Here is the second part of my annual cultural summary. On Monday, I posted about

the best films I saw in 2011 (though not the best films

released in 2011), and now here's a list of the best music of 2011. Unlike the film list, this one is limited to actual 2011 releases. Rankings are always subjective, and it just gets even more difficult and silly when the list in question combines various forms of avant-garde and electronic music with rock and rap and whatever else. So this is just a rough attempt at putting all this music I love in some kind of preferential order, even if that order would probably change if I posted the list tomorrow.

1. Taku Unami/Takahiro Kawaguchi | Teatro Assente (Erstwhile)

1. Taku Unami/Takahiro Kawaguchi | Teatro Assente (Erstwhile)

Taku Unami has for several years now been one of the most interesting and unique musicians in avant-garde music, a clever conceptualist who is seldom content to operate in any one mode for long, and who distances himself from so many other high-concept sound artists because his ideas almost always yield fascinating sonic results rather than being interesting only as theory. Takahiro Kawaguchi is one of several likeminded musicians in the modern Japanese electroacoustic scene, less prolific and less well-known than Unami but promising in his own right; his 2009 solo album

n, constructed entirely from ticking metronomes, is remarkable. Both artists have dabbled in the extreme minimalism of post-millennial Taku Sugimoto, and both artists have also expanded their palettes far beyond the self-imposed austerity of Sugimoto. Their first duo collaboration,

Teatro Assente, is anything but minimal, though it certainly suggests that the musicians are still intimately concerned with the relationships between sound and silence that have driven so much modern improvisation-based music, both in Japan and elsewhere.

Last year, my favorite album of the year was also an Erstwhile disc, a collaboration between Sugimoto and the composer Michael Pisaro, which pointed the way forward from a musical trajectory that had sometimes seemed destined to end in absolute, unyielding silence. Sugimoto and Pisaro maintained the austerity and serenity of their overlapping aesthetics while both looking back to the past (with a gorgeous harmonic guitar duo) and creating challenging, engrossing new syntheses of their sounds.

Teatro Assente represents another, very different, way forward, a refinement and expansion of the completely fresh sonic vocabulary of yet another great 2010 Erstwhile disc, Unami's collaboration with Annette Krebs. Like that album,

Teatro Assente challenges the listener to separate the two musicians' contributions, or even to think of it is as two musicians playing at all.

Rather, the album's distinctive array of clapping, clacking, rustling noises suggests an entirely aural narrative, an impression that the lengthy song titles — "She Walked Into a Room, and Found Her Absence." — do little to dispel. There's something very cinematic about this music, which was recorded in an old theater and sounds like it consists mostly of objects being moved around, sometimes violently, in space. In other words, its sounds are intimately linked with the circumstances of the recording process, even if it's difficult, if not impossible, to actually figure out the origins of these sounds when listening. Unami and Kawaguchi employ a large array of sounds: footsteps on wood floors, voices whispering like they're waiting for a show to start, sampled recordings, the ticking and clicking of tiny motorized gadgets, and various shuffling and banging noises from cardboard boxes and large objects being moved around. The music stimulates the imagination, encouraging the listener to invent narratives to accompany these puzzling sounds, or simply to imagine the musicians holed up in an old theater, spilling aluminum cans across the stage, spooling out rolls of tape to assemble Rube Goldberg sound-making contraptions, jamming on guitars, making their movements and their process of construction an inextricable part of the final product. This is fascinating, challenging music with a real sense of humor as well, as evidenced by whimsical gestures like titling one track "Knocking By Anybody of Nowhere (Dub Mix)" because there are lots of dubby echo explosions scattered amidst all the ticking metronomes and hissing noise. This is music bursting with surprises and mystery, a sonic film that's utterly immersive and unforgettable.

[buy]

2. Josh T. Pearson | Last of the Country Gentlemen (Mute)

2. Josh T. Pearson | Last of the Country Gentlemen (Mute)

In a way, I've been patiently waiting for this album ever since 2001, when Texas rock trio Lift To Experience released an epic, and epically weird, two-disc concept album about God, prophets, angels, the Lone Star State and the apocalypse.

The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads was and is a brilliant album, with Josh T. Pearson crooning and moaning hauntingly above alternately thundering and graceful rock n' roll testimonials. It was the kind of unforgettable, utterly unique musical statement that's hard to follow up, and the band never did; instead, they broke up, and Pearson all but disappeared except for a few low-key solo tours. Ten years later, he's back with a solo album that's every bit as epic and unforgettable as his old band's one and only album, but in an entirely different way. Gone are the jackhammering guitars and feedback and power trio intensity, replaced by stripped-down, spacious country motifs. For most of the album, Pearson's straining, soulful voice drifts like lonely tumbleweed through a desolate desert populated only by the sparse acoustic plucking of his guitar, with occasional strings winding through this emptiness like the sudden whine of a windstorm. It's a harrowing breakup and breakdown album, as infused with weird spirituality as

The Texas-Jerusalem Crossroads. It's confessional and despairing: Pearson pours out his soul in a series of lengthy, meandering pleas to God and/or lovers past and present. There's a deadpan, backwoods wit to song titles like "Honeymoon's Great: Wish You Were Her," but Pearson's voice transforms these wry puns into torturous expressions of guilt and grief. As that song winds through its 12 agonizing minutes, Pearson runs through an emotional gauntlet, wrestling with the conflicting feelings of passion and duty, and finally concluding that he's so weak that, ironically, he'll always desire whoever he isn't with.

[buy]

3. Clams Casino | Instrumentals (Type)

3. Clams Casino | Instrumentals (Type)

Hip-hop producer Clams Casino has recently risen to Internet prominence crafting tracks for rappers like Lil B and Soulja Boy, but this album of rap-less backing cuts suggests that his dense but ethereal music is perhaps best suited to stand on its own. These are instrumentals, but they're not entirely without voices, since vocal samples — wordless hums and trills or compulsively looped snippets of lyrics — play a big part in Clams Casino's sound. The music has an epic, soulful sound, stitching together lush, shoegazer melodies, caked in fuzz, with dreamy vocal samples and drums that seem to kick in slow motion. On "The World Needs Change," a pitched-down voice croons woozily through a hazy fog in which lullaby chimes are like sparkling stars showing through in a cloudy sky. On "Illest Alive," he samples Björk's "Bachelorette" and chops it up until the Icelandic singer's distinctive voice is stretched out into an eerie drone, with only occasional snippets of coherence. Towards the end of the album, the producer drops a few stripped down, minimal tracks that seem to demand a rapper's presence to weave around the beats, but for the most part

Instrumentals feels like anything but a collection of backing tracks waiting for an MC.

[buy]

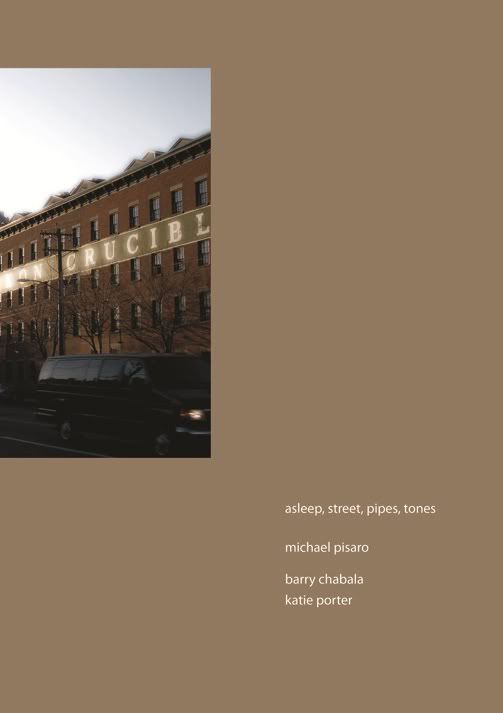

4. Michael Pisaro | Asleep, Street, Pipes, Tones (Gravity Wave)

4. Michael Pisaro | Asleep, Street, Pipes, Tones (Gravity Wave)

This is yet another in a long string of fascinating, highly original compositions by Michael Pisaro. On this piece, Pisaro alternates in three-minute segments between two types of material: a duet between Barry Chabala (guitar) and Katie Porter (bass clarinet); and an electronic studio assemblage of field recordings, organ samples and other processed bits and pieces. The two groups of material alternate throughout the piece, but the whole never feels disjointed. Instead, Pisaro seems to be exploring, through two very different approaches, a unified territory of tranquil held tones and meditative late-night quietude. The instrumental sections focus on sustained tones from the bass clarinet and answering guitar pings, creating an aural atmosphere not all that different from the stretched, droning organ notes of the electronic sections, so that the various sources, acoustic and electronic, "live" or post-processed, begin to bleed into one another. There's also a lot of variety in the textures and sounds that Pisaro builds from these disparate sources, with the organs sometimes ringing out in rich, bell-like resonances and other times sending out bassy reverberations. The instrumental sections, meanwhile, gradually grow more complex and intricate, progressing from the stasis and simplicity of the earliest segments to the spacious melodicism of the final instrumental stanzas.

[buy]

5. Eleanor Friedberger | Last Summer (Merge)

5. Eleanor Friedberger | Last Summer (Merge)

The first solo album from the Fiery Furnaces' lead singer proves that Eleanor's brother Matt is not the sole visionary behind that band's aesthetic.

Last Summer is recognizably the work of one half of Fiery Furnaces, full of catchy melodies and elegantly phrased lyrics, but the song structures here are more direct, less twisty and schizophrenic. Opener "My Mistakes" leaps immediately into a chugging, muted rhythm with Eleanor intoning, "you know I do my best thinking when I'm flying down the bridge," as though she's already in the middle of a conversation, before squeaking, squelching synth melodies fill out the background behind her. These songs don't have the modular structures so favored by brother Matt for the siblings' main band, but they're hardly simple songs. In fact, they're densely packed with aural detailing, layers of piano, handclaps, guitars and synths that back up Eleanor's distinctive voice. There's quite a lot of variety here, too, ranging from the lilting, mantra-like "Inn of the Seventh Ray" to the faux-funk pulsations of "Roosevelt Island" to the hushed, confessional "One Month Marathon" to the anthemic rocker "I Won't Fall Apart On You Tonight" to the gorgeous hymn of the closer, "Early Earthquake." This is just a fabulous pop album where every song is a winner; there's not a single wasted minute here.

[buy]

6. Greg Kelley/Olivia Block | Resolution (Erstwhile)

6. Greg Kelley/Olivia Block | Resolution (Erstwhile)

This first duo meeting between electronic composer Olivia Block and trumpeter Greg Kelley is a bold, noisy affair. After the slowly building, churning drone of the long opening track, one might be prepared for an album of more of the same, but on the rest of the disc, Block and Kelley mostly avoid such comforting drones for noisy bursts of clattering percussive sounds, rumbling bass, and spiky

musique concrète-like electronic fields. Kelley sends whistling, humming breaths of air through his trumpet, often placing metal plates against the bell to add a distinctive vibrating, resonating metallic quality to his sound, and Block responds with a varied palette of electronic tones, piano, and all sorts of unidentifiable industrial clamor. There are also moments of beauty scattered throughout the album, as on the guttural hum of the closing track or the aptly titled "How Much Radiance Can You Stand?", on which Block's clean, spacious piano playing recalls the work of AMM's John Tilbury. The two musicians seem utterly in sync — at one point, Kelley weaves whistling, almost-sounded horn lines around Block's high-register sine waves, nearly matching her sounds — and the resulting music is visceral and intense. It might almost even register as aggressive if there weren't also such a sense of playfulness to it, particularly on the whimsically titled "Some Old Slapstick Routine," on which the musicians unleash a veritable barrage of percussive noise.

[buy]

7. Tom Waits | Bad As Me (Anti-)

7. Tom Waits | Bad As Me (Anti-)

From the opening seconds of album opener "Chicago," with its frantic chase sequence staccato stuttering of horns, it's already apparent that Tom Waits' latest album is going to be great. And indeed it is. Instead of offering up another drastic stylistic shift in a career that's already seen a few, Waits is tying everything together, offering up a career summary that caps off a few decades of consistently remarkable work.

Bad As Me encapsulates Waits the genre-blending New Orleans jazz avant-gardist familiar from albums like

Rain Dogs ("Chicago," "Talking At the Same Time"), Waits the heart-on-his-sleeve balladeer ("Kiss Me," "Face To the Highway"), Waits the junkyard industrial growler (the title track and the martial "Hell Broke Luce"), Waits the bluesy rocker ("Satisfied," which sounds like a defiant response to the old Rolling Stones classic, made relevant by the presence of guest guitarist Keith Richards). Waits' distinctive whiskey rasp is in fine form here, and the album's diversity extends to the multiple personae and attitudes he channels through his ragged but versatile pipes. He shifts seamlessly from an eerie high-pitched whine to a wounded bar singer croon to a mouth-full-of-granite Cookie Monster growl. There's even the surprising highlight of "Get Lost," on which Waits affects an Elvis-like drawl for a swinging, rocking old-school stomp, an infectious plea to let loose and party. Waits has rarely misstepped, and for an artist of his daring and longevity, there are a surprisingly small number of duds in his career.

Bad As Me is a worthy addition to that impressive history.

[buy]

8. The Magic I.D. | I'm So Awake/Sleepless I Feel (Staubgold)

8. The Magic I.D. | I'm So Awake/Sleepless I Feel (Staubgold)

In recent years, several musicians from the Berlin and Vienna electroacoustic improvisation communities have begun experimenting with pop and song forms, creating fusions of abstraction and song. One of the most compelling results of this experimentation has been the work of quartet The Magic I.D., who debuted in 2008 with

Till My Breath Gives Out. Their second album is arguably even better, with lilting, sweet tunes arising organically from the relaxed, low-key textural backdrops that the band weaves together. Computer musician Christof Kurzmann and guitarist Margareth Kammerer take turns on vocals, sometimes singing in gentle counterpoint, sometimes trading verses or songs. Where Kurzmann's voice is a dry, sing-speak mannered drone, Kammerer has a deadpan cabaret theatricality that contrasts nicely against the general restraint of the music. These voices drift through near-abstract backgrounds of gently strummed guitars and buzzing, humming electronics, but the most powerful musical presence here is provided by the dual clarinets of Michael Thieke and and Kai Fagaschinski, one panned hard right and one hard left. Their reed playing is sometimes rich and melodic, while at other times they provide droning sustained tones that blend well into Kurzmann's electronic soundscapes. This band's integration of song form with electroacoustic sound is counterintuitive but perfectly realized, and they're exploring territory that's virtually unique to them and a small cluster of related groups.

I'm So Awake/Sleepless I Feel is the best statement to emerge from this scene yet, a daring and charming album that suggests just how fertile this territory is.

[buy]

9. Thomas Ankersmit/Valerio Tricoli | Forma II (Pan)

9. Thomas Ankersmit/Valerio Tricoli | Forma II (Pan)

This collaboration between saxophonist Thomas Ankersmit and electronics manipulator Valerio Tricoli follows up on the former's excellent live disc from last year, representing a long-awaited burst of activity for the young and formerly anything-but-prolific musician. On last year's

Live In Utrecht, Ankersmit mixed tapes provided by Tricoli into his live, improvised saxophone/electronic manipulations, and the results were stunning. Here, Tricoli joins Ankersmit as a full collaborator, and if anything it's even better. The presence of Tricoli as an active participant deepens and thickens Ankersmit's looping and processing of his sax playing; the droning, complex electronic stew assembled here (mostly in post-production rather than live) seems even deeper and darker than that heard on

Live In Utrecht. Sometimes, the duo simply build a rich but static multilayered drone, as on the overwhelming "Takht-e Tâvus," which feels like staring into the sun. More often, these pieces fizz and crackle with tension and activity, as the two players react to one another's minute shifts in the overall high-frequency broth. Ankersmit rarely betrays hints of his saxophone in a blurt or squeak of recognizable playing, and even these momentary signifiers of acoustic instrumentation are quickly looped and processed, swallowed up by a sea of sizzling electronics and static noise.

[buy]

10. Lil B | Im Gay (Im Happy) (Basedworld)

10. Lil B | Im Gay (Im Happy) (Basedworld)

To say that Lil B is prolific is to severely understate the sheer quantity of material pouring forth from the young rapper, an Internet phenomenon who makes so much music that even a 600-song compilation of his work wasn't exhaustive. He's made more music in 2011 than most artists make in their entire careers, and that's true even if you just count his "official" mixtapes. He's also a rapper who loves provocation, as evidenced by the title of this particular mixtape — he's not, in fact, gay — and the parenthetical that seems like both a reflexive defensive maneuver and a way of underlining the ha-ha-only-kidding nature of the title. And then, the actual music is something else altogether, finding Lil B (a rapper of many styles and preoccupations) in his diaristic introspection mode, delivering naïve ruminations over soulful, low-key beats. With his patient, halting, occasionally off-kilter delivery, Lil B raps about race, self-image, religion, and mortality, his relaxed vocal style giving the impression that he's forming his thoughts in real time. It's an optimistic album, but not without a sense of darkness: he mentions suicide, slavery, racial profiling, and other societal evils, only to emphasize that personal struggle and positivity can help individuals get past these obstacles. That thematic focus is most apparent on album highlight "I Hate Myself," which lays its emotional stakes bare by underpinning Lil B's raps with a swooning Goo Goo Dolls sample. The lyrics on this track have a clever structure, enumerating all the ways in which society teaches black people to hate themselves, before flipping the song's meaning around with a coda in which Lil B declares, "everything that I've seen was a lie/ I'm not ready to die/ I love myself."

[buy]

11. Ellen Fullman | Through Glass Panes (Important)

11. Ellen Fullman | Through Glass Panes (Important)

Ellen Fullman is a highly original composer/performer who plays on an instrument of her own invention, the descriptively named long-stringed instrument, which consists of a set of fifty-foot-long wires that she bows and vibrates with her fingers. The instrument produces unique, droning layers of resonances, rich and full and subtle. On the four pieces that make up

Through Glass Panes, Fullman explores the contours of her instrument (which she has been playing since 1981) in several different settings and with different combinations of collaborating musicians. "Never Gets Out of Me" juxtaposes the deep resonances of the long-stringed instrument with the comparatively traditional mournful cello tones of Theresa Wong, and the effect is striking and melancholy: Wong's gorgeous minor-key melodies seem like condensed versions of the stretched-out tones that Fullman pulls from her instrument, as though the two musicians are exploring the same idea on entirely separate time scales. On "Flowers," Fullman is joined by cellist Henna Chou and violinist Travis Weller, and together the three musicians craft a much fuller and richer sound, with crystalline structures assembled from their unison string tones. This piece was recorded in an abandoned power plant, and the recording emphasizes the hollow spaciousness of the surroundings, as well as setting off the string drones from the delicate birdsong heard in the background. The title track is composed for two performers with box bows — hollow, curved wooden blocks — which create syncopated percussive patterns on the elongated strings of Fullman's instrument. The effect is almost folksy and guitar-like, recalling Henry Flynt's front-porch minimalism, with the rhythmic beats of the box bows contrasting against the underlying droney harmonics. Only on the final track, "Event Locations No. 2," does Fullman's instrument stand alone for a solo piece, with the droning strings creating layers upon layers of beautiful, emotionally charged overtones.

[buy]

12. G-Side | The One... Cohesive (Slow Motion Soundz)

12. G-Side | The One... Cohesive (Slow Motion Soundz)

This Alabama hip-hop duo has had a prolific few years, and they bookended 2011 with this back-to-front masterpiece in January and the more uneven, but still impressive,

iSLAND, which came out towards the end of the year.

The One... Cohesive lives up to its title by being a totally consistent and cohesive rap album, unified by the production of the Block Beattaz, whose blend of rave-glow electronics, strings and piano, and skittery, complex beats provides the perfect backdrop for rappers ST 2 Lettaz and Yung Clova. At one point, they lament that critics simplistically compare them to Outcast, and indeed the comparison mainly makes sense in terms of the broad family resemblance of Southern rap; there's no question that they have their own style. The album's packed with guest rappers and singers — every track has at least one guest — but these contributions are smoothly integrated into the duo's sound. Indeed, such collaboration seems to be a big part of their ethos: the album is a celebration of forming a de facto family from musical collaborators and friends, and they tout the virtue of remaining loyal to their "inner circle." Coupled with the epic grandeur of the music, the lyrics are often stirring and emotionally complex, expressing positivity about the future and awareness of the poverty and troubles of the past. That is, when they're not taking a break to deliver a club banger oozing with hometown machismo, or a celebration of girls taking naked cell phone pictures. That's kind of key to the album's appeal, actually: despite all the introspection in many of the lyrics, G-Side never take themselves so seriously that the music stops being fun.

[buy]

13. Destroyer | Kaputt (Merge)

Kaputt

13. Destroyer | Kaputt (Merge)

Kaputt is a total curveball from an artist who had previously been in danger of settling too comfortably into a familiar style. Dan Bejar's albums as Destroyer had been yielding diminishing returns in recent years, and it had begun to seem like he was going to keep mining the same basic territory until everyone who once loved his quirky, urbane, complex pop grew bored of the stagnation. Instead, he's turned to an out-of-favor style from the past, swathing his songs in reverb-heavy lite-jazz and balearic pop atmospheres, recalling the crude synth presets and shimmering, plastic production of early 80s radio pop. It's a daring reinvention, and what initially might seem like a gimmick soon reveals itself, over multiple listens, as a brilliant aesthetic maneuver. Bejar's usually spiky voice is smoothed out to fit the glistening musical backdrops, and the album glides by so effortlessly that Bejar's characteristic wit has a chance to sneak up on the listener for once. The music is sad and sweet, and there's a lonely nostalgic feeling built into Bejar's trip to the musical past. Horns echo within the mix, surrounded with reverb to impart a feeling of distance, as though the trumpeter is miles away, intoning lonely notes into a void. Bejar is taking music often thought of as kitschy and dated and reconstructing it as haunting downer pop, revealing the loneliness and emptiness lurking behind the party gloss and disco gleam. Because of the subtlety of it all, and the initial impression of surface slickness, it's a real grower of an album that only parcels out its secrets slowly, gradually accumulating emotional depth and intensity until the kitschy surface style seems like the most natural possible way of capturing these dark, secret feelings.

[buy]

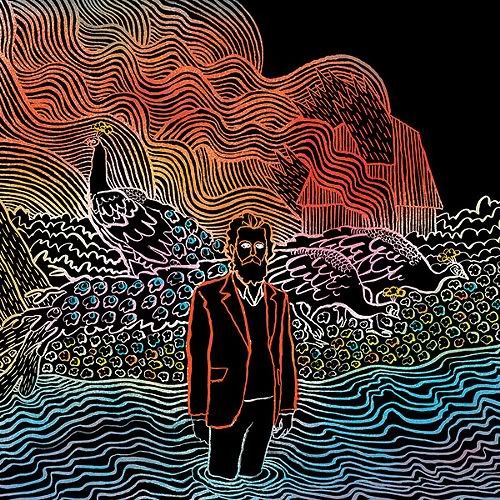

14. The Mountain Goats | All Eternals Deck (Merge)

14. The Mountain Goats | All Eternals Deck (Merge)

Few songwriters are as prolific or as dependable as John Darnielle, who has amassed a truly staggering catalogue of songs over the past twenty-plus years, ranging from the lo-fi solo boombox recordings of his early years to the much more polished full band releases he's turned to since the start of the 2000s.

All Eternals Deck is yet another gem from Darnielle, and as a consequence it'd be easy to overlook or underrate, to dismiss it as just one more solid release from an artist who's seldom less than enjoyable. In fact, this album, without being a big departure, is one of the best Mountain Goats albums in years, maybe even the apex of the years since Darnielle left his boombox behind. This is a varied album that showcases just how versatile Darnielle's seemingly simple sensibility is. He can follow up the aggressive, angry rocker "Estate Sale Sign" with the understated ballad "Age of Kings," and both sound totally in character. Later, on the album's most obvious stunner, Darnielle's scratchy croak strains and cries above a bed of barbershop backing vocals on the lovely, melancholy "High Hawk Season." Darnielle's storytelling is also as fantastic as ever, particularly on a pair of songs paying tribute to mother-and-daughter Hollywood icons. "The Autopsy Garland," about Judy Garland, seethes with subtle suggestions of exploitation and manipulation, while "Liza Forever Minnelli" somehow manages to be triumphant and melancholy all at once. The latter song repeatedly stresses that the narrator can "never get away," then climaxes with the clever line, "anyone here mentions 'Hotel California' dies before the first line clears his lips," an expression of frustration in defiance of easy clichés. Darnielle, thankfully, never deals in clichés except when he's subverting them, which is why his lyrics always feel so fresh, so lived-in and real, like sometimes enigmatic snippets of real lives.

[buy]

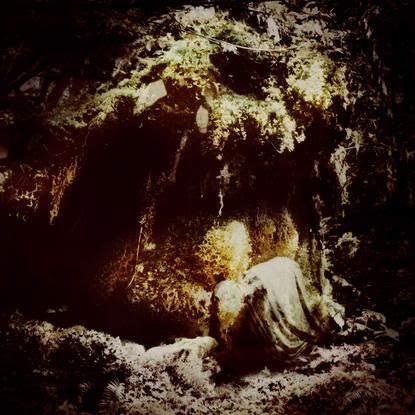

15. Corrupted | Garten der Unbewusstheit (Nostalgia Blackrain)

15. Corrupted | Garten der Unbewusstheit (Nostalgia Blackrain)

Japanese doom metal band Corrupted has always balanced their intense, despairing metal with restraint and musicality; their epic 1999 album

Llenandose de Gusanos opened with almost 20 minutes of delicate piano before the guitars and guttural growls finally appeared. Their newest album takes that approach even further, allowing bursts of bleak metal furor to emerge organically from the wasted sonic landscape that the band patiently builds. The first track, "Garten," opens with plucked electric guitar notes that reverberate into near-silence before each new sound appears. From this spartan foundation, the band gradually creates a somber atmosphere that seems to be marching towards a stormy musical catharsis, especially when the low, raspy whispers of vocalist Taiki add to the darker shadings of this plodding death-crawl. The explosion, when it comes, is somewhat contained, though, controlled rather than chaotic, a focused expression of emotional ruin that's all the more affecting for its precision and its intimate connection to the slow-building progression that preceded it. It takes almost 20 minutes for this half-hour song to truly kick into gear, and the patience of this build-up is excrutiating and thrilling in equal measure. Then, after a brief acoustic palette cleanser, the equally epic final track leans more heavily towards sustained scorched-earth metal rage.

[buy]

16. David Thomas Broughton | Outbreeding (Brainlove)

16. David Thomas Broughton | Outbreeding (Brainlove)

David Thomas Broughton's 2005 debut album

The Complete Guide to Insufficiency was a late discovery for me, or else its haunting choral minimalism would surely have ranked among my favorite albums of the 2000s when I compiled my best-of-the-decade list. This year, after a number of EPs and minor releases, Broughton finally returns with a proper follow-up.

Outbreeding is a very different record from Broughton's debut, replacing that album's lengthy quasi-improvisations with a series of short, lushly arranged folk-rock tunes, slotting Broughton's mannered vocals and wry wordplay into much fuller arrangements than those found on the sparse

Complete Guide. There's an arch, aloof quality to Broughton's carefully enunciated intonations, and he takes clear delight in drawing out certain syllables, rolling his R's and stretching vowels into eccentric shapes. He clearly loves saying "fuck" so much that it comes out like "fook;" he savors the shapes of words until they're stretched out of joint. This quirky vocal style draws attention to the subtle cleverness of the lyrics, like the sprightly punning of "Ain't Got No Sole" or the tongue-twisting eloquence of these lines from "Staying True": "my body is so crap at staying true/ to my will and the way I'd like to be/ my father's fist is a brick in my heart." Broughton has refrained from simply repeating himself. With a bonafide masterpiece of droning minimalist folk under his belt he now turns his attention to wry pub pop, the obvious irony in his tone not disguising the equally obvious emotion underpinning his elliptical musings.

[buy]

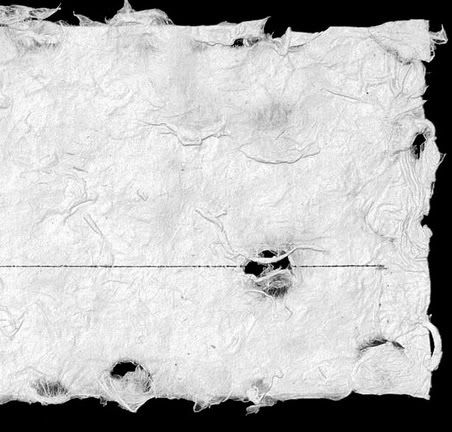

17. Tim Hecker | Ravedeath, 1972 (Kranky)

17. Tim Hecker | Ravedeath, 1972 (Kranky)

The title of Tim Hecker's latest album suggests nostalgia, or maybe regret, and the dates on several of the track titles follow suit, but the music itself is anything but backward-looking or nostalgic. The dates here suggest the passage of time and the continual presence of the past — the album cover is a photo of the first of MIT's annual "piano drop" events, from 1972 — because the album is about degeneration and decay, the loss of quality that happens over time. Hecker simply speeds up the process. Working entirely from a day's worth of church organ recordings, Hecker has subjected his source material to rigorous and violent processes that transform the organ drones into multilayered digital textures, creeping ambient soundscapes, the music trapped in a tug of war between harshness and beauty. Sometimes these electronic drones subside to a whispery bed of static, while at other times the mix is hot and distorted, artifacts of digital compression punching holes in the underlying organ notes. It's intense and hauntingly beautiful, music in which the specters of loss and destruction are constantly present.

[buy]

18. Michael Pisaro | Hearing Metal 2-3 (Gravity Wave)

18. Michael Pisaro | Hearing Metal 2-3 (Gravity Wave)

Michael Pisaro's

Hearing Metal series continued this year with a pair of new discs that both work on their own merits as individual recordings and as parts of a larger whole (which must also include 2009's

Hearing Metal 1). These pieces, all of them made in close collaboration with Pisaro's frequent interpreter, the percussionist Greg Stuart, are examinations of texture and fine grain. At moderate volumes, these are gorgeous drones, with subtle shifts between layers of bowed or scraped percussion, field recordings, and electronic sine tones. At higher volumes, the real complexity and density of this music becomes apparent, and the effect can be frankly overwhelming, even suffocating, as Pisaro and Stuart create these ringing, glistening waves of sound, like the neverending aftershock of a tremendous gong being struck.

Hearing Metal 2 is divided into three tracks, but it's dominated by the central 40-minute movement which consists of cascading metallic percussion reverberations. This piece is balanced between the harshness and clamor of the sounds and the serenity and suspension that are always such a big part of Pisaro's work. The album is bookended by two shorter pieces, the first an 18-minute movement that mingles field recordings of birdsong and other natural sounds with electronic tones, and the second a miniature that briefly returns to the birds chirping as a spacious, organic respite after the dense, unearthly drones of the monolithic second track.

Hearing Metal 3 is a single 45-minute piece, but somehow it feels more segmented, less monolithic, than its predecessor. The palette is again bowed percussion and sine tones, and for the first half of the piece, the sound ebbs and flows subtly, Pisaro pitching his electronics to blend almost seamlessly with the glistening metallic drones Stuart excites from his cymbals. At around 20 minutes in, sustained organ-like electronic tones take on a more pronounced presence, leading into a sudden eruption of tinkling, chiming cymbal hits from Stuart, with brushes dancing against metal like rainfall on a roof, producing a stream of particle-like sounds that break up the singularity and stability of the drone. The effect is hard to describe, but exhilarating, especially when heard as the climax of an unbroken listen to

Hearing Metal 2 and

Hearing Metal 3 together: it's a sudden release, a break in the constant suspense of bowed drones with nary a hint of more percussive sounds. From then on, the music becomes more granular, the long droning tones augmented and at times replaced entirely by hissing beds of static and tiny pitter-pattering droplets of percussive sound.

[buy]

19. Gang Gang Dance | Eye Contact (4AD)

19. Gang Gang Dance | Eye Contact (4AD)

Gang Gang Dance's latest album takes its time kicking into gear, opening with the slow-burning, 11-minute "Glass Jar," which builds from a low-key synth drone into a pulsing, structurally complex electro-pop dance tune. It's hard to remember at this point that Gang Gang Dance once dealt in weird, semi-improvised jams where bursts of rock or fractured pop burst organically and sporadically from the surrounding thickets of abstract noise and psychedelic formlessness. The opener of

Eye Contact provides a reminder of those origins, building only gradually towards the polished, quirky avant-pop that is the band's current specialty. This is the band's slickest and cleanest record, continuing the trajectory they've been on ever since 2005's

God's Money and 2008's

Saint Dymphna (still probably their best record, by just a slight margin). The sound is airy and percussively throbbing, with singer Lizzie Bougatsos cooing and sighing over glistening 80s pop homages ("Chinese High"), ethnic music mash-ups ("Thru and Thru"), and dancefloor bangers ("MindKilla") alike. Despite this sonic diversity, the songs flow seamlessly together in a unified suite, joined together at times by shorter instrumental sections that again recall the band's jammier early days.

[buy]

20. PJ Harvey | Let England Shake (Island/Vagrant)

20. PJ Harvey | Let England Shake (Island/Vagrant)

The always chameleonic PJ Harvey has never made the same album twice, and her latest work is yet another bold departure.

Let England Shake finds Harvey in a much poppier mode than ever before, her voice clear and direct, surrounded by elegant arrangements of horns and keyboards, with male backing vocals joining her on many songs. This is a set of accessible, densely arranged pop/rock songs, and they're fantastic songs, too. More importantly, Harvey hasn't sacrificed the grit and the anger that have always made her such a thrilling artist. Despite the album's more straightforward sound and the trilling, even pretty quality of Harvey's singing, this is music that's seething with righteous outrage: the theme is war, and Harvey's lyrics trace the waste and cruelty of warfare and bloodshed on one track after another. Her voice, though tending towards upper-register beauty, still drips with bile and barely contained sarcasm. The album's narrative is grounded in the wartime experiences of Europe, particularly England during World War I, but Harvey's clearly got one eye on the present as well, and her WWI parables resonate with contemporary conflicts. That she's crafted such a compulsively listenable and enjoyable album around such bitterness and anger only makes her accomplishment that much more impressive.

[buy]

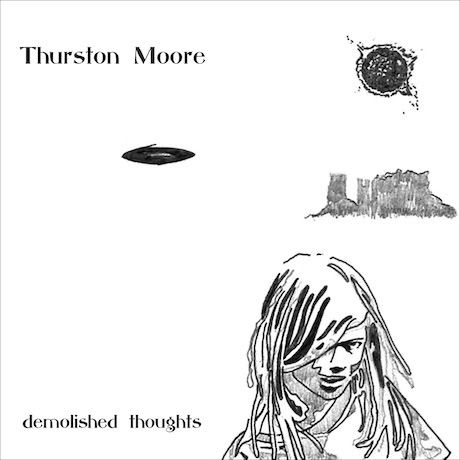

21. Thurston Moore | Demolished Thoughts (Matador)

Demolished Thoughts

21. Thurston Moore | Demolished Thoughts (Matador)

Demolished Thoughts is that rare Sonic Youth side project/solo album that actually lives up to the legendary status of the band itself. SY frontman Thurston Moore, assisted by the crisp, clean production of Beck Hansen, has crafted an album that's both distinct from his parent band and a fantastic statement in itself. The emphasis on acoustic guitars and elegant arrangements of strings gives the album a stripped-down chamber folk sound that's a perfect accompaniment to the gruff, straining quality of Moore's voice. The album isn't a total departure from Sonic Youth's legacy: tracks like "Circulation" and "Orchard Street" sound like an acoustic take on Sonic Youth, with Samara Lubelski's violin providing an accelerating whine that, on an electric SY track, would've been the forte of Moore's own jackhammering guitar. In fact, despite the acoustic folk instrumentation and Moore's often hushed delivery, these songs are often anything but laidback or relaxed. There's as much churning intensity in Moore's acoustic strumming as there is in his more familiar electric work, and many of the songs are as propulsive and full of jittery energy as the best SY tracks. But

Demolished Thoughts is probably better than anything that SY themselves have done in years; the new instrumentation and new band seems to have shaken Moore up and urged him on to new levels of brilliance.

[buy]

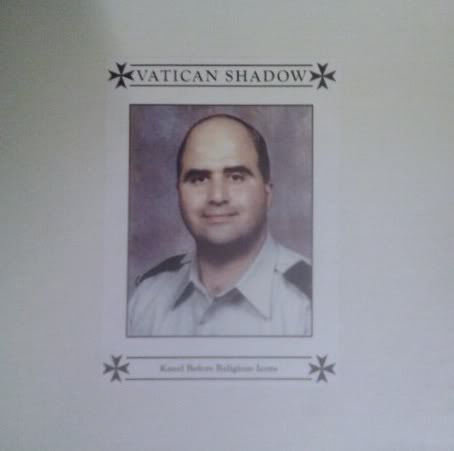

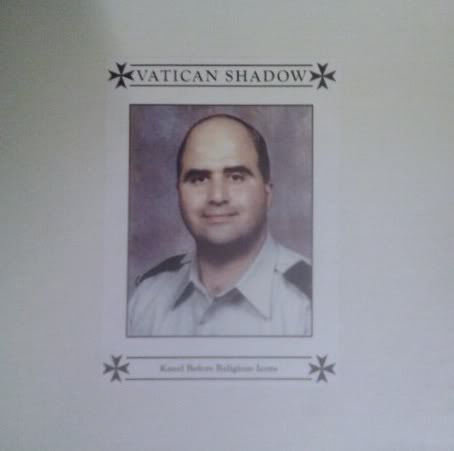

22. Vatican Shadow | Kneel Before Religious Icons (Hospital)

22. Vatican Shadow | Kneel Before Religious Icons (Hospital)

In the past year, Dom Fernow (of Prurient and Hospital Records) has unleashed a torrent of cassettes recorded under the alias Vatican Shadow. On these limited-edition tapes, Fernow eschews both the feedback-and-vocal noise of the bulk of his output and the weird, minimal synth confessionals of this year's Prurient full-length,

Bermuda Drain. Instead, Vatican Shadow is all about 80s tape noise culture, primitive power electronics and crude synth experiments. It's also some of the best music Fernow has made. The artwork and song titles of these releases make references to contemporary news stories from the War on Terror, a nod to the polemical politics of noise pioneers like Muslimgauze and the shock-value obsession with death and violence that run all through this scene. But the music itself betrays little hint of these obsessions, except in the way it sonically creates a mood of downbeat introspection. Fernow blends martial industrial beats with minimal, hauntingly beautiful synthesizer lines that wouldn't be out of place on a noise tape, a Tangerine Dream album, or a modern drone disc. The result is surprisingly powerful considering the simple elements. The tension between the pulsing, machine-like rhythms and the fragile beauty of the synths, which are sometimes crushed beneath the beats, and sometimes soar above them, provides an aural equivalent of the thematic emphasis on war and contemporary politics. This particular set, a box of four short tapes, is perhaps the best (and the most beat-heavy) of many Vatican Shadow releases from this year, but they're almost uniformly excellent, and thankfully they've all been released digitally to compensate for the scarcity of the physical releases.

[buy]

23. Sean McCann | The Capital (Aguirre)

The Capital

23. Sean McCann | The Capital (Aguirre)

The Capital is a rare LP release from Sean McCann, who generally unleashes his work as a string of limited cassette releases. This is a gorgeous work well deserving of the (slightly) increased profile the vinyl format has afforded him. There's a quasi-religious, ecstatic component to McCann's bubbly, liquid synth drones, with choirs of voices seeming to sing in exultation from deep within the mix, riding the ebbs and flows of his waves of sound. This is drone music of exceptional complexity and depth, with acoustic instruments and field recordings blended together with the sweeping synth drones to create a warm, even organic sound that's as inviting as it is beautiful.

[buy]

24. Pete Swanson | Man With Potential (Type)

24. Pete Swanson | Man With Potential (Type)

Pete Swanson's newest album is a pulsing, aggressive noise record that blends the industrial menace of his former band Yellow Swans with dancefloor techno and glitchy 90s IDM. It's a potent blend, and the album's six epic compositions churn with noisy waves of distortion weaving between the pounding techno beats, with bits and pieces of electronic detritus flying around the edges. On the closer, "Face the Music," the techno reference point is hidden, nearly erased by the volatile onslaught of digital noise; it feels, rather than sounds, like there's an actual techno track hidden somewhere in the mix, a ghostly subliminal presence that exists only as the faintest forward pulse hidden at the core of the dense sound. The opening track, "Misery Beat," is more direct in its rhythmic drive, and in between these two extremes Swanson explores various intersections between dance music, abstraction and noisy catharsis.

[buy]

25. Panda Bear | Tomboy (Paw Tracks)

25. Panda Bear | Tomboy (Paw Tracks)

Panda Bear's 2007 solo album

Person Pitch took the Animal Collective singer's distinctive voice and couched it in rhythmic loops that recalled the Beach Boys being taken apart and reassembled on the fly. It was a tough act to follow, made even more daunting by the flood of imitators who have in recent years colonized the sonic territory opened up by Panda Bear and Animal Collective. If the eagerly anticipated

Tomboy doesn't quite live up to its predecessor's high standard, it's still a fine album in its own right. More relaxed and dubbed-out than

Person Pitch, this disc ambles along on burbling loops with Noah Lennox's sweet voice crooning and echoing from deep within the mix. The album's sound, masterminded with the collaboration of Spacemen 3's Sonic Boom, is spartan and stripped down, never more so than on the aptly named "Drone," which is little more than a simple humming synth line with choral harmonies reverberating as though bouncing off the high walls of a cathedral. The sound is spiritual and often churchy, largely toning down the bouncy pop energy of

Person Pitch and the livelier Animal Collective tunes in favor of introspective minimalism. The album's seeming simplicity, though, is actually emotional immediacy, and the dense production sound, with its nods to dub's low end and the claustrophobic clamor of Phil Spector, only emphasizes the fragile beauty of the voice cutting through the darkness to deliver these soaring "surfers' hymns."

[buy]

26. Voder Deth Squad | 1 (Stunned)

26. Voder Deth Squad | 1 (Stunned)

This first collaboration between synthesizer artists M. Geddes Gengras and Jeremy Kelly is one of the year's very best tapes, a spacey and slow-moving dual synth drone that's utterly immersive and emotionally satisfying. The two artists are in a clear dialogue throughout, playing off of one another's sounds, layering swells of electronic noise over quasi-melodic shimmers. Over the course of the cassette's two half-hour sides, the music alternates between movements of glistening iciness, lush, distorted melodicism, and bleep-and-bloop spaciness. Best of all, there are very clearly two voices at work here, though it's impossible to separate the artists' contributions from one another; their separate lines intertwine seamlessly without erasing the impression of two ideas interacting in real time.

27. Wolves In the Throne Room | Celestial Lineage (Southern Lord)

27. Wolves In the Throne Room | Celestial Lineage (Southern Lord)

Brothers Nathan and Aaron Weaver conclude the black metal trilogy they started with their staggering 2007 album

Two Hunters, and its a worthy, appropriately apocalyptic conclusion. Wolves In the Throne Room have always blended their black metal sturm-und-drang with conventionally pretty female vocals (here, as on

Two Hunters, provided by Jessika Kenney), a droning experimental sensibility, and an interest in structure that allows them to alternate the more pummeling, blistering stretches (like the harrowing "Subterranean Initiation") with restrained and even beautiful moments. Sandwiched in between the slow-burn 12-minute opener "Thuja Magus Imperium" (which moves from serene Kenney vocals to room-clearing tumult) and the aforementioned "Subterranean Initiation" is a curious sound art miniature on which Isis vocalist Aaron Turner chants, accompanied by scraping metallic noises. Later, on the appropriately named "Woodland Cathedral," Kenney's voice soars and keens over pulsing waves of feedback and Kosmische synthesizer sweeps. The band continues to experiment with sounds and approaches that usually fall outside the black metal aesthetic, incorporating the repetitive minimalism of early 2000s post-rock and the hypnotic synth washes of Krautrock into their melancholic, desolate sound.

[buy]

28. Vladislav Delay Quartet | s/t (Raster-Noton)

28. Vladislav Delay Quartet | s/t (Raster-Noton)

Sasu Ripatti, who has been recording solo electronic music as Vladislav Delay for some time now, here tries something different by assembling a live band to play a largely acoustic set that sounds a bit like a jazz band doing dark ambient. Ripatti himself plays drums, Lucio Capece contributes howls and long whistling tones on soprano sax and bass clarinet, Derek Shirley drives the music along with throbbing double bass, and Mika Vainio adds the only electronic contributions. The music is dark and sinister, creeping along at a plodding pace like a movie monster inexorably pursuing its prey. Ripatti's percussion is largely sparse, providing a slow rhythmic underpinning with tinkling cymbals, while the other musicians craft grim soundscapes from electronic noise, bassy rumble and the eerie sounds of Capece's horns, sometimes processed and blurred, sometimes play acoustically with just his breath whistling through the instrument, not quite sounding a note. The entire album is great, but the clear highlight is the 12-minute "Santa Teresa," a foreboding death march that, I'd like to think, provides a tribute through its title and its haunting atmosphere to the fictional and violent Mexican city of Roberto Bolaño's epic novel

2666.

[buy]

29. Toshimaru Nakamura | Maruto (Erstwhile)

29. Toshimaru Nakamura | Maruto (Erstwhile)

Toshimaru Nakamura's music — made with the piercing, extreme frequencies generated by a mixing board with its inputs and outputs looped together — has always been challenging, but

Maruto is perhaps the first time that he's truly pushed the boundaries of his sound in a solo context. Nakamura's solo albums have generally been much more rhythmic and accessible than his collaborative improvisations, and perhaps because of this, his solo albums (the 2003 oddity

Side Guitar excepted) have never been as good or as enduring as his collaborations with musicians like Keith Rowe, Sachiko M, Ami Yoshida and others. He's often been thought of as a musician who needs another person to respond to in order for his talents to really shine.

Maruto proves that this is not true; entirely on his own, his music stripped down to its essential elements, Nakamura has made one of his best records. The first few minutes of the record instantly announce that this is something special, as stuttering electronic tones lurch drunkenly, leaving space in between for high-frequency fluttering. It's immediate and intriguing, nodding to the rhythmic foundation that often buttresses Nakamura's solo work, but offering a very unusual slant on those rhythms. Moreover, Nakamura soon lets this quasi-rhythm die out entirely, to be replaced by a spacious abstract field in which high- and low-register tones weave together. Sometimes, a bassy vibration, felt as much as heard, is cut by piercing high tones and some dirty fuzzy sounds that chop at the stasis of the underlying hum. Sometimes, sine waves flicker just at the upper fringes of hearing, a barely audible tingle in one's ears. The music seems simple, elemental in its juxtaposition of highs and lows at the opposing thresholds of the human hearing range, but close listening reveals a whole aural world of miniscule vibrations, hums, static and cycling electric buzzes.

[buy]

30. Akron/Family | S/T II: The Cosmic Birth and Journey of Shinju TNT (Dead Oceans)

30. Akron/Family | S/T II: The Cosmic Birth and Journey of Shinju TNT (Dead Oceans)

Akron/Family's latest, despite the typically twisty title, may be the band's best and most directly accessible release yet, an album of joyous psych/folk tunes where their sometimes ambling sound is honed to laser-beam precision. The exuberant opener "Silly Bears" owes more than a little to Animal Collective, but from there they stretch out in all sorts of directions. "Island" is a hushed campfire ballad with whispery vocals floating above a plodding beat until the last minute abruptly fills out into a shimmery climax. "So It Goes" is a stomping electric rocker with riffs rooted firmly in the garage, leading directly into the relentless hurtling rhythms and crooning vocal harmonies of "Another Sky." Elsewhere, the band alternates bursts of cacophonous psych-rock with infectious indie-pop on "Say What You Want To," offers up lilting acoustic lullabies like "Cast a Net," and generally has just tightened up their songwriting and playing in every way. It's a fantastic album that doesn't ditch the band's prior quirkiness and druggy experimentation so much as refine it, filtering it all into a diverse set that's far more focused than they've ever been before.

[buy]

31. Julia Holter | Tragedy (Leaving)

31. Julia Holter | Tragedy (Leaving)

On her debut full-length, Cal Arts composer/singer Julia Holter crafts a strange but nearly seamless blend of modern composition with quirky avant-pop. After an introductory overture that consists of industrial-electronic buzz, breathy horn whispers, a steam whistle and some operatic soloing, Holter launches into "Try To Make Yourself a Work of Art," which couches her vocals amidst clattering percussion and hammering, overtone-laden chords, before giving way to an ambient drone that leads directly into the next track. Holter adopts a number of approaches and styles throughout the album, never sitting still in any one mode for very long. The music is often abrasive and discordant, but Holter's equally capable of a serene, unearthly beauty very reminiscent of Julee Cruise's collaborations with David Lynch. She bridges these two modes with snatches of string composition, foreboding synthesizer washes,

musique concrète sound collages, and anything else she can think to throw in there. Curiously, the overall effect of the album is never schizophrenic or scattered, and Holter's sudden digressions never seem out of place. This is true even of the weirdest of them, like the minimal vocoder ballad "Goddess Eyes," which sounds like a radio pop tune distilled to its skeletal essence, a basic beat over which Holter layers her voice both processed and bare, with burbling synth tones gradually accumulating around her. Later, on "So Lillies," several minutes of augmented field recordings are eventually overlaid with a throbbing motorik beat and Holter's echoing vocals, for a low-budget Krautrock approximation. Holter's all over the place on this album, but what's really remarkable is that somehow she's managed to create a cohesive statement from all these fragments of styles and approaches.

[buy]

32. Shabazz Palaces | Black Up (Sub Pop)

32. Shabazz Palaces | Black Up (Sub Pop)

I'm always happy to admit it if I'm wrong, and I was very wrong about this album at first. It took a long time for the serpentine structures and bracing, staggering rhyme schemes of this experimental hip-hop outfit to sink in with me. If at first I found it simply impenetrable, I've still been compelled to revisit

Black Up over and over again until it opened up its delights to me. And it's packed with plenty of delights. The work of former Digable Planets MC Ishmael Butler and multi-instrumentalist Tendai Maraire,

Black Up is a dense and unusual hip-hop album, which is why it required some period of adjustment. Butler's raps are often just simplistic repeated chants, incantatory announcements intoned over woozy, drunken beats that seem to be stumbling over each other. At other times, the rapper delivers pattering, fast-paced verses packed with clever wordplay. The music is by turns jazzy, soulful, and discordant, often within a single track, and there's almost always a heavy, buzzing bass presence that allows the complex song structures to hang together. There's even room, on the record's back end, for guest appearances from female soul duo THEEsatisfaction, whose voices provide a contrast against Butler's nasal raps on a few tracks, especially the fractured lounge-jazz of "Endeavors For Never." This is bold, exciting music, all the more rewarding for the time it took me to get used to its intriguingly askew approach to hip-hop.

[buy]

33. Radu Malfatti/Keith Rowe | Φ (Erstwhile)

33. Radu Malfatti/Keith Rowe | Φ (Erstwhile)

This daunting triple-CD set represents the first duo encounter between two very different elder statesmen of modern electroacoustic music. Keith Rowe, the longtime tabletop guitarist for the legendary AMM, is a versatile musician who has, especially in the last decade or so, all but defined a certain strain of thoughtful, sonically varied improvisational music. Radu Malfatti is a trombonist who originally came from a background in jazz and European free improvisation but has, since the early 90s, become a minimalist composer whose work charts the extreme edges of silence and austerity. This album, which documents virtually the entirety of the music that the duo recorded during three days in a Vienna studio, is fascinating because it so tangibly captures the process of finding a common ground between different musical methodologies, different backgrounds and ideas. The musicians settled on four compositions — one piece by each of them, plus two pieces by other composers, so that Malfatti and Rowe each chose two compositions to play — as a prelude to the duo improvisation that takes up the entire third disc of the set. The compositions provide a way of exploring the players' aesthetics, finding the points of overlap (which exist mainly to the extent that Rowe can inhabit the patience and sparseness of Malfatti's musical world) and the useful tensions.

The disc opens, boldly, with a nearly silent piece by Malfatti's colleague Jürg Frey, which consists entirely of a handful of low tones, played in unison by the two musicians, scattered amidst a vast field of nothingness. Opening the album with this piece is a way of acknowledging up front the spartan, airless world of the Wandelweiser group of composers with which Malfatti is associated, and the remainder of the album is in a sense a series of movements away from this territory. On the subsequent pieces — a Rowe-chosen Cornelius Cardew composition, plus a recent Malfatti composition and a graphic score made by Rowe — the music still tends towards the minimal, but abandons that near-silent austerity. Static and radio hum from Rowe form an electronic bed for long rumbling tones and breathy exhalations from Malfatti, and occasionally the serenity is interrupted by piercing, squealing feedback or gritty, granular bursts of electric noise. The music remains low-key and gestural in spite of these outbursts. By choosing his abstract graphic score "Pollock '82" as the final composed piece of the session, Rowe sets the stage for the improvisation to follow. The improvised third disc doesn't depart very far from the sonic territory that precedes it, because part of this album's ideology is to blur the boundaries between improvisation and composition; it's all just music to these two players. And there's no question that the relaxed, seamless interplay of this improvisation is informed by the composed pieces — whether loosely notated or entirely abstract — from earlier in the session.

[buy]

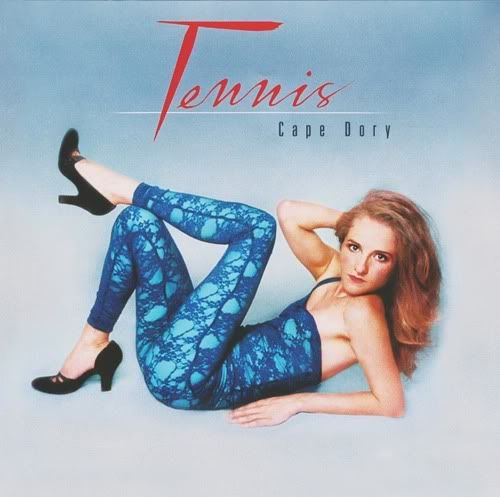

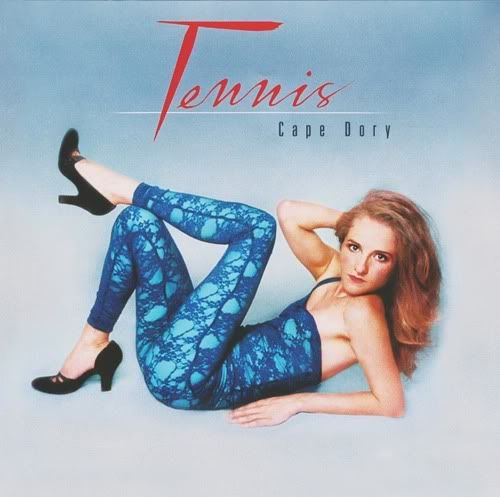

34. Tennis | Cape Dory (Fat Possum)

34. Tennis | Cape Dory (Fat Possum)

This was the first 2011 album I heard, way back in January, and I was instantly enthralled by its mid-winter evocation of a summery boat cruise. The husband-and-wife duo behind Tennis came up with these songs while on a long sailing trip, and upon returning to land they crafted this immaculate set of nautical pop. The result is nearly irresistible, all girl-group melodies and shimmery production that makes

Cape Dory seem less like a true summer album, more like a nostalgic backwards glimpse of summer, which I guess is why it was released in the winter and has returned to my regular rotation now that summer has come and gone. The songs are simple, direct and short, just perfect little slices of pop beauty, and at barely a half-hour long, the album never wears out its welcome. Instead, like the summer itself,

Cape Dory leaves one wanting more, wishing for just a little more sun and ocean spray, a little more of these sweet, warm, somehow a bit sad songs.

[buy]

35. Richard Youngs | Long White Cloud (Grapefruit)

35. Richard Youngs | Long White Cloud (Grapefruit)

Richard Youngs is a prolific and unpredictable musician whose work ranges from quirky folk and psychedelia to abstract improvisation and more, but my favorite of his many modes is the one he's in on

Long White Cloud. This is Youngs in his ethereal folksinger guise, singing plaintive melodies over delicate, chiming guitar picking or repetitive piano. After the understated elegance of the simple, pretty first two tracks, Youngs then stretches out for the mantra-like "Big Waves of an Actual Sea," on which he intones a droning chant over simple piano chords for a few minutes until suddenly introducing additional layers, echoing and superimposing his voice as the piano motif grows more complex as well. This is followed by the ritualistic "Rotor-Manga-Papa-Maru," on which Youngs keeps returning to the nonsense chant of the title over a grinding, circular guitar motif and a processed, growelly vocal sample that provides the song's bass pulse. The final track, "Mountains Into Outer Space," restates and reconfigures the melody and lyrics of the opening song, and it's the album's best piece and one of Youngs' very best songs. For nearly nine minutes, a blipping, skipping guitar pattern propels Youngs' soaring voice into the stratosphere, dripping with ache and reverb. It's a haunting tune, and

Long White Cloud as a whole is one of Youngs' best singer/songwriter albums, along with

Autumn Response and

Beyond the Valley of Ultrahits.

[buy]

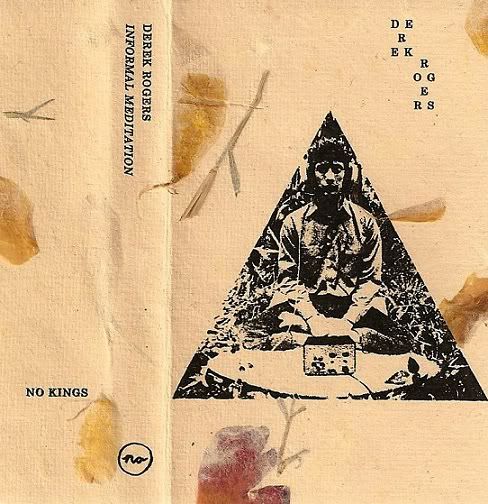

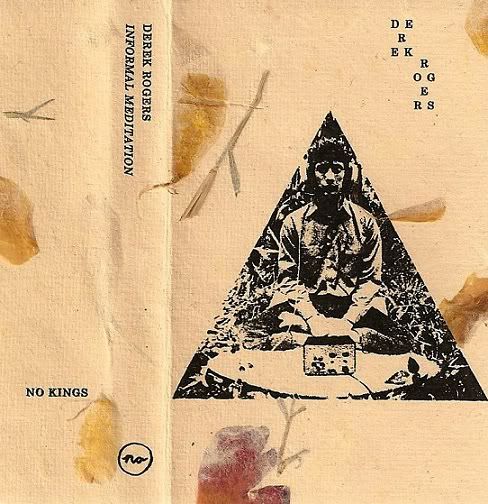

36. Derek Rogers | Informal Meditation (No Kings)

36. Derek Rogers | Informal Meditation (No Kings)

This cassette compiles a pair of half-hour live performances from 2010, both recorded in Texas using an iPhone. The compressed, slightly lo-fi sound is well suited to Rogers' rough, ragged take on ambient music, which contrasts melodic synth lines against grainy noise. The room atmosphere is a part of the recording, tangible in occasional snippets of crowd chatter, or felt more abstractly in the slightly distant, naturally reverby quality of the live recordings. This is deeply textured music, and unusually for an ambient/drone artist, Rogers' work is seldom static. Rogers is continually building a sense of forward momentum and musical development, as when the opening ten minutes of the first side-long track progress from low-key synth ambience to a tinkly music-box melody that then spirals out into a watery drone. Underneath the surface melodicism, Rogers grinds at the serene beauty of the synths with subterranean electronic crackle and industrial rhythms. There's a clear sense of forethought and spontaneous composition in these two pieces; they never seem to be meandering aimlessly or simply riding a repetitive drone, but are always building towards something, accumulating tension and structural complexity from Rogers' subtle shifts and layering.

37. Snowman | Absence (Dot Dash)

37. Snowman | Absence (Dot Dash)

There's something inherently interesting about an album that marks the demise of a band even as it comes out;

Absence, the third album of Australian art-rockers Snowman, arrives on the heels of the band's breakup, and it's a fitting final statement for this very unique band. Previous Snowman albums have been dense and aggresive, creating wild, careening music from fragments of post-hardcore and metal debris.

Absence is even weirder, achieving a ghostly, spectral beauty by stripping away many of the most obvious rock signifiers, leaving behind eerie electronic drones, trash-can rhythms, and ritualistic chanting. Words are seldom identifiable in the sea of processed, layered voices that drift through these songs; the lyrical content is not nearly as important as the sound, the rhythmic, repetitive chants which sometimes sound like choral rapture and sometimes like excerpts from some sinister pagan ritual.

[buy]

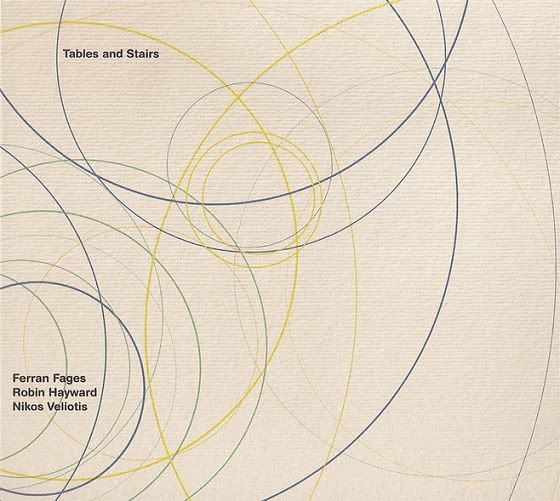

38. Ferran Fages/Robin Hayward/Nikos Veliotis | Tables and Stairs (Organized Music from Thessaloniki)

38. Ferran Fages/Robin Hayward/Nikos Veliotis | Tables and Stairs (Organized Music from Thessaloniki)

The tendency in avant-garde music is to emphasize constant innovation and change, but sometimes an improv record need not shatter boundaries to be really great. This trio set, a document of an intimate apartment concert in Greece, is a perfect example. The slow-moving textural improvisation here isn't ground-breaking, nor is it especially surprising coming from these musicians, but it is excellent, a concise thirty-minute exploration of glacial layers of sound. Over the course of this single piece, after the tranquil introductory minutes, the trio begins organizing sedimentary layers comprised of Ferran Fages' electronics, Nikos Veliotis' buzzing, sustained cello drones, and the subterranean rumble of Robin Hayward's tuba. It's great because the drone is anything but monolithic, and close listening reveals the shifting tectonic plates within, as the instrumentalists weave their long tones around one another. This intense droney segment is bookended by spacious scrape-and-hum build-up at the beginning, and a serene coda in which Fages' sine waves slowly pulse atop a gentle bed of little rumbles and the occasional fluttery moan from Hayward's tuba. This is a low-key but surprisingly dynamic disc, and a really enjoyable one.

[buy]

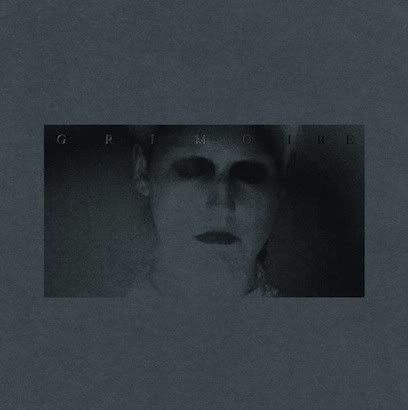

39. Kreng | Grimoire (Miasmah)

Grimoire

39. Kreng | Grimoire (Miasmah)

Grimoire is the second album from Belgian composer Pepijn Caudron, who specializes in bleak, creepy soundscapes that are balanced between modern composition and dark ambient electronics. Caudron arranges clusters of minor-key string crescendos with bits of piano, discordant processed horn blurts, bassy electronic drones, sampled voices and snatches of operatic singing. The music is nerve-wracking and intense, placing one continually on edge as its strained strings seem like a prelude to murder, madness and horror. On "Wrak," the tension-building rhythmic scrape of the strings soon gives way to a chaotic, tumultuous pile-up of noisy percussion, chattering voices, and horns that seem to be screaming in anguish. Caudron's music alternates between such intentionally ugly dissonance and stretches of eerie beauty that are no less unsettling. (Thanks are due to

Carson Lund for making me aware of this great album in time for it to make this list. He compared it to an aural horror film, and that's very apt indeed.)

[buy]

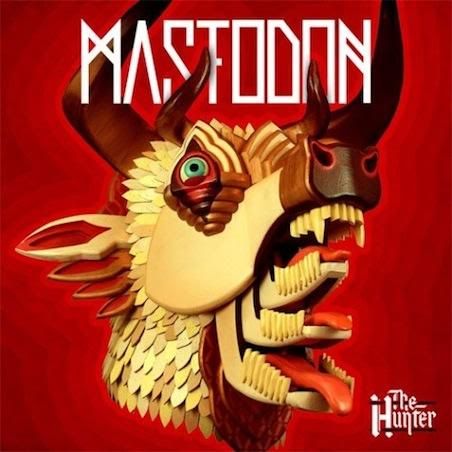

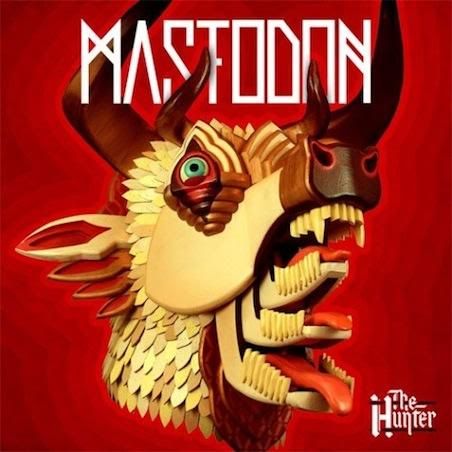

40. Mastodon | The Hunter (Roadrunner)

40. Mastodon | The Hunter (Roadrunner)

Ever since their debut album

Remission, Mastodon's sound has been steadily evolving from the heavy old-school metal of that debut towards an increasingly complex, proggy and melodic sound. They've become more accessible without compromising their intensity in the least, ratcheting up the technical and structural complexity of their music even as their melodies have become more forceful, their guitar leads more harmonic, the vocal balance between guttural howls and layered harmonies tipping more and more toward the latter.

The Hunter, their fifth album, continues that evolution, delivering one compact, punchy metal assault after another: they manage to condense prog metal bombast into three-minute radio-ready song lengths, complete with choruses that are both melodically direct and immensely satisfying. It's by far their most accessible and straightforward album, even poppy at times — they even paraphrase the Beatles on the swampy, psychedelic title track — but that doesn't mean it's a betrayal. The band's manic virtuosity doesn't seem the least bit constrained by the shorter track lengths or emphasis on melodicism. Instead, they've simply focused their talents to make one of the best mainstream rock albums in recent memory.

[buy]

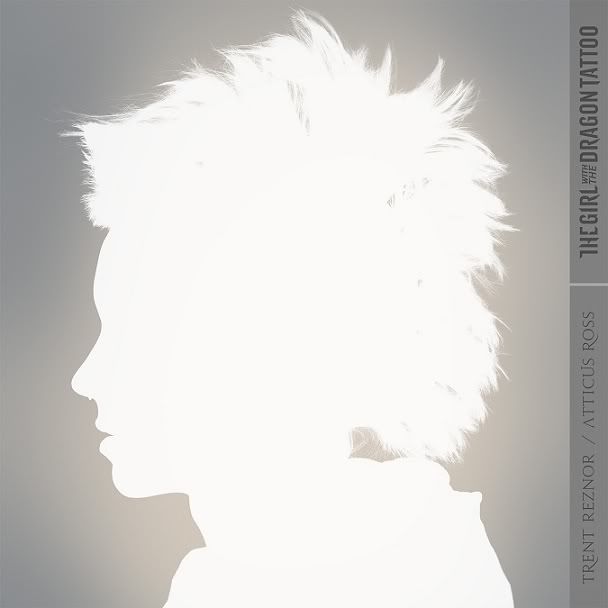

41. Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross | The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (Null Corporation)

41. Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross | The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (Null Corporation)

After last year's moody, effective (and Oscar-winning) score for David Fincher's

The Social Network, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross return with another score for another Fincher picture, and it's nearly as good as their last collaboration. The album is framed by proper songs — an aggressive, nasty cover of Led Zeppelin's "Immigrant Song" with Karen O of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs on vocals, and a Bryan Ferry cover by How To Destroy Angels, Reznor's band with his wife Mariqueen Maandig — but in between these tracks Reznor and Ross stick to the territory of minimal, downtempo ambience. Sprawling out over three hours, the score traffics in the same gloomy late-night atmospherics and ambient/industrial dread as

The Social Network, maintaining a near-constant mood of barely contained tension in its electronic soundscapes and minimal rhythmic skeleton. The music sometimes hovers on the threshold of audibility, just a subtle bass pulse, while at other times the duo create jittery, brittle rhythms with plastic-sounding guitars and percussion. Reznor's debt to the seminal British industrial band Coil has never been more obvious, and in a way Reznor's soundtrack work is a worthy tribute to Coil's unreleased and eerie score for Clive Barker's

Hellraiser. But Reznor and Ross are also expanding on their influences, making music that's both perfect mood-building accompaniment to cinematic images and a compelling listen on its own merits.

[buy]

42. The Weeknd | House of Balloons (self-released)

42. The Weeknd | House of Balloons (self-released)

Although the Weeknd's first mixtape, self-released for free on the Internet, undoubtedly benefitted from all the hype and mystery surrounding its release, the music here holds up well enough that it doesn't need the hype. Abel Tesfaye's high, slightly eerie croon, often tweaked or doubled, drifts hauntingly above the dank production on this suite of atmospheric R&B tunes. Tesfaye's lyrics often have a skeevy, seamy edge to them, lyrically tracing the boundaries of a world of late-night debauchery, drugs and alcohol haze, grinding and fucking in the club, then forgetting most of it the next morning. These songs deliberately erase distinctions of good or bad taste, while the moody production wraps comfortingly around Tesfaye's voice, which often seems to come, caked in reverb, from somewhere far away, his crude and crass words swathed in the darkness of a moonless night. The songs are often catchy, balancing pop-radio-ready synthesizer sheen with Tesfaye's blunt come-ons, so that the album's depiction of blank-eyed dionysian excess is made strangely appealing and even beautiful.

[download]

43. Earn | Performance (Ekhein)

43. Earn | Performance (Ekhein)

As the title of this 35-minute tape makes clear, each side is a live performance, recorded during 2009 and 2010. The generic title suggests that Matt Sullivan, the artist behind Earn, means for us to think in a broad way about what it means to perform music for an audience, and what it means to present a document of that performance as a recording. This meta-introspection becomes especially clear on the B-side, a 2010 recording from St. Louis, on which Sullivan's fuzzy, layered drones are infiltrated by the voices of people in the audience, chatting while the drone pours over them. The effect, though an accidental byproduct of an amateur recording in a live venue, is stunning: the voices are mostly swallowed by the music, their words obscured and clipped by the waves of electronic noise. It's so perfect that it almost seems as though Sullivan has simply introduced some sampled found sound recordings into the mix. But that's part of what the album is about, embracing the roughness and loss of control that arise from live performance, incorporating interruptions and potential obstacles into the music as gracefully as possible. These considerations aside,

Performance is also just a great drone tape, subtle and textural, maintaining a careful balance between melody and abrasion.

[buy]

44. Lykke Li | Wounded Rhymes (Atlantic/LL)

44. Lykke Li | Wounded Rhymes (Atlantic/LL)

Swedish singer Lykke Li's second album is a vast improvement over her modest and intermittently enjoyable debut

Youth Novels. Not only has Li's voice matured, grown dark and tormented rather than cutesy, but her songcraft has improved as well, so that each track here is an efficient, emotionally charged pop nugget. Producer Björn Yttling, who also produced and co-wrote her debut, has swathed Li's songs in a sparse, dark production style that's perfectly suited to her confessional lyrics. Li's inclusion on the soundtracks to the second

Twilight movie and various CW teen dramas makes perfect sense, and her youthful earnestness and emotional honesty allow her to pull off lines like "sadness is my boyfriend" and make them feel like they come from a really deep, painful place.

Wounded Rhymes is as moody and changeable as a confused teen, equally prone to bursts of scattered psycho-sexual aggression — "like a shotgun/ needs an outcome/ I'm your prostitute/ you gon' get some," she sneers on "Get Some," making her come-on feel like a death threat — and diaristic moping, like the achingly pretty "Unrequited Love," on which Li's voice sobs above a quietly plucking backdrop.

[buy]

45. Tonstartssbandht | Hymn (Does Are)

45. Tonstartssbandht | Hymn (Does Are)

Tonstartssbandht is the lo-fi psych-rock duo of brothers Andy and Edwin White, and

Hymn is a tour cassette of previously unreleased odds and ends that manages to outdo their proper release from this year,

Now I Am Become.

Hymn collects bits and pieces recorded from 2009-2011, showcasing several different sides of the band's eclectic musical personality. "Susie" and "Jessie" are sludgy, muddy psych-rock jams, leaning heavy on the phaser pedal, with reverbed vocals echoing out over the underlying groove. Despite the lo-fi sound, the band's bright, energetic sense of melody shines through as the two brothers chant and croon in unison, their voices blending together. Voices are very important to this band, and the rest of the tape puts the emphasis squarely on exuberant vocals. This is where Tonstartssbandht really shines: "Hymn Eola" and "Hymn Our Garden" are solo tracks by each of the brothers, with the former affecting a blurry choral beauty and the latter delivering a much more structured dubby ambient pop tune. "New Black Fever," on which the band builds a whole new epic track around a Horace Andy cover, submerges the underlying reggae groove beneath waves of distortion-laden guitar soloing, with typically lovely vocal harmonies. This tape may just be a collection of leftovers thrown together for a tour, but it never feels like these songs are tossed-off or inconsequential. In fact, they're emotionally loaded and hauntingly pretty, contrasting the duo's layered, Animal Collective-like harmonies against the distorted guitars and swampy production sound.

[buy]

46. Frieder Butzmann | Wie Zeit Vergeht (Pan)

46. Frieder Butzmann | Wie Zeit Vergeht (Pan)

Frieder Butzmann is not a particularly well-known figure in the US, even by the standards of the avant-garde electronic music he's been making since the 70s, but he's apparently something of a legend in his home country of Germany. Based on this new LP, on which Butzmann combines processed and chopped-up samples of Karlheinz Stockhausen's voice with his own frenetically collaged electronic studies, it's not hard to see why he's earned such respect.

Wie Zeit Vergeht is an intense and frantic record that leaps spastically from one idea to the next; sometimes Butzmann's electronics form a deep, churning low-register drone, while at other times sizzling electronic tones skip and splutter like someone's rapidly whipping a radio dial back and forth. Stockhausen's voice shows up periodically, sometimes modulated until he almost seems to be singing, sometimes looped and chopped into rhythmic beats, sometimes manipulated until it seems like just one more element in the chaotic electronic stew. Maybe it's just that I don't understand the language, but Butzmann seems to be using the voice musically, as a sound source rather than for its textual content, which might be a wry way of saying that all musical touchstones, no matter how important or seemingly serious, can and will eventually be incorporated into the music of later generations. Thus Stockhausen's voice, if not exactly his ideas, finds a new place, a new musical life, within the context of Butzmann's often-goofy, always engrossing synthesizer collages.

[buy]

47. Resplendent | Despite the Gate No Mansion (self-released)

This latest album from the former frontman of the great (and sadly underrated) avant-rock trio the Fire Show has not gotten much attention this year — not surprising considering that Michael Lenzi has "released" his first recording in six years by quietly sending out free CD copies to anyone who happens to be on his e-mail list and

asks him for one. After the breakup of his former band, who quit right after releasing their defining masterpiece

Saint the Fire Show, Lenzi released a series of uneven but exciting solo EPs that were similarly low-profile, then quietly returned to obscurity. His sudden re-emergence might suggest a renewed interest in music or simply one more blip in a musical career that's too often slid under the radar, but either way,

Despite the Gate No Mansion is another fascinating offering from this idiosyncratic artist. The album opens with a few seconds of blistering white noise clamor, a palette cleanser and room-clearer before he's even begun, and from there Lenzi offers up a series of puzzling, jagged bedroom recordings with his off-kilter voice spitting out streams of wordy lyrics over crude electronic beats, trashy distortion-laden noise, and sampled voices stretched out into wordless hums. At times, he's more lyrically direct and earnest than he's ever been before, while at others he returns to the dictionary-trawling obliqueness of the Fire Show. This is a rough and obviously homemade album, with all the stitches and unsanded edges still showing. As with his previous solo work, not everything's a gem, but the looseness is part of the record's charm, and when he hits on something good, it's

really good. Highlights include the skipping-CD beat and painfully earnest vocal of "East Jesus," and the broken-synth sputtering and chanted insistence of "Kill That Fucking Lion." He saves the best for last, though, with the gorgeous "Soul Go Home," which opens a capella — recalling the daring vocal virtuosity of the Fire Show's brilliant "The Making of Dead Hollow" — then adds minimal horns, synth drones, and clipped vocal samples to build an affecting, sonically inventive closing lullaby.

[request]

48. Das Racist | Relax (Greedhead Music)

48. Das Racist | Relax (Greedhead Music)

Following up on the two free Internet mixtapes they released last year, Das Racist has now finally assembled their first proper, commercially available album. They seem very aware of the fact that this is their big moment, and they've crafted a tight, focused album that's very different in feel from the sprawling, goofy mixtapes. Though they recycle a few tracks from those mixes, there's nothing here quite like the utter ridiculousness of their breakthrough is-this-awful-or-brilliant viral single "Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell." Instead, much of the album is downright accessible and poppy, and tracks like "Girl" represent their seemingly earnest stab at a catchy techno-pop hit. Even there, though, the track is spiked with weirdly pitched-up Autotune vocal samples squealing piercingly in the background, suggesting that they can never quite play it

entirely straight. Indeed, though the group's most obvious Internet-humor moments have been trimmed away for this album, they're still incessantly referential, creating a postmodern collage where all of pop culture dances through their lyrics. Coupled with the multicultural edge of their music, they're pretty much the perfect hip-hop outfit to represent meme culture, except that they're genuinely