below? Now check out this new Big Boi solo disc, the first real new album to emerge from either Outkast MC since their 2006 soundtrack for

Idlewild.

Sir Lucious Left Foot is a near-perfect rap album, packed with soulful hooks and funky beats, overflowing with guest collaborators without ever sacrificing the coherent identity of the album as a whole. It's a whole album of highlights, more or less, from the raspy George Clinton guest spot on "Fo Yo Sorrows," to the moody crooning of "Hustle Blood," to the jittery energy of "Shine Blockas," to the fiery slow burn of "Tangerine," and so much more. It's all irresistibly fun and catchy, and Big Boi's verses are, as ever, marvels of creative phrasing.

[buy] 15. Michael Pisaro | Black, White, Red, Green, Blue (Voyelles) (Winds Measure)

15. Michael Pisaro | Black, White, Red, Green, Blue (Voyelles) (Winds Measure)Yet another Michael Pisaro release in a year where he's been responsible for much of the best music I've heard. This one is a two-hour cassette, featuring a piece for guitar played by Barry Chabala. The choice of doing a cassette release is an interesting one, and Pisaro clearly chose a composition that would work well in the medium, taking advantage of the tape hiss and low fidelity to augment the guitar. On the A-side, Chabala plays "Black, White, Red, Green, Blue," a piece divided into several sections, in which reverberating electric guitar tones cascade out of the silence, cresting and then fading back into the hiss of the tape. It's simple, repetitive music, but the warm, rounded beauty of the sounds, and the consideration of the tape's baseline hum as a counterbalancing element, makes this a very enjoyable recording. The B-side of the tape is even better, however. "Voyelles" is Pisaro's augmentation of Chabala's A-side guitar recording with additional layers of sine tones and recordings of various forms of tape hiss. Pisaro uses different tapes and different playback systems to get various colorations of low-level noise, which blend with the natural hiss of the tape itself and provide a kind of noise floor for Chabala's guitar. The combination of the guitar's rich tone with the sizzling electric noise of Pisaro's overdubs makes for a fascinating contrast, as well as a consideration of what constitutes silence, as here the pauses between Chabala's notes are mostly filled with buzzing, humming crackles and static. (Unfortunately this very rare release is out-of-print already, though I've heard that there are plans to reissue "Voyelles" as a CD.)

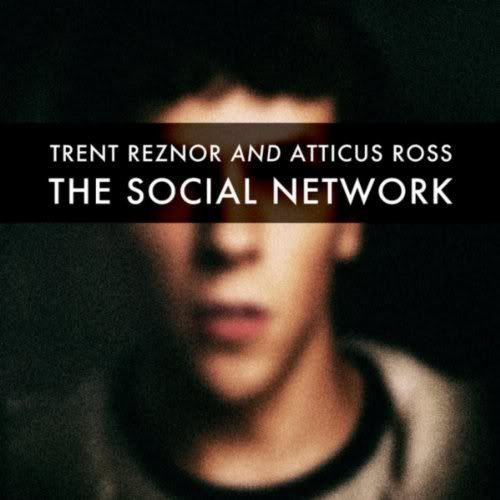

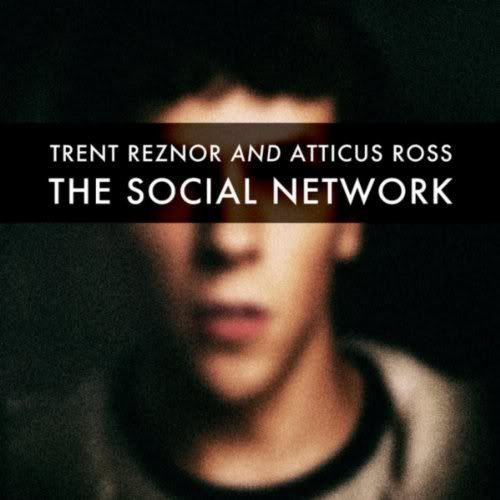

16. Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross | The Social Network (Null)

16. Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross | The Social Network (Null)This remarkably effective score for David Fincher's

The Social Network, by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, is a moody, darkly insinuating work that is especially well-suited to Fincher's chiaroscuro late-night shots of college campuses and his methodical examinations of computer programming and business deals. But even when divorced from the film it scores, this is a compelling album, some of the best music that Reznor has made, establishing a gloomy, low-key atmosphere that's seething with tension but rarely allows the violent undercurrents of the music an outlet. When it does, as on the chugging industrial grind of "A Familiar Taste" — the track that most directly recalls Reznor's Nine Inch Nails — the hard edge is sharpened by the drifting drones and suppressed menace that characterize the rest of the album.

[buy] 17. Joseph Hammer | I Love You, Please Love Me Too (Pan)

17. Joseph Hammer | I Love You, Please Love Me Too (Pan)This hallucinatory sound collage, released only on vinyl, utilizes looped, processed vocal fragments and shards of radio-ready pop music to create a dreamy, hazy, drifting piece of audio nostalgia. Far from indulging in the shallow appropriation of too many sample-crazed plunderphonics artists, Hammer digs deeply into a few evocative snatches of sound, drawing out the emotion in these snippets of song through hypnotic repetition. Hammer was once a member of the legendary sound art collective Los Angeles Free Music Society, as well as his avant/noise band Solid Eye, and this lineage shows in both the playfulness and the assured aesthetic he brings to this album. The individual sounds that Hammer is appropriating are unavoidably dated to various eras — notably the periodic bursts of poppy punk that are churned up towards the end of the LP's first side — but the overall effect is timeless, transcendent, and indelible.

[buy] 18. Kevin Parks/Joe Foster | Acts Have Consequences (self-released)

18. Kevin Parks/Joe Foster | Acts Have Consequences (self-released)This double disc set represents the finest work so far from these two American improvisers living in South Korea. The guitar/electronics duo makes music that is patient without being slow, spacious without edging into silence, carefully balanced between delicacy and abrasion. At times, Parks' guitar disappears into the electronic drones, blending in with the grinding machine sounds and hissing static. At other times, tonal clusters of guitar notes float up from the depths, surrounded with barbed bits of noise and static that make any melodicism seem fragile, unstable, liable to collapse at any moment. It's very tense, taut music, wonderfully restrained but with a great deal of emotional turmoil suggested in its rattling undercurrents and electric wire hum.

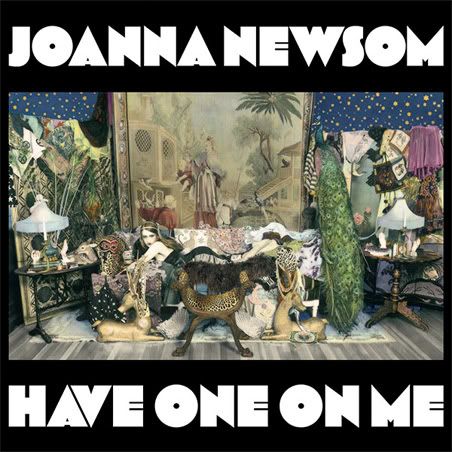

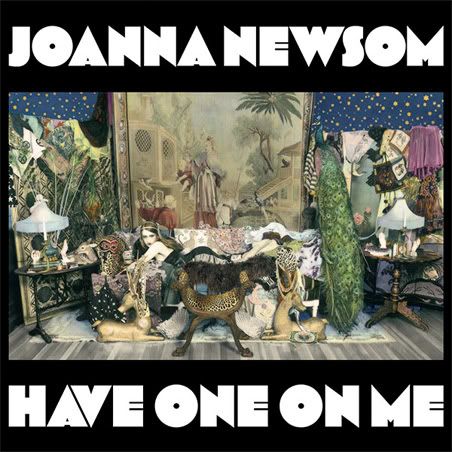

[buy] 19. Joanna Newsom | Have One On Me (Drag City)

19. Joanna Newsom | Have One On Me (Drag City)Joanna Newsom's second album,

Ys, was an exhilarating and fearlessly experimental work from an artist abruptly coming into her own, her wildly eccentric voice darting between the grandiose string arrangements of Van Dyke Parks with playful poetry. Her follow-up,

Have One On Me, is both more and less ambitious. It's a sprawling triple album that's stylistically varied and exhausting, perhaps even impossible, to listen to in one sitting. And yet it also represents Newsom stepping back, if only slightly, from the adventurous vocalizations and disconcerting arrangements of

Ys. Her voice has calmed down in the ensuing years; her squeals and squeaks and croaks, previously so integral to her persona, have been tamed by changes in her voice, and she comes across now as a much more approachable singer, like Joni Mitchell (an unavoidable reference here) with just a few touches of Björk. If

Ys was a bold, exciting statement of avant-garde songwriting,

Have One On Me is the work of a singer who's maturing and reaching back to her singer-songwriter roots without necessarily abandoning that experimentation or boldness.

Certainly, there's nothing staid about the lengthy title track's inventive structure, the way it slowly builds towards off-kilter but propulsive crescendos where her harp is augmented by whispery flute and galloping percussion. Newsom's sense of phrasing is as distinctive as ever, bouncing off the music rather than simply coasting along with it; she fits her voice into unexpected crannies in the music, singing against the rhythms, creating sublime tension between the music and her vocals. The album rewards such close, intimate listening, and demonstrates that even if Newsom doesn't always deliver precisely what one would want from her, she remains a fascinating, restless artist.

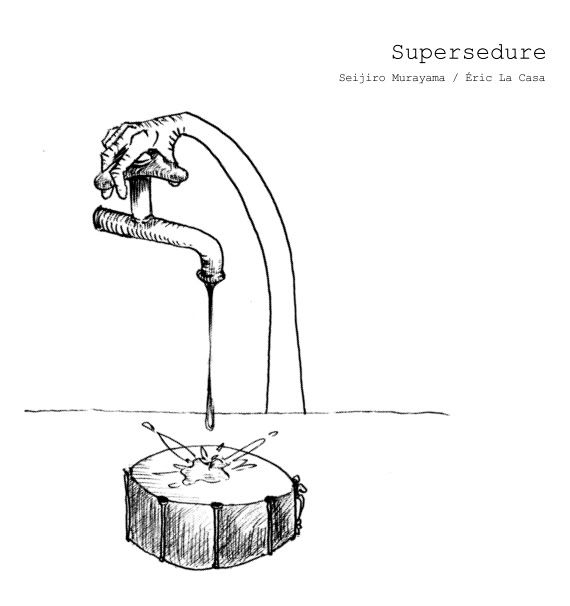

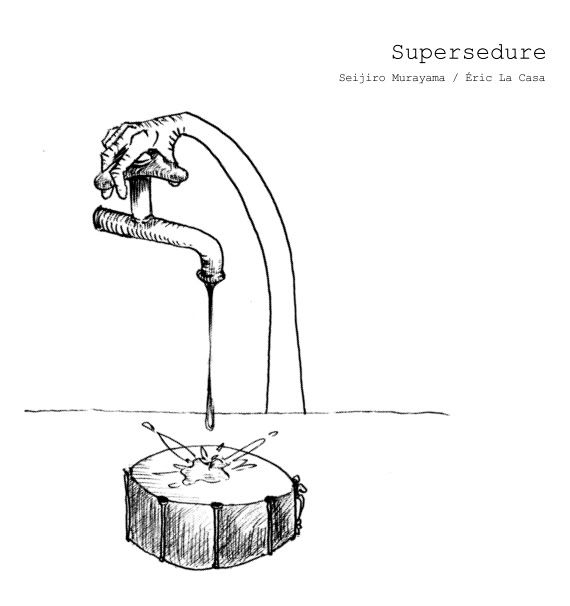

[buy] 20. Seijiro Murayama/Éric La Casa | Supersedure (Hibari)

20. Seijiro Murayama/Éric La Casa | Supersedure (Hibari)This is an odd one, part of the miniature trend for process-oriented sound art recordings that have been coming out of Japan in recent years. Murayama plays "snare drum and objects," while La Casa, a member of the French field recording/improv collective Afflux, is credited with "microphones and field recordings." This suggests that La Casa was responsible for recording Murayama, as well as layering in various field recordings that alternately blend with or offset the textures of the drum. The album is rough and disjunctive, contrasting sequences of hushed, low-volume textural improv against grinding, near-industrial sequences in which looped sirens or the chatter of a noisy street crash rudely against the drums. At one point, as Murayama builds a rattling, metallic cymbal drone, the hiss of steam and a background humming evokes a train station, so that the cymbal's reverberations become the sound of the train squeaking to a stop. These kinds of associations, suggestive but ephemeral, there and then gone again, keep burbling up through the music, as La Casa layers and processes multiple recordings of his collaborator or cuts in the sounds of vibrant urban life.

[buy] 21. M. Holterbach/Julia Eckhardt | Do-Undo (In G Maze) (Helen Scarsdale)

21. M. Holterbach/Julia Eckhardt | Do-Undo (In G Maze) (Helen Scarsdale)A lovely drone album on which Manu Holterbach uses the viola recordings of Julia Eckhardt as a foundation for explorations of texture and pitch. On the first of two long tracks, Eckhardt's droning, processed viola tones are gently nudged with little pinpricks of sound: rustling clicks and crackles, the hum of crickets, the gentle whirr of the wind. The viola remains at the center of the music, its resonances and textures creating the overall melodic drone of the music, while the other sounds nestle into its curves, darting about the edges of the drone. On the second track, Holterbach buttresses the viola with sympathetic drones sourced from various electrical equipment: hums, buzzes and sizzling tones that are tweaked and processed to blend in with Eckhardt's droning strings. The music often drifts at the edge of consciousness, hypnotically pulsing, only to surge back into wavering sheets of sound.

[buy] 22. Nachtmystium | Addicts: Black Meddle, part II (Century Media)

22. Nachtmystium | Addicts: Black Meddle, part II (Century Media)I loved Nachtmystium's last album,

Assassins, and this follow-up is more of the same while further emphasizing the surprising melodicism of this black metal band. Frontman Blake Judd has called parts of this album "black metal disco," and while in actuality the band's occasionally dancey beats and synthy melodies recall industrial metal more than

Saturday Night Fever, it's still a telling quote. Judd and his compatriots are consciously stretching beyond the narrow confines of black metal, even more than on

Assassins, fusing the darkness and roaring anger of black metal with bits and pieces of psych rock trippiness, pop-metal bombast, ambient drone, and whatever else they can think of. It's occasionally goofy and silly — that comes with the territory when it comes to black metal — but the band's unrestrained enthusiasm and energy goes a long way. This is a rousing, even fun record that, by combining black metal's urgency and extreme sound palette with an obvious desire to experiment and blend genres, comes up with something totally fresh and exciting.

[buy] 23. Of Montreal | False Priest (Polyvinyl)

23. Of Montreal | False Priest (Polyvinyl)Of Montreal have been on quite a roll in recent years. Starting with 2004's

Satanic Panic in the Attic, this band, which once fit so comfortably amidst the 60s-nostalgic psych-pop of the Elephant 6 collective, has been steadily transforming into a hydra-headed pop/funk/soul oddity. What makes this band of oddballs so thrilling in this current incarnation (which has so far spawned five albums of fractured pop lunacy in six years) is their unpredictability. Songs like this album's opener, "I Feel Ya Strutter," might lead with an uptempo trot as frontman Kevin Barnes waxes ecstatic about how lucky he is in love, but that doesn't preclude multiple sudden left turns as the song bounces and winds along, sometimes slowing down for tossed-off neo-soul diversions or 60s pop callbacks, sometimes offering up new melodies and new backdrops for each line of a verse.

And the follow-up song, "Our Riotous Defects," is if anything even loonier and loopier, incorporating white-boy raps on the hilarious speak-sing verses: "I did everything I could to make you happy/ I participated in all your protests/ supported your stupid little blog/ bought a Bo-Flex/ wore colored contacts to match your dresses/ everything your eye caught I bought/ and still we fought/ like Ike and Tina in reverse." Blending a disco pulse with orchestral pop flourishes and Barnes' characteristically off-kilter, high-pitched vocals, the song eventually coalesces into a dense melodic drone for the unexpectedly lush coda. It's these kinds of sudden shifts and serpentine structures that make this record, like all Of Montreal's recent work, such an utter joy.

[buy] 24. Taku Sugimoto | Musical Composition Series 1-2 (Kid Ailack)

24. Taku Sugimoto | Musical Composition Series 1-2 (Kid Ailack)Taku Sugimoto has for some time now been a fascinating figure in contemporary music, even as his music has often edged so far into minimalism that he risks seeming like he's stopped playing altogether. But his work has remained at least intriguing even in its extremes. This year he's released two new double-disc sets collecting music recorded over the past four years at the Tokyo concert series he runs, a total of four discs showcasing various aspects of Sugimoto's stripped-down aesthetics. It's a very self-conscious summation of where Sugimoto is at now, musically, and what ideas he's been exploring over the past few years. As usual, not everything hits home, but it's satisfying just to get such a comprehensive portrait of Sugimoto's compositions. The first volume is dominated by three lengthy and very minimal pieces composed for electronic sounds and household objects: extremely sparse, but "For Lightsabers," especially, with its carefully spaced bursts of sizzling noise, is a good example of Sugimoto's curiously affecting quietness. The second disc of this volume includes a pair of pieces that showcase Sugimoto's occasional collaborator Moe Kamura, whose whispery vocals add a very different element to Sugimoto's music. "Chair 2" is unsurprisingly spacious, interrupting the silence with bits of spoken word, solitary guitar plucks and brief, startling moments of melodic pop. The follow-up piece, "Modes of Thought," a highlight of these collections, follows through on that melancholy melodicism, as Kamura lows mournfully atop a tonal guitar accompaniment that is constantly threatening to melt into atonality.

The second of these double-disc sets continues the greater emphasis on guitar, and comparatively less emphasis on silence, that characterized that last piece on set 1. "Notes and Flageolets" is a gorgeous, chiming piece for five guitars, with passages of tonal guitar interspersed with the background hum of traffic noise. This is followed with a suite of 14 more guitar pieces with varying numbers of players, some pieces only a few seconds long, others lasting several minutes, some tonal and relatively active, others featuring just a few isolated notes amidst the silence. Like this project as a whole, it seems like a self-conscious summary of Sugimoto's approach to the guitar, working through the various moods and ideas he's explored with his primary instrument. The final disc is given over to two for-all-practical-purposes-identical 19-minute run-throughs of a piece with Sugimoto accompanied by a string quartet: droning and resonant, not bad but rather chilly and academic in comparison to the rest of the music on these sets. These four discs aren't the peak of Sugimoto's work — or even the peak of his more modest output in recent years — but they are yet another valuable addition to the ouevre of this confounding, maddening, thought-provoking, enthralling artist.

[buy] 25. Dirty Projectors & Björk | Mount Wittenberg Orca (self-released)

25. Dirty Projectors & Björk | Mount Wittenberg Orca (self-released)This isn't quite the delirious avant-pop concoction one imagines upon seeing that Icelandic songstress Björk has collaborated with the dazzlingly complex rockers in Dirty Projectors. Björk's contributions are spaced out across this mini-album enough so that, for much of its length, it sounds like a rather typical, if somewhat more low-key than usual, Dirty Projectors disc. That's not such a bad thing, either. These gentle songs are dominated by strumming acoustic guitars and elaborate vocal harmonies between head Dirty Projector Dave Longstreth and vocalists Amber Coffman and Angel Deradoorian. The tunes mostly feel like stripped-down versions of the band's 2009 masterpiece

Bitte Orca, although "stripped-down" is strictly relative here, and Longstreth's arrangements are as quirky as ever, as prone to detours and abrupt shifts in tone. When Björk does appear, her idiosyncratic voice is a perfect fit, cradled amidst the background harmonizing of Coffman and Deradoorian, who often provide a rhythmic component to augment the rarely used drums. In fact, Björk inhabits this sonic landscape so comfortably that one only wishes she showed up more often. As it is, it's a short and sweet little disc that leaves one wanting more. It's more of a tease than a fully developed statement, but what it has to offer is utterly charming.

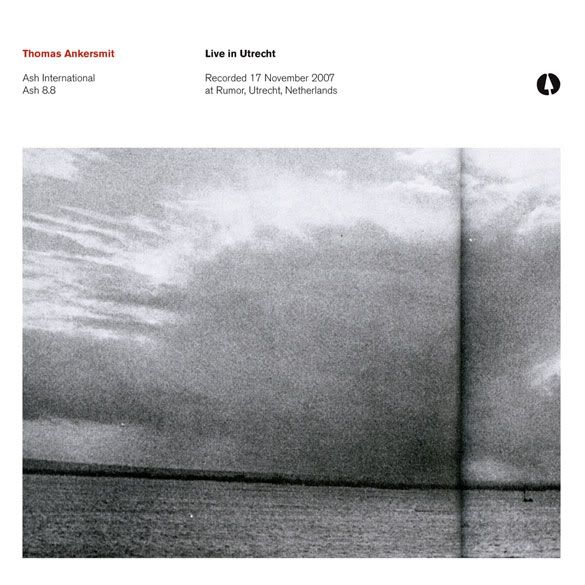

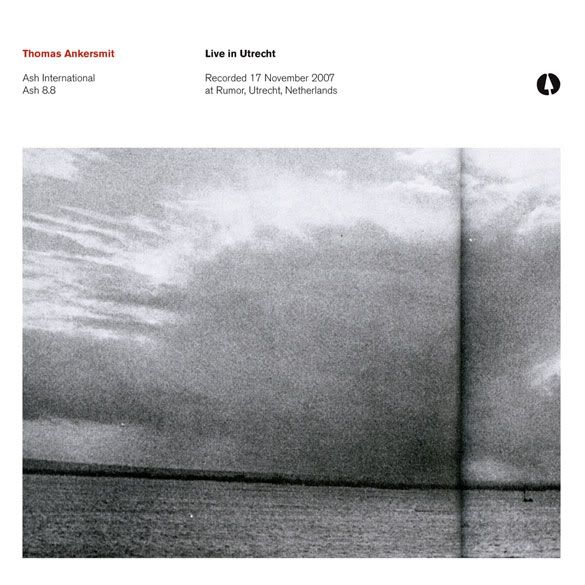

[buy] 26. Thomas Ankersmit | Live In Utrecht (Ash International)Live In Utrecht

26. Thomas Ankersmit | Live In Utrecht (Ash International)Live In Utrecht is the first widely available solo release from saxophonist Thomas Ankersmit, following a string of rare and obscure discs. This is an impressive proper debut from the young Dutch musician, who processes his saxophone into near-unrecognizability on this 40-minute live set. The piece opens with a buzzy drone that suggests the tonality of the saxophone without ever quite sounding like a sax. Occasional blurts and squeaks within the shifting layers of sound betray the instrumental origins of this music, but for the most part the sax is obscured within the glitchy, slowly mutating waves. After the introductory drone, Ankersmit ventures into even more abstract territory, exploring high, glistening tones broken up by various spikes or layered with shimmering, wavery sheets of sound. This is complex, intricate music, and it's hard to believe that Ankersmit realized this so well in a live setting.

[buy] 27. Yeasayer | Odd Blood (Secretly Canadian)

27. Yeasayer | Odd Blood (Secretly Canadian)When I wrote up my list of the

best music of the 2000s, I called Yeasayer's debut album

All Hour Cymbals "an eclectic, offbeat sound that goes down surprisingly easy," flirting with "abrasive electro-pop" and "summery harmonies" in roughly equal measures. Their second album might be described similarly, though it rearranges the elements of the band's sound, skewing more towards sizzling electro-pop and downplaying some of the world music appropriations and organic pop that characterized

All Hour Cymbals. This sophomore album is maybe not

quite as joyously great as the first one, but it's a worthy successor nonetheless, bursting with straightahead bouncy melodies and loopy electronic flourishes that make these poppy delicacies that much more delicious. The album boasts an especially strong first half, but really it's all enjoyable: it's a consistent, infectious album that puts a lot of more mainstream pop efforts to shame. "Ambling Alp" is a clear standout, a relentlessly positive gem that sells its upbeat optimism by sheer force of its sugary electro melody. "Madder Red" takes a more meditative tone, with plaintive chanting atop a synthesized ebb-and-flow. "I Remember" sets its bittersweet, nostalgic lyrics against the swirling arpeggios of the music, which aurally suggests murmuring surf to accompany the song's memories of "making love on the sand."

[buy]