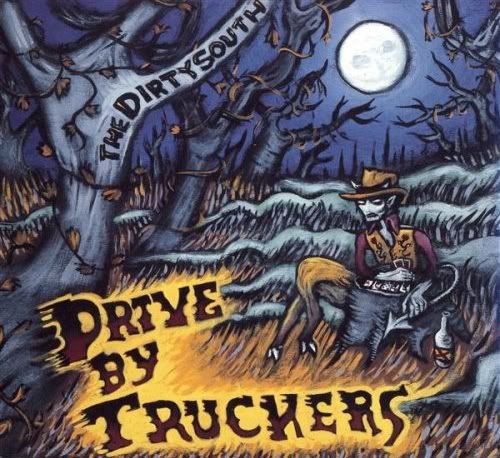

David Simon's

The Wire is quite possibly the most acclaimed and respected TV show of all time. After watching the first season in the condensed period of a week, I'm starting to understand why. The show's first season is a sweeping chronicle of a Baltimore police drug investigation that expands far beyond its original scope and begins digging into the corruption and evil at the deepest levels of city politics — and life itself. The show's genius is the way it starts with a very specific incident — drug dealer D'Angelo Barksdale (Lawrence Gilliard, Jr.) beats a murder charge and attracts the ire of crusading cop Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West), who more or less accidentally triggers an epic investigation into D'Angelo's uncle, the kingpin Avon Barksdale (Wood Harris) — and keeps spreading out from there. Tendrils eventually worm into the higher levels of the police department, into the political system, and especially into the communities where the drug dealers ply their trades.

This is a tight, complex show where plot threads slowly unfurl over time, reflecting the careful plotting of showrunner Simon, who co-wrote every episode (most with ex-cop Ed Burns, working from real events and real people) and planned out the season-long arc. This meticulous aesthetic pays off both in the big picture and in the details, as the season's overall story continually returns to the same themes and ideas. This is a story about endemic corruption that invades society at every level, and as a result there are no perfect characters here, only fluctuating levels of morality and ethics that sometimes prove to be only temporary. For instance, a judge kicks off the entire case by holding a stubborn moral high ground against a police department that's reluctant to go beyond basic duty in pursuing drug kingpins like Barksdale — but the judge's moral indignation more or less evaporates when the furor stirred up by the case threatens his judicial career in an upcoming election. Virtually all the charcters on the "good" side have similar limitations, whether it's the shady past of Lieutenant Cedric Daniels (Lance Reddick) or the casual graft of low-level officers like Herc (Domenick Lombardozzi) and Carver (Seth Gilliam), whose ironic arc involving missing drug money underscores how little it matters if you do good or bad, how right and wrong count less than if you get caught.

McNulty is arguably the moral center of this story and the one cop who consistently frames things in terms of right and wrong rather than thinking of policework, as his superiors do, in terms of statistics, where a closed case is a good one even if the real offender has escaped justice. The police department as envisioned here is a bureaucracy dedicated to getting good closed-case stats, and anything else — like McNulty's insistence on looking beyond the immediate case to deeply ingrained conspiracies and long-term investigations — is just a distraction. Still, McNulty is another compromised and flawed figure in a city that seems to be overflowing with them. Late in the season, he admits that what drove him into this investigation was not so much morality as his own pride, his desire to show off his own intellectual superiority in a culture where thinking outside the box is not exactly valued. Even more telling is the scene in which McNulty, without even hesitating, enlists his two young sons in a potentially tragic "game" of surveillance when by chance he spots Barksdale's right-hand man Stringer Bell (Idris Elba) at a grocery store. McNulty's a man obsessed, and though he's driven by basically good impulses — including a desire to do good at a deeper level than the usual shallow "case closed" police due diligence — he's not exempted from the series' depiction of a society in which doing good is, as often as not, punished rather than rewarded.

As if there was any doubt, Detective Lester Freamon (Clarke Peters) provides a perfect example of the future awaiting McNulty, a premonition of the end of the season. Freamon, though he's stuck shuffling papers in the property unit, is obviously an efficient and intelligent cop, and his back story parallels McNulty's: he pushed too hard on an investigation, disobeying orders from a superior, digging where he wasn't supposed to, and as a result he was sent to exactly the kind of boring, insubstantial assignment he didn't want, where he has languished ever since. The show is all about the consequences of pushing against boundaries like this: these characters are tightly constricted, locked into career arcs, unable to do anything to change things. There are rigid rules for what can be done and what can't be, to keep everything moving smoothly and the status quo firmly in place: the drug dealers deal, the cops hassle and arrest them but can never break up the business, and behind it all the politicians are deeply intwined with both sides of this drug war, with drug money flowing freely through the city into commerce and politics.

On the drug dealers' side, there are also those who seek to push against the status quo, to change things if possible, with equally disastrous though bloodier results. Throughout the season, D'Angelo struggles with his own burgeoning morality about the evils of his family business. As the season starts, D'Angelo's close brush with prison has caused him to be demoted from a higher level position that evidently kept him somewhat aloof from the worst of the street drug trade. Confronted with addicts and offhand violence day after day as he takes over a small operation in a project courtyard, he's increasingly conflicted about where his life has brought him. Not that he sees much choice; he was born into this, as the introduction of his scheming, tough-hearted mother late in the season makes clear, and he doesn't have a whole lot in the way of options. He wonders aloud why this business has to be so violent, why everyone around him seems so bloodthirsty when he just wants to be anywhere else. He tries to fit in only because he has to, telling a gory tale that later turns out to be the story of another man's cold-blooded murder.

Even more affecting is the arc of the young dealer Wallace (Michael B. Jordan), who works in D'Angelo's crew. Wallace is one of the most poignant characters over the course of the season, as set up in an intimate sequence where the kid, who seems to care for a tribe of even younger brothers and sisters in an abandoned apartment with stolen electricity, goes about his morning ritual of brushing his teeth and dispensing juice boxes to the other kids as they head off to school. He heads off to the courtyard, though, as the provider of the family, but he's too sensitive for the job. When his tip-off alerts Stringer Bell to the location of a rival, an associate of the colorful thug Omar (Michael Kenneth Williams), the criminal's bruised and burnt body (dumped in the projects to serve as a warning message) upsets Wallace so much that he withdraws into his room for weeks and turns to doing drugs instead of dealing them.

Wallace, even more than D'Angelo, is not cut out for this life. D'Angelo can adapt, dealing with the death and ugliness all around him, but Wallace shuts down when he encounters it close up. Of course, his decency and sensitivity — he's most at home, most natural and comfortable, when he's caring for and joking with the younger kids — are only weaknesses in this environment. He has no escape, no possibility of another life; he mentions going to school, but only once, as though he doesn't actually believe that's a real option for someone like him. His fate is inevitable but no less affecting; his final scene is the season's most jaw-dropping moment, made even more shattering by the realization that he was abandoned and forgotten by the cops who were eager to use him to build their case.

Wallace's death is a pivotal event because it begins the process of setting up the season's absolutely brilliant ending, which enforces the show's emphasis on stasis and entrenchment. The season ends the way it started, despite multiple shake-ups; there's a sense of circularity here, developing the idea that some things cannot be changed. The investigation which takes up the entire 13 episodes of this first season results in arrests and deaths, but the finale communicates the impression that nothing is really changing in any meaningful way, that there are simply new cogs taking the place of the old ones in a huge and powerful machine that is not going to stop running no matter what. D'Angelo's underlings take over for him in the courtyard without missing a beat, utilizing some of the street strategy that he introduced in the early episodes, but ignoring his sentimentality and self-doubt, which are simply dangerous traits in this "game." The images of the drug trade kicking back into motion after the close of the investigation have a mechanical precision that only reinforces that this is a perpetual motion machine: certain gestures and interactions are repeated over and over again, ritualized and carved in stone, unable to change in any real way.

The brilliance of

The Wire is the way that Simon, along with his co-writers and directors, inscribes these themes at every level of the story, in the littlest details and character arcs as well as at the macro level. So few characters here can really break out of the confines of their past, their upbringing, their situations to create a different life: drug addicts may kick the habit for days or weeks but are pushed back into it by circumstances and official indifference, dealers yearn for a less violent life but see no way to grab it, cops try to do good and wind up screwing up their own lives and accomplishing so little that their efforts seem to melt away as soon as they're done. There are hints of progression and change, notably in the characters of Freamon and Prez (Jim True-Frost), who get rare second chances that are all the more moving for how deeply

stuck everyone else seems. Change seems like an abstraction at times, as when Carver tells a drug dealer that he had once been a lower-class projects kid, too. If Carver is telling the truth, he represents someone who escaped a miserable and confining background to make something of himself, but the route from the projects to a detective's badge seems so abstract and remote that it might as well be a fantasy, for all the good it does most of the people living with this squalor and violence.

The enduring impression of this season is a portrait of a fucked-up world where it's all too easy for the bad to get traction and dig in its heels, and all too difficult for anything good to try to root it out. This is apparent in even the smallest details. The minimal budgets and filthy sub-basements of the Baltimore police are contrasted against the high-tech modernism of the FBI (who, post-9/11, only get interested in a crime if it can somehow be traced back to Bin Laden) when McNulty goes to visit an agent there, but the point is driven home again in a later scene when he meets the agent in a parking lot. The agent drives up in a shiny new car and automatically rolls down the windows, while McNulty has to lean over and laboriously crank his own window open. It's a subtle and subtly funny

mise en scène gag that reinforces just how limited the local institutions are in their ability to do anything large-scale and important.

That's an indication of just how rich this series is. Its thematic focus is very intense, and it's an almost unrelentingly grim depiction of societal malaise, but it still crackles with vitality, humor and intelligence that leaven what could otherwise have been an oppressive atmosphere. The show is consistently entertaining, with witty, slang-splattered dialogue and subtly grimy images of its sprawling urban warzone. Even the seemingly "small" characters who weave sporadically through the background crackle with life and wit — like a corpulent desk sergeant who can't seem to resist laughing with every line he says, no matter what he's talking about, but who shows some startling fortitude and intelligence when it comes to getting his hands dirty with policework. Simon's sprawling drug epic is equally brilliant whether one considers its big picture depiction of a society trapped in a self-renewing downward spiral, or its more intimate character stories.